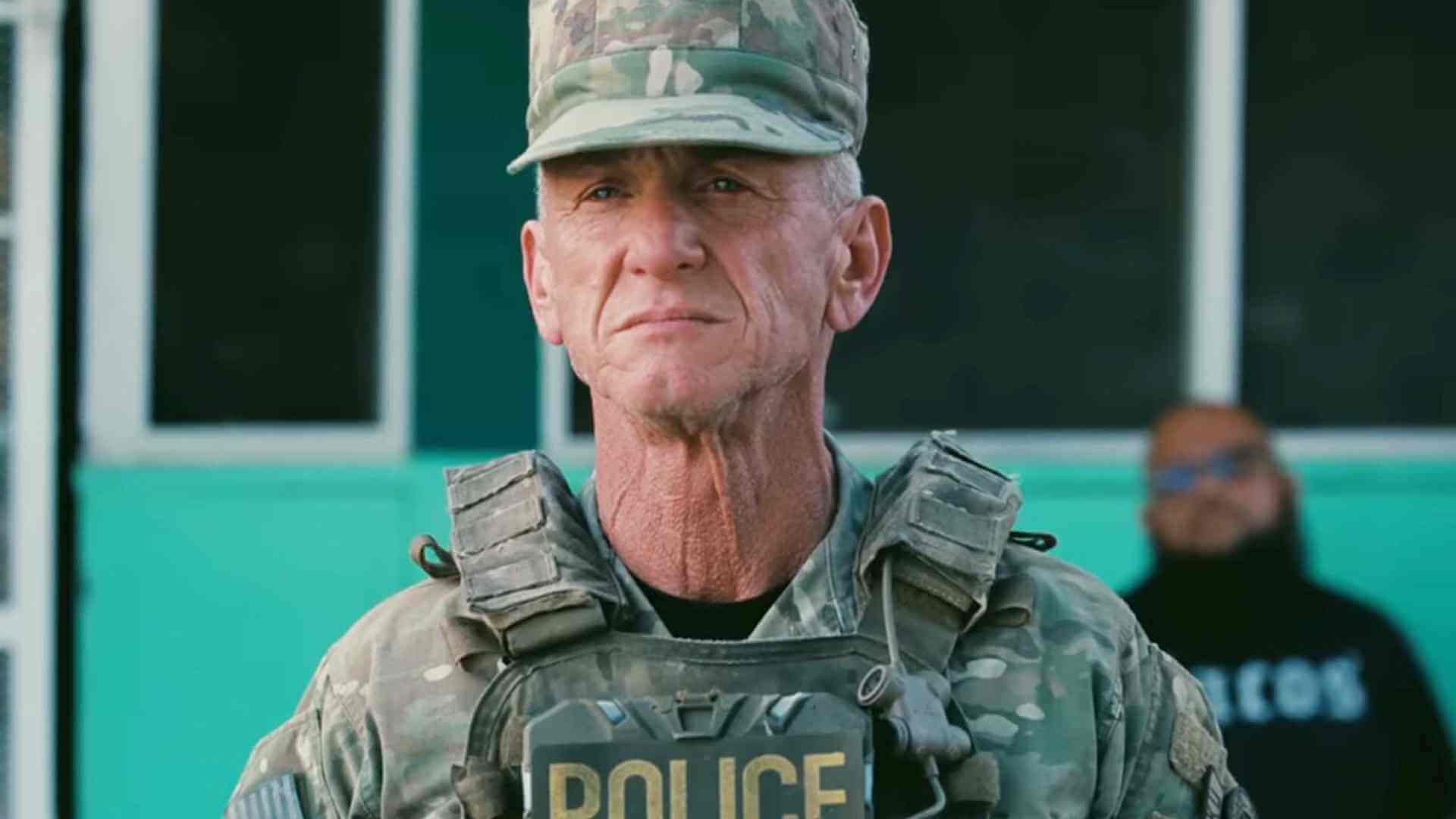

At its core, One Battle After Another is about one racist’s inability to accept his sexual desires and his decision to make that everyone else’s problem. His coercive relationship with Perfidia, which allows him to act on his feelings, ends with an attempt to subjugate her further. This sets the whole plot in motion. He forces her to rat out her comrades and pushes her into witness protection, where she can be safely hidden as his dirty little secret. After Perfidia flees from Lockjaw—a more desperate flight than she’d previously taken from her lover Bob (Leonardo DiCaprio) and their daughter Willa (Chase Infiniti)—the colonel gives his life meaning by applying to the Christmas Adventurers Club, the white nationalist organization apparently at the center of American power. However, if they were to find out that Willa was actually Lockjaw’s child, it would disqualify him from membership. To be accepted, he must hide his transgression by any means necessary. His insecurity becomes a town’s terror.

White supremacy invades every element of One Battle After Another through systems of surveillance, enforcement, and resistance. Part of that reveals itself in Bob, née Ghetto Pat, who successfully goes into paranoid hiding after Perfidia’s betrayal. But white supremacy has long had its eye on Bob, whether he knows it or not. In their only meeting, Lockjaw accosts Bob in the supermarket, where the new father is picking up diapers. “You like Black girls?” Lockjaw asks. “I love ’em.” The surprise interaction reflects the pervasiveness and hypocrisy of Lockjaw’s ideology. He’s resentful and jealous of Bob while also reminding him that he’s being watched—if Lockjaw can’t have Perfidia, he can at least flex his power over Bob. But it’s also a confession. Because of this power imbalance, it’s the only time in the film that Lockjaw can express what he actually wants to someone.

What Lockjaw doesn’t get is that he’s just another mark, a pawn, for the Christmas Adventurers Club. He even walks like a strung-up marionette. They will never accept him, despite his willingness to terrorize non-white communities. Before he can even give Willa a DNA test, the shadowy admissions council plans on tossing him into the incinerator. That he debases himself further for their approval—surviving their assassination attempt in order to spend a few minutes in the crappy corner office of his dreams before the nerve gas begins to flood in—shows how little solidarity exists at the North Pole. It’s all in-fighting, purity tests, and self-loathing. That’s the truth about white supremacy: No one will ever be white enough for the people at the top. Like so many neo-Nazi foot soldiers, white nationalist mouthpieces, and violent ICE agents, Lockjaw is a means to an end for someone in power. Nothing more.

But on the other side of this Battle, resistance springs eternal. For pretty much everyone other than Bob, white supremacy isn’t something they can hide from. They’ve been living around it for so long that resisting its threats has become a casual and instinctive response. When a radio operator is snatched from his post, a pair of neighborhood kids jump on the mic to air an emergency transmission. When Bob needs to escape from Lockjaw’s military forces, invading the sanctuary city of Baktan Cross, his daughter’s martial arts sensei, Sergio St. Carlos (Benicio del Toro), cracks a Modelo and lends him a hand, despite having a “Harriet Tubman thing going on” with the rest of the town’s immigrant community. Supported by an unbothered and enthusiastic network of skaters and nurses, Sergio fends off the military and shepherds Bob out of town without breaking a sweat. Sergio’s network shows the forces organically formed to stop white supremacy, the underfunded community-building required to prevent the state from flattening us into homogeneity. Bob has always aligned himself with the opposition, and that’s why he gets the happy ending—one where he can learn to ease his paranoia and where Willa can join the cause to fight the next battle.

Anderson does all this without making it explicit to the contemporary political landscape. There are no red baseball caps. No messages scrawled on bullets or warnings about online radicalization. This isn’t adapted from a doomscroll. Rather, he structures the fight against white supremacy like it’s Terminator 2: Two men in pursuit of the next generation, a necessary and humanistic battle for the future that we’re all already fighting.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.