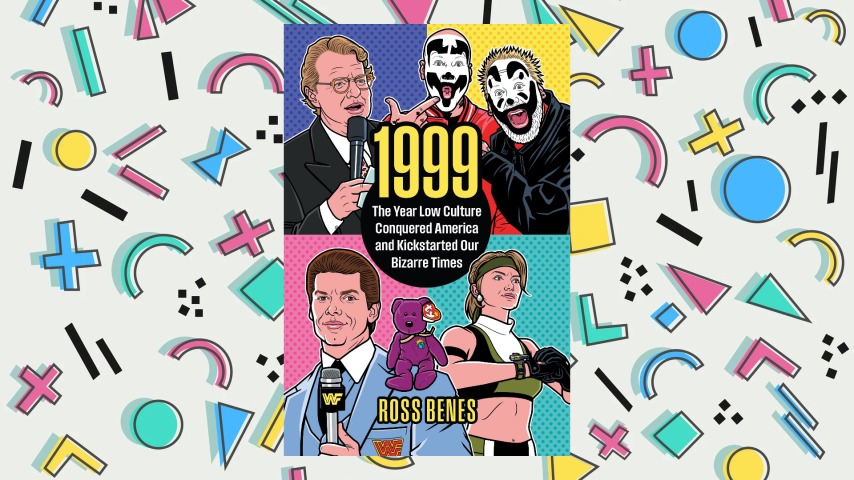

Author and journalist Ross Benes has a theory about how we ended up in our particularly strange modern world: It all started with the low culture boom of 1999. That was the year reality TV exploded, Woodstock ’99 somehow turned out even worse than the mud-flinging disaster of Woodstock ’94, and exploitative daytime talk shows like Jerry Springer rose to prominence. In his new book, 1999: The Year Low Culture Conquered America And Kickstarted Our Bizarre Times (out April 22 via University Press Of Kansas), Benes examines those moments and explores their impacts on the present day.

In this exclusive excerpt, Benes explains why reality TV became so prominent in the late ’90s and how the lines between it and actual reality have become increasingly blurred.

If you watch a fair amount of TV, you’ve seen housewives flipping over tables, pregnant teen moms fighting their boyfriends, dating show contestants spitting on each other, beach bums getting punched in the face, and long-bearded hunters driving their family members nuts. Although our collective TV viewing is fractured to an extent that largely prohibits shared pop cultural moments outside sports, many, if not most, consumers still recognize a Kardashian/Jenner viral post, The Bachelor rose ceremony, Big Brother espionage, Queer Eye makeover, Shark Tank business pitch, and Survivor challenge. This is because in the late 1990s and early 2000s, reality TV exploded. Since then, its presence, on our screens and in our lives, keeps expanding.

Mid-1990s government deregulations contributed to reality TV’s rise. FCC rules used to prevent the original broadcast networks (ABC, NBC, CBS) from syndicating programs they produced and limit the number of network-produced shows aired per week. Essentially, TV networks couldn’t control the rights to their primetime shows.

Once these rules were eliminated, TV networks could profit from syndicating their programming and were free of restrictions that limited content production. This contributed to TV networks cutting costs, reducing their reliance on union labor, and producing more reality shows.

Throughout the 1990s, reality shows were a cable hit on MTV. After MTV and CBS became sister stations, CBS brought reality to broadcast TV in a big way. Within two years of the merger, CBS rolled out three of reality’s most successful franchises—Big Brother, The Amazing Race, and Survivor. When Matt Damon said, “I always thought it better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody” in the December 1999 movie The Talented Mr. Ripley, his statement could have applied to many TV characters.

Viacom and CBS went all-in on reality because doing so was cheap, effective, and fit in with the company’s efforts to reduce production costs. Its executives watched MTV with the sound off because doing so “stripped away the music, which MTV does not own” and left “the process of blending the images, the promos, and the ads into precisely the right cocktail of programming, which is the thing that does belong to MTV,” reported the New Yorker. It pioneered the use of permalancers, which gave it fulltime laborers without having to provide benefits. Its cable stations relied heavily on young employees working big hours for little pay.

The strategy paid off. In the fall of 2000, more than fifty million Americans watched Richard Hatch walk around naked on a secluded island and out-scheme his fellow contestants to win Survivor’s first season. Only the Super Bowl received more US television viewers. Reality and unscripted shows were taking off elsewhere. ABC launched Who Wants to Be a Millionaire in the summer of 1999. Millionaire’s executive producer was hired “to find a show we could make at half the cost” of a scripted program. “Then the shows started getting these massive ratings.” Millionaire became the most-watched TV show that year, commanding gigantic ratings even when ABC aired it three times a week in primetime. On a typical weeknight showing, more than a quarter of TVs were tuned to Regis Philbin making contestants squirm in the hot seat.

In the following years, Simon Cowell’s brutal assessments of untalented singers, Paula Abdul’s charming encouragements, and Randy Jackson’s words of wisdom turned American Idol into a cash cow that’s still running and being imitated. Before he became one of America’s most popular political commentators, Joe Rogan challenged people to eat maggots and dunk themselves in tanks full of cow blood on Fear Factor. ESPN got in the mix by airing a show about streetballers who competed for a spot on the AND1 mixtape tour. The reality competition craze would reach pro wrestling with WWE Tough Enough shown on MTV. Another competition show, Making the Band, blended core MTV programming areas reality and music. The show produced acts like O-Town, whose first single Liquid Dreams sounded like the Backstreet Boys harmonizing about Saint Thomas Aquinas’s nocturnal emission pontifications.

The proliferation of reality shows helped popularize the concept that you didn’t need a traditional entertainment skill to succeed in its industry. Fame used to be, and in many cases still is, an unwanted byproduct inflicted on people who were talented at singing, acting, writing, directing, dancing, and so on. But for many of the largest entertainment stars, fame became the end goal. And you didn’t need talent to achieve it. In some ways, this wasn’t new. Throughout history there have always existed people who were famous for being famous. But these characters, often descendants of wealthy families or scandal subjects, were usually confined to tabloid pages and lifestyle rags. What changed in the late 1990s and early 2000s was the scale. No longer marginal, many of the world’s biggest stars were famous for being famous.

Some reality stars would transcend the genre. “New York, my city,” the narrator states in the opening sequence of a famed 2004 reality show. “Where the wheels of the global economy never stop turning. A concrete metropolis of unparalleled strength and purpose.” The narrator fancies himself as “the largest real estate developer in New York.” He describes how the mean streets hardened him, brags about his expensive lifestyle, shills for his brand, and portrays his millions in debt as personal assets. The show pits sixteen young entrepreneurs in a competition to become this man’s apprentice. The star and producer of the show is of course Donald Trump, president of the United States of America.

Trump was already a fixture in New York tabloids, softcore porn, pro wrestling, and real estate. But it was reality TV that made him an international star. In the United States alone, twenty million people tuned in weekly during the first season of The Apprentice.

The Apprentice was just one of many reality shows that found success leading up to the 2007 Hollywood writers strike. A deregulated syndication market, abysmal macroeconomic climate, and a labor stoppage by workers essential in creating scripted dramas created an environment where reality thrived. During the strike, American TV channels aired more than a hundred reality shows, many of them new franchises. The most influential reality show to debut then focused on the family of O. J. Simpson’s deceased lawyer, Robert Kardashian.

Keeping Up with the Kardashians would become synonymous with the reality genre. Like its predecessor The Osbournes, the show followed a marginally famous family doing ordinary things and reacting to contrived situations. “You are all often described as ‘famous for being famous,’” Barbara Walters said directly to several of the Kardashians and Jenners she was interviewing. “You don’t really act, you don’t sing, you don’t dance, you don’t have any—forgive me—any talent.” Khloe Kardashian nodded in agreement with Walters before replying, “But we’re still entertaining people.” Walters had a point, but the joke wasn’t on the Kardashian/Jenner family, it was on their critics.

Sure, the Kardashians don’t have the traditional showbiz talent that most people crave or work at. However, they know how to work supermarket tabloids, lifestyle publications, TV networks, radio personalities, streaming services, and social media better than anyone else. The family’s net worth is in the billions. Famous and influential people seek them out. When President Trump hosted Kim Kardashian in the White House, the photo op gave the appearance that America had finally amused itself to death. One reality star lobbied another reality star, who happened to be president. Given Trump’s erratic behavior, this meeting of the minds held policy-shaping potential. Making fun of the family’s braindead reality shows is easy, but they had the ear of the president, more fame and money than they knew what to do with, publicly advocated for causes they cared about, and seemed to be having fun in a world full of censorious bores.

The strike and Kardashian fever were followed by “the golden age of reality television, its second generation,” wrote Rax King in Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer. One character to emerge from this golden age is Theresa Caputo. With an aggressively Italian demeanor, brightly blond dye job, and fake nails, Caputo combines the hokey spirituality of Crossing Over with John Edward with the stylings of a vivacious suburban mom who has an acute sense of camp. In her shows Long Island Medium and Raising Spirits, Caputo parades around southeastern New York claiming to speak with dead people. In 1999, when a young Haley Joel Osment spoke to dead people in The Sixth Sense it was understood to be fiction. But when Caputo made outrageous claims to strangers in supermarkets, gyms, and autobody shops about their deceased loved ones, TLC and Lifetime portrayed her as a genuine communicator with the dead. As long as somebody in the selectively edited footage indicated that one of her various, and often conflicting, statements was vaguely familiar to their own situation, Caputo was shown as the real deal. Long Island Medium blurred the line between reality and unreality while insisting that its make believe stories were truth. These shows were asinine but entertaining.

The reality genre can be enjoyed with an understanding that the end product is engineered. This resembles pro wrestling fans who know matches are scripted but enjoy the meathead soap opera anyway. Wrestling ratings grew after the WWE acknowledged its matches were scripted. Fans enjoyed dissecting what was staged and authentic, how what occurred outside the ring informed what happened within it. A similar shift occurred within reality TV.

When news of an affair between Vanderpump Rules cast members broke before the episode about it aired, the show blended offscreen and onscreen accounts of a story that viewers were already aware of. The show stopped pretending to be the authoritative source for what transpired in its stars’ lives. When former cast members filed lawsuits against the show’s stars and paparazzi interrupted filming, Vanderpump producers didn’t ignore these controversies. They incorporated them into the show. A multiverse of podcasts and TikTokers debated which controversies genuinely affected the show’s stars and which were put on Bravo producers, which only generated more fan interest. “The collapse between show and reality catapulted the series into better ratings than it’s ever had before,” Vulture reported. “The real world was not a spoiler. It was a promotion.” This development isn’t surprising when the oval office functions as a reality program.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.