Spoiler Space offers thoughts on, and a place to discuss, the plot points we can’t disclose in our official review. Fair warning: This article features plot details of Thunderbolts*.

When Marvel first rolled out the “official” title for Thunderbolts*, asterisk hanging off the back of the name like an unexpected Kurt Vonnegut butthole, it was a clear sign that franchise shenanigans were afoot with Marvel’s latest super-team blockbuster. (The studio attempted to defuse some of the speculation with a trailer last year, which tried to “explain” the added punctuation with a joke about how the team couldn’t settle on a name, but nobody was fooled.) Sure enough, when Jake Schreier’s film ends—one that’s surprisingly grounded, for a movie where Julia Louis-Dreyfus channels her best Selina Meyer while a floating shadow god whisks half of New York off into a series of “interconnected shame rooms”—it’s with a reveal that the title of the movie was a fake: Sorry, suckers. You’ve actually been watching The New Avengers all along.

It’s a pretty good twist, building on themes the film lays solid track on, with its crew of rogue agents and killers trying to do something better with their lives—and maybe get a little bit of the recognition that “clandestine killers working in the shadows” are de facto denied. The film’s creative end credits sequence does an even better job of building on the twist, showing the world react to these new “heroes,” not necessarily with open arms. (Someone deserves a raise for the decision to damn the team with the extraordinarily faint praise of a ringing endorsement from New York Times op-ed columnist David Brooks.) But the reveal that this crew of murderous misfits are now “the Avengers”—or at least “an Avengers,” per the film’s post-credit scene—isn’t just about making sure there’s an actual Avengers team around when Avengers: Doomsday rolls out next year: It’s also an incredibly clever callback to the Thunderbolts’ comic book origins.

So, let’s take a brief flashback to 1996, when Marvel Comics was a comic book company in extremely dire straits. Sure, Spider-Man and the X-Men were selling well, but many of the company’s “biggest” heroes (including pretty much all of the core Avengers) couldn’t move a book to save their fictional lives. The solution: “Heroes Reborn,” a one-year event in which the Fantastic Four, Captain America, Iron Man, and more would essentially be outsourced to former hotshot Marvel artists Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld, who would reboot the characters in an alternate reality to fit their more extreme and muscle-bound tastes. Did it work? Well, Marvel cut its contract with Liefeld after just a handful of issues, citing his inability to keep up with deadlines, and Marvel Entertainment as a whole filed for bankruptcy in December 1996. So, who’s to say? In the more immediate short-term, the sudden absence of these marquee names from Earth-616 left big gaps in the remaining superhero landscape, creating an opportunity for a few writers and artists to plot some clever subversions of the super-team form. Enter the Thunderbolts.

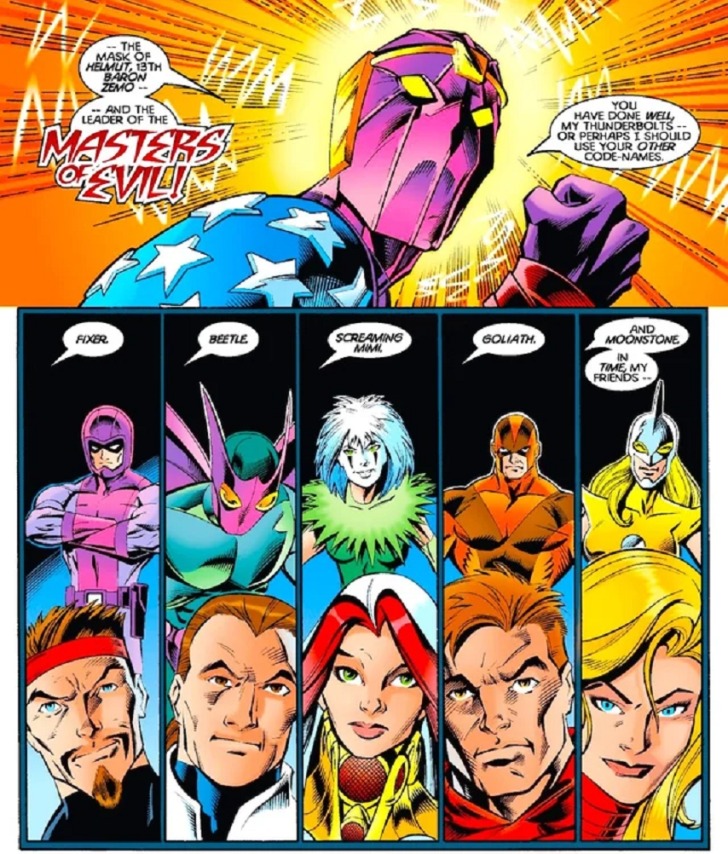

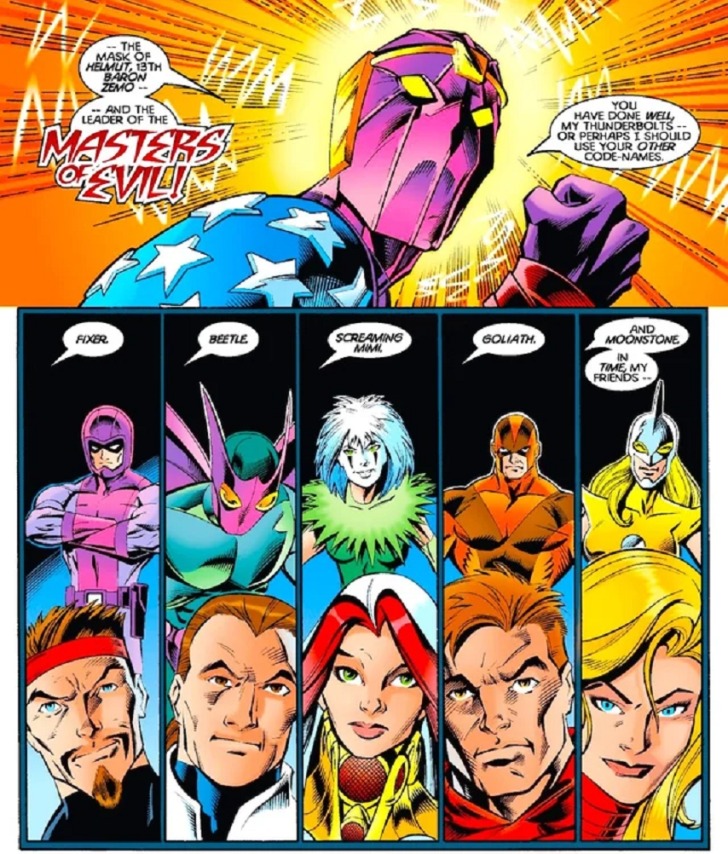

Originally popping up in an issue of The Incredible Hulk in late 1996, the team looked, on the surface, like any number of flashy, disposable new hero groups that comics publishers have tried to generate heat for over the years: They had a fairly generic set of powers (Mach-I could fly, Songbird had sonic powers, Atlas was big and strong, etc.,), some very ’90s costumes, and dialogue that was a mixture of heroic platitudes and bickering in the standard Marvel house style. Comics fans shrugged and accepted the new infusion of B-list fodder, at least until the team’s solo book rolled out the following February. That was when writer Kurt Busiek and artist Mark Bagley finally pulled the trigger on one of comics’ best-hidden twists, revealing—on the book’s final page, after 20 pages of generic superhero adventure—that the Thunderbolts seemed kind of generically familiar because they were familiar Marvel characters: Specifically, they were The Masters Of Evil, classic foes of the Avengers, now in disguise and taking advantage of the absence of the planet’s biggest heroes in order to con the world into letting them take control.

Thunderbolts #1, 1997. Image: Marvel

It was a twist that worked on multiple levels, including the then-novel shock of Marvel masterminding a genuine surprise. The company had gone out of its way to keep the team’s secret secret (including hiding details from solicits for future issues), and most fans genuinely didn’t see it coming. At the same time, the core tension of the premise gave the book an actual hook, far better than any simplistic “We’re a team and we fight bad guys!” title could have done. By centering on a group of often-deadly outcasts doing good for bad reasons—and then discovering that helping people can actually feel pretty nice—Busiek and Bagley turned a bunch of characters who had mostly existed to sneer and then get smacked in the face with a flying shield into real people, with real feelings. (One standout early issue has Mach-V—actually long-running minor Spider-Man villain Beetle—forced to team up with the wall-crawler, only to be forced to come to terms with the fact that Spidey really is as good a guy as everybody says.) Although team leader Baron Zemo was unrepentantly resistant to any such softening, the first run of Thunderbolts saw many of its villainous characters make the leap from faux-heroes to the real deal. (At least, until “Heroes Reborn” wrapped up, bringing the real Avengers back into the fold, and Zemo spitefully revealed his team’s true identities to the world.)

Thunderbolts* plays with the comic’s legacy in ways that are, at least in hindsight, obvious: With the exception of David Harbour’s jokey Red Guardian, each of the team’s core members has been the “villain” of a previous Marvel installment, from Yelena Belova trying to revenge kill Clint Barton in Hawkeye, to Bucky Barnes’ stint in Captain America: The Winter Soldier. And all of them, at the film’s climax, agree to essentially participate in a con not all that different from Zemo’s: Stealing the abandoned Avengers name, in a world deprived of heroes, to try to do the best with it that they can. (The film also plays with ideas from later Thunderbolts comics, notably the Dark Reign period from circa 2009. Those books saw ‘bolts team leader Norman Osborn basically take over the United States, substituting his crew of killers and degenerates, in shiny new costumes, as the “official” Avengers.)

In the run up to Thunderbolts*‘ release, it was distractingly easy to dismiss the film as a blatant knockoff of DC’s “bad guys do dirty work” Suicide Squad movies. (The “We Demand To Be Taken Seriously“-themed trailers trying to paint the movie as elevated indie art certainly didn’t help.) But Florence Pugh and her cohorts not only put together a much better and more thoughtful character study than the movie’s logline might suggest, they’ve also made a real, unexpected effort to tackle the core ideas of the Thunderbolts comics. (Without even getting into the deftness with how the film uses Lewis Pullman’s “Bob,” a character with his own twist-y, sometimes extraordinarily messy, history with Marvel.) Because Thunderbolts, as originally conceived, was never just about bad guys getting forced onto a team. Instead, it played with ideas like the superhero team as a deliberate branding effort, the interplay between altruism and selfish motivations, and the basic question of why people do good, all wrapped up in a package where heroic identities are never as clean and simple as their logos might suggest. Schreier’s film tackles these ideas head-on, while its final twist—hidden behind that deliberately obnoxious asterisk—reveals how clearly he and writers Eric Pearson and Joanna Calo grasped the assignment set out for them by 30 years of meta, subversive stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.