Steven Spielberg is no stranger to the double feature. At least six times in his career—seven if you’re a Poltergeist conspiracist—he’s released two films in one year. These moments often distilled the central push and pull of his career: The ease with which he delights through action and horror, and his desire to be taken seriously with historical drama. His 1993 pairing of Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List represented his two sides: spectacle and real-life drama, an expert craftsman wrangling monstrous productions who could make intangible atrocities palatable for general audiences. This ability would become even thornier in the post-9/11 landscape, when his black-and-white world would take on shades of gray. Released six months apart to the day in 2005, War Of The Worlds and Munich would make for cinematic bookends that wouldn’t merely prey on people’s fears about the War on Terror, but would integrate them into something larger. One imagined a 9/11-style attack as a sustained, world-shattering campaign; the other asked audiences to empathize with their attackers. Both dealt not just with actions, but with consequences. As the Mossad accountant in Munich puts it: “No matter what you’re doing, someone’s paying for it.”

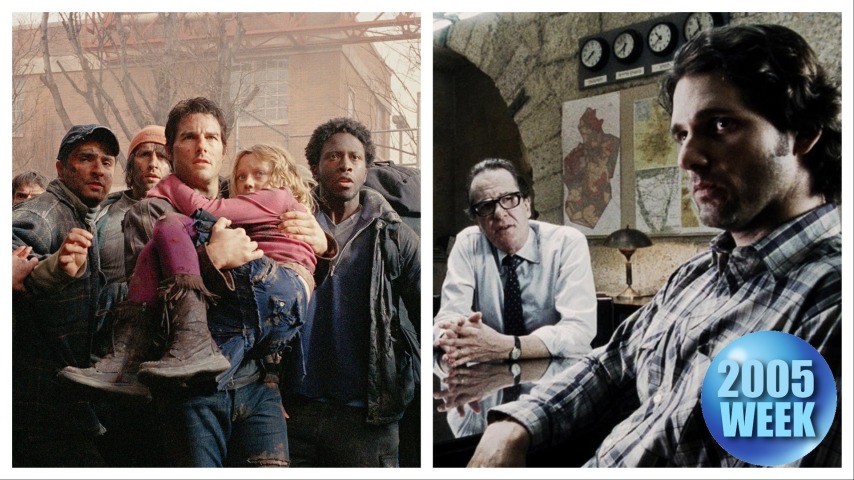

Although War Of The Worlds came out in 2005, it feels distinctly lodged in 2001. The Clinton ’90s had lulled Americans, particularly the white middle class, into believing that the good times would keep rolling, as neoliberalism had supposedly taken humanity as close to utopia as it was likely to get. “With infinite complacency,” Morgan Freeman narrates in War Of The Worlds‘ opening scene, “men went to and fro about the globe, confident of our empire over this world.” That’s the world of War‘s protagonist, deadbeat divorcé and classic Spielberg bad dad Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise), who is still living at the end of history even though his life is already beginning to unravel. His son, Robbie (Justin Chatwin), resents him for never being around; his daughter Rachel (Dakota Fanning) is slowly getting there. Ray has allowed his patriarchal power to decay, and when the tripods emerge, whatever control he assumed he had over his life goes up in smoke.

Opening in Bayonne, New Jersey, just a half-hour drive from the Twin Towers, the 9/11 imagery of War Of The Worlds was immediate. Spielberg was adapting the grainy video footage of post-attack news reports as much as H.G. Wells’ seminal invasion story, with plumes of smoke, ash, and dust enveloping Bayonne as tripods vaporized New Jerseyans. The film’s street-level perspective shows Ray chasing Spielberg’s camera as he escapes the collapsing buildings and aliens rising out of the ground. Crumbling buildings are a prerequisite for the last act of every blockbuster these days, but few, if any, movies capture the sudden realization that the world has irrevocably changed. Then it continues. War Of The Worlds starts at 9/11 but imagines the attacks were unending and the result of an insurgency that could spring at any time. There’s no prevention, because the enemies are already here. The Ferriers are at the whim of the overpowered, technologically advanced killing machines that descend whenever they find anything resembling aid or shelter. The title of the film is a misnomer. It’s not a war, it’s a slaughter.

War Of The Worlds isn’t Independence Day. There is no presidential speechifying or global unity. It is a reactive movie, one about escape and survival, one where its characters and government have no control over the outcome. The film’s ending is even more passive, concluding in favor of Ray and Earth as if part of a grand, intelligent design. “They were undone, destroyed, after all of man’s weapons and devices had failed, by the tiniest creatures that God and his wisdom put upon this earth,” Freeman says. Spielberg’s ending backs the film into a truly American corner, one of individualism and faith, where a family survives unscathed because of Ray’s commitment to their safety.

Half a year later, Munich would come to an inverted conclusion. Removed from the safety of sci-fi genre trappings, Spielberg portrays a man of faith, both in God and country, who separates from his family on a mission in service of both. That mission would be his undoing.

Munich recounts the aftermath of the massacre at the 1972 Olympic Games, during which 11 Israeli athletes were held hostage and killed by the Palestinian militant group Black September. As a show of force, Israel launched a secret initiative to assassinate 11 of the architects of the massacre. “I’m always in favor of Israel responding strongly when it’s threatened,” Spielberg told Time in 2005. “At the same time, a response to a response doesn’t really solve anything. It just creates a perpetual-motion machine.” Spielberg found himself in unfamiliar territory with Munich, a movie that outright asks if Israel’s participation in this perpetual-motion machine is killing the Jewish soul.

“Every civilization finds it necessary to negotiate compromises with its own values,” Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir (Lynn Cohen) says early in Munich. Spielberg and his screenwriters, Tony Kushner and Eric Roth, were intent on portraying the psychological toll of Meir’s negotiations. The compromise that would arise from them costs Avner (Eric Bana), the Mossad agent tasked with leading a team of assassins, his humanity, as he leaves his wife and newborn to head out on a psychologically devastating, years-long revenge mission ordered by the Israeli government. The more time Avner spends on the mission, the more he sees his targets as people. He kills one of his targets, writer Wael Zwaitter (Makram Khoury), in his apartment after a public reading of his new translation of The Arabian Nights. Another, Mahmoud Hamshari (Igal Naor), is blown up moments after his daughter leaves the house. It’s sheer luck that the attack doesn’t kill her too.

The complexity with which the script portrays these targets, and Avner’s growing empathy for them, makes for a somber espionage thriller. In the film’s most incisive scene, Avner’s team ends up sharing a safe house with their would-be victims. After finding some common ground in Al Green, Avner becomes embroiled in a debate over the Palestinian state with Ali Hassan Salameh (Mehdi Nebbou), the chief of operations for Black September who is unaware that Avner is a Mossad agent. “You don’t know what it is not to have a home,” Ali tells Avner. “We all pretend we care about your international revolution…but we don’t care. We want to be nations. Home is everything.” This idea resonates throughout Munich, as Avner finds himself increasingly stateless. He cannot join his family in America, where they’ve moved for safety, and he cannot return to Israel because they’ve “never heard of him.”

Avner’s Mossad contact, Ephraim (Geoffrey Rush), depends on his soldiers to be like one of the alien tripods—a being who can coldly and indiscriminately kill without remorse. Four years after Operation Enduring Freedom began, during which they regularly heard about increasing insurgency, many Americans were also contending with the idea that their vengeance quest wasn’t worth the cost. Avner echoes this disillusion. In the film’s final scenes, he becomes convinced Mossad has added him to their hit list and is surveilling his family. He becomes paranoid that both Israel and Black September are after him. By the end, he’s gone full Conversation, gutting his mattress and disassembling his landline in search of a bug.

In his final meeting with Ephraim, standing in the shadow of Manhattan, Avner interrogates him. He asks if Ephraim made him into a murderer, acknowledging that they should have arrested the perpetrators like they did the Nazis and demanding evidence that “every man we killed had a hand in Munich.” Ephraim refuses. “We are telling them: If you kill us, you will never be safe,” he says.

Closing on a shot of the World Trade Center, Munich brings the conversation to the present day, directly reminding American audiences of the cost of these escalations. Unlike in War Of The Worlds, the common cold won’t solve the dilemma. Twenty years later, Israel’s attacks on Palestinians have now adopted the cold indifference of War Of The Worlds, where IDF soldiers celebrate the killing of civilians seeking aid. The attacks seem endless, a new Ray Ferrier is created every day, and the “perpetual-motion machine” continues unabated. Late in Munich, Avner’s bombmaker quits the mission. “We are supposed to be righteous,” Robert (Mathieu Kassovitz) says. “That’s a beautiful thing, and we’re losing it. If I lose that, that’s everything. That’s my soul.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.