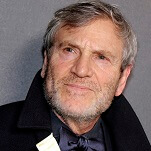

During the director’s commentary for Monty Python And The Holy Grail, co-director Terry Gilliam offers a fascinating insight into the creative differences between himself and the film’s other director, Terry Jones.

“When we were cutting the film, Terry would look at a shot and remember what the day was like, and the atmosphere around us, and also the things that were happening that the camera didn’t see,” Gilliam says, “and would kind of imbue the shot with more importance, or more atmosphere, or more character, or more something than it was.”

For Gilliam, it was at least a slight source of frustration, as he—Monty Python’s resident visual artist—was always more interested in the information conveyed by each frame. Gilliam was thinking purely in terms of how to assemble a cut of a film through what the camera told him, while Jones was recalling the entire emotional context behind every shot, every scene, every day of making Holy Grail, the feature directorial debut for both Terrys. It’s a striking observation, one that underlines not just how Gilliam would work as he moved on to solo directing jobs packed with unbridled and handmade visual awe, but how Jones functioned as a filmmaker and cornerstone of Python’s success.

One of the most quoted, most influential, and most uproarious comedies ever made, Monty Python And The Holy Grail turns 50 this year, and the occasion will no doubt launch new tributes to the film. These tributes will be filled with memorable lines, musings about killer rabbits and French knights, and odes to the collective comedic might of Python as a troupe. But a figure that always deserves more attention is Terry Jones, the quiet genius of the group, who imbued Holy Grail, and Monty Python’s entire body of work, with an erudition, sensitivity, and creative audacity which made him an indispensable, if lesser-known, star among stars.

When the public at large thinks about Python, they tend to think about the biggest names. John Cleese went on to huge success as a film and TV star. Terry Gilliam became one of the most celebrated filmmakers of his generation through classics like Brazil and 12 Monkeys. Eric Idle eventually brought Python to Broadway, while Michael Palin forged a whole new career as a now-legendary travel writer and TV presenter. Graham Chapman never got his second act, dying of cancer in 1989 at the age of just 48, but he established himself during Python’s run as the best pure actor of the group.

Then there’s Terry Jones, who was the sole directorial force behind Python’s other two feature films, Life Of Brian and The Meaning Of Life, then moved forward into directing features like Erik The Viking and The Wind In The Willows, and delving into medieval history with books and TV series like Medieval Lives. As a visual stylist, he continued to mature, but what sets Erik and Wind apart from the rest of the troupe’s creations is Jones’ curiosity about people who see the world differently. Despite their epic proportions, these films are more character pieces than pure visual feasts, while Medieval Lives is one of the essential docuseries of its era, in which Jones compiles everything he’s learned about the Middle Ages with an eye towards educating audiences about the era’s surprising sophistication. His post-Python existence was quiet compared to his surviving colleagues, and as a result he’s faded from the public imagination in ways that Cleese, Idle, Chapman, Palin, and Gilliam never quite have. But looking closer at how Python worked, and why Python worked, much of it is thanks to Jones, who brought the emotional context behind every joke to the fore while adding much of the silliness for which the troupe is beloved.

On that same Holy Grail commentary, Terry Jones attempts to explain how the Python comedy style came about, and outlines his contribution as the “stream-of-consciousness” flow of the original Monty Python’s Flying Circus TV series. Influenced by the work of Irish comedian Spike Milligan, as well as some of Gilliam’s pre-existing, more free-flowing animation, Jones envisioned a comedy show that would abandon the conventional structures of sketches and scenes with setups and punchlines, and simply move on as the spirit of the piece required.

“If we get half a sketch that works and the rest of it doesn’t, well we’ll just have a half a sketch and flow into something else,” Jones explains.

This resulted in Monty Python’s legendary transitional devices, like Gilliam’s animation, Chapman appearing in military garb to declare a sketch “too silly” to continue, and Jones sitting nude at a pipe organ to play one sketch off and play the next one on. It’s a laissez-faire style exemplified by a sketch in which two old ladies (Cleese and Chapman) argue over the presence of a penguin atop their television. Fittingly, it’s Jones who ends the sketch by appearing on said television and declaring that it’s time for the penguin to explode, which it promptly does.

This anarchic, free-flowing spirit carried forward into the Python films, most notably Meaning Of Life, which is itself a thematically linked anthology of sketches. Life Of Brian is the Python film with the greatest focus on narrative, but in Holy Grail, the quest at the center of the film feels almost incidental to the jokes, and you can feel Jones’ influence as it careens wildly from subplot to subplot, often dropping plotlines smack in the middle of scenes (like Jones’ young Prince Herbert never quite getting to burst into song) and leaving others dangling hilariously (as when Gilliam’s animator suffers a fatal heart attack, thus ridding Arthur and his knights of a cartoon monster). Jones’ stream-of-consciousness comedy philosophy gave the entire Python troupe, and by extension Holy Grail, that wonderful ability to throw the audience off-balance.

It was also Jones’ idea to set the film entirely in a medieval aesthetic (save for the ending, of course), abandoning the original screenplay concept which saw the film unfolding half in the Middle Ages and half in the present day. Jones was fascinated by medieval Britain at the time, and notes on the commentary track that, while the film is set in the 10th century, the costume and sets evoke the 14th because it was more evocative of a classic medieval feel. Characters comment on the strange nature of medieval life, whether arguing over witchcraft or picking apart the logic of the Knights Who Say “Ni,” and while the screenplay is credited to the entire Python troupe, it’s hard to imagine anyone but Jones steering the ship in these history-geek moments, fascinated and tickled by the world Python’s built. For all its focus on visual gags and outright lunacy, Holy Grail is also a great character comedy, whether Bedevere is attempting to impose malformed science onto the whole mess, or a guilty Lancelot is festering over having massacred an entire wedding party. These moments work because Python’s members are great performers, but also because Jones was there on the day and in the editing room, maintaining the character beats and emotional consistency, finding the subtle textures in his castmates’ turns.

Gilliam went on to be the better filmmaker. His animator’s eye for drama and atmosphere, paired with the smoke-strewn compositions of cinematographer Terry Bedford, gives Holy Grail a real sense of period-appropriate gravity. Gilliam’s post-Python work continued to showcase an evolving artist, while Jones’ gifts peaked with Meaning Of Life. But Jones was the greater master of narrative and character comedy. Gilliam credits Jones with being better at working with their castmates to get the right tone for any given scene, going about it gently, subtly, while Gilliam—who was used to pencil and paper doing whatever he willed—was too forceful for his friends.

This emotional intelligence extends to Terry Jones the performer. As Sir Bedevere the Wise, he creates a double act with Chapman’s King Arthur. They’re both often the straight man in any given scene, but Jones has the task of playing things perfectly straight while believing that a witch weighs the same as a duck. He’s also got Bedevere’s flip-up visor, which is a remarkable piece of physical comedy, particularly when he’s lifting it up in moments of peak drama and peril.

Throughout the film, Jones delivers some of the best pure character moments. He steals scenes as the meek Prince Herbert and the screeching wife of Michael Palin’s politically-minded peasant Dennis, but it’s Bedevere that’s the true achievement, because he has to spend so much time reacting, analyzing, observing the more ostentatious knights. Even behind that helmet, mustache, and annoying visor, his expressive eyes tell the story of a guy who’s loyal to Arthur to a fault and who’ll commit to even the wildest theories if they’re backed by his scientific mind. Bedevere doesn’t get a side quest of his own, which means Jones is always sharing the screen, always giving to his co-stars with funny looks and sounds. In other words, he’s the guy always trying to read the emotional room, and you can see it in his eyes when you watch Holy Grail closely. His turn is a welcome piece of comedic restraint in a completely zany movie.

The great joy of watching Monty Python is the sense that, when the lights come up and the show starts, its members are thinking and performing with one brain. In reality, the troupe was an often conflicting mesh of comedic and personal philosophies, with all the arguments and tension that entailed. In a group like that, the loudest and most audience-facing voices stand out, which explains why Cleese and Idle remain comedy idols even to casual fans. But without the emotional intelligence and wit of Jones—whose wisdom and passion for upsetting the balance of typical comedy guided Holy Grail to greater heights of absurdity—the movie that changed comedy filmmaking 50 years ago wouldn’t exist. The film’s ability to shapeshift throughout its runtime, to act not just as a single story but as one unbroken parody of epic British cinema, comes from him.

In the final minutes of Monty Python And The Holy Grail, Bedevere and Arthur make their final approach to what they believe to be the Holy Grail. The movie ends with police swooping in, confiscating the cameras, and arresting the knights, but just before that, Arthur summons an army out of nowhere while Bedevere looks on, astonished and emboldened. Gilliam’s directorial gifts provide the visual atmosphere, but it’s Jones’ focus on the actors, on the heart of the moment, that makes the audience, just for a second, believe that this is all really going to work. It doesn’t, of course, and in true Terry Jones fashion the film drops the narrative rather than completes it, but for just a moment it feels like an epic end to a long quest. Gilliam could have made it look epic, but Jones made it feel that way.