The real answer, then, is that The Pyramid wants the realism and immediacy (and, if applicable, money) of the found-footage effect, but won’t commit to the visual stigmas that often accompany that format. Yet immediacy doesn’t require films within films. Director Grégory Levasseur, as a longtime screenwriter-producer for Alexandre Aja (who dutifully produces here) and a professional filmmaker, should not be unaware that point-of-view or handheld shots are permissible without the on-screen excuse of camera-toting characters. But that’s how his movie comes across: confused about how much explanation filmed images require. It’s just a few degrees away from a movie that sends a fully equipped big-budget film production into the pyramid to explain why most of the time, the images will be clear, but occasionally, the camera will be jostled.

Here, the jostled cameras belong to Fitzie (James Buckley) and Sunni (Christa Nicola), the “documentarians” who sound more like they’re prepping a segment on the Today show, as well as adventurous young archeologist Nora (Ashley Hinshaw) and her more cautious father Holden (Denis O’Hare). All of the characters speak in fluff-journalism exposition with a touch of questionable phrasing. (At one point, one character challenges another to stop acting like an archeologist and “start being a human being.”) They’re a tedious bunch until they enter the uncovered pyramid to investigate what happened to their expensive, Wall-E-like robo-camera—at which point they become a tedious bunch of dimly lit creature fodder.

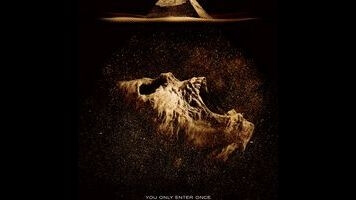

Once The Pyramid’s mayhem begins in earnest, Levasseur seems less concerned about how he might justify as many shots as possible, and captures some arresting images with whatever cameras he has on hand. The first on-screen death is startling and memorably gruesome, and Levasseur uses the dull lighting to his advantage for an impressionistic sequence where the crew races through a hallway rapidly filling with sand, which pours from the walls in endless streams.

But these B-movie touches aren’t especially scary, and the characters are too paralyzed with fear to have much fun with the silliness. The movie further undermines its own sense of fun by conjuring a cool primary antagonist, then hiding it in plain sight by using the sometimes-found footage to fudge some special effects. In the end, The Pyramid seems designed not for horror, adventure, or action but to provide every possible answer to the question of its found-footage bona fides—yes, no, or maybe, depending on who’s asking. It spends most of its running time hedging uncertainly between trend and backlash, explanations and excuses.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.