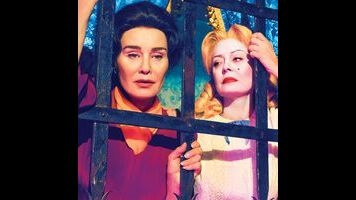

And that’s all before you get to the leading, feuding ladies. This ain’t Lange’s first time at the Ryan Murphy rodeo, and the gusto that’s often made her the only watchable part of American Horror Story is on full display here, along with the depth of feeling that garnered her a pair of Emmys in those shallower roles. Sarandon’s the newcomer, but her brassy take on Davis makes her feel right at home in the Murphyverse, whether she’s confessing her loneliness to Baby Jane director Robert Aldrich (Alfred Molina), sparring with her co-star or her daughter (Kiernan Shipka as B.D. Merrill), or casually mixing a martini while on the phone with Olivia De Havilland (Catherine Zeta-Jones).

Casually Mixing A Martini While On The Phone With Olivia De Havilland would make an excellent alternative subtitle for this installment of Feud. (Equally fitting: Mid-Atlantic Accents: The TV Show.) Aesthetically, the five episodes screened for critics are wall-to-wall glamour, composed of cavernous studio offices, on-set intrigue, and bathroom ice chests stocked with vodka. The Hollywood publicity machine has always masked dysfunction in stardust—in Feud, the dysfunction and the stardust go hand in hand, and no one’s trying to make you look at one instead of the other. Bette and Joan are set at odds by their decorating styles (Davis: high-class rustic; Crawford: plastic on the furniture) and chosen liquors (Crawford prefers the clear stuff to Davis’ browns) as much as their differing opinions and philosophies. Actors, directors, studio heads like Jack Warner (Stanley Tucci, a hoot), and trade reporters like Hedda Hopper (Judy Davis, doubly so): All are in the business of spinning fables, and the sheer degree of artifice on display in Feud is fascinating.

And below that most superficial of surfaces, there’s critique of Tinsel Town ageism, sexism, and homophobia, the sort of “science fiction but in the past” material that was Mad Men’s stock in trade. (Echoes of that previous show abound, but not even Don Draper could make a highball and a cigarette look as sexy and satisfying as, well, practically everyone on Feud.) Subtext is an Achilles’ heel that The People V. O.J. Simpson finally healed for Murphy, and though Bette And Joan doesn’t represent a full recovery, it lands some clever jabs at the staus quo through depictions of the stars’ insecurities and beauty regimens, one conspicuously and consciously lifted from Mommie Dearest, the previous gold standard for dismantling Crawford’s public persona. But just as it equates the stardust and the dysfunction, Feud doesn’t attempt a full salvage job on Crawford—and Lange’s tenacious performance wouldn’t let it, either. Her Joan gets to be a more sympathetic figure than Faye Dunaway’s, prone to rage, envy, and pettiness, but also shown to be living in soul-crushing isolation (scenes set in her home are shot to emphasize its loneliness) near the end of a career and a life that would twist the humanity out of the sturdiest of souls. Lange’s Joan is a large, fearsome presence, but she’s not the monster in cold cream screaming at Christine Crawford about proper garment care.

The pre-caricatured nature of all parties involved helps Feud sidestep characterization pitfalls that snared earlier Murphy projects. Bette And Joan takes place in the mythical old Hollywood that only exists in the nether regions between the history books and the gossip columns. Watching the series is akin to looking at a slide show of Golden Age glamour shots while Hedda Hopper and Kenneth Anger unload dump trucks full of dirt over the soundtrack. They’d make a better Greek chorus than De Havilland and Joan Blondell (Kathy Bates), who frame the events from the vantage point of a 1970s documentary about Crawford. Those tiresome flashforwards are more like Wikipedia butting its way into the voiceover booth, a biopic’s predilection for putting too fine a point on information and situations that are more elegantly telegraphed by Sarandon’s and Lange’s performances. It’s a device that enlivened and elevated the most recent edition of American Horror Story, and it contributes to the way in which Feud playfully blurs fact and fiction, but it’s unnecessary. But it wouldn’t be a Ryan Murphy production without at least one element you’ll want to flick off the screen.

Reviews by Gwen Ihnat will run weekly.