Stephen King will never be done with Holly Gibney

The character, who's appeared in 11 King stories, represents one of the most unusual developments in his work.

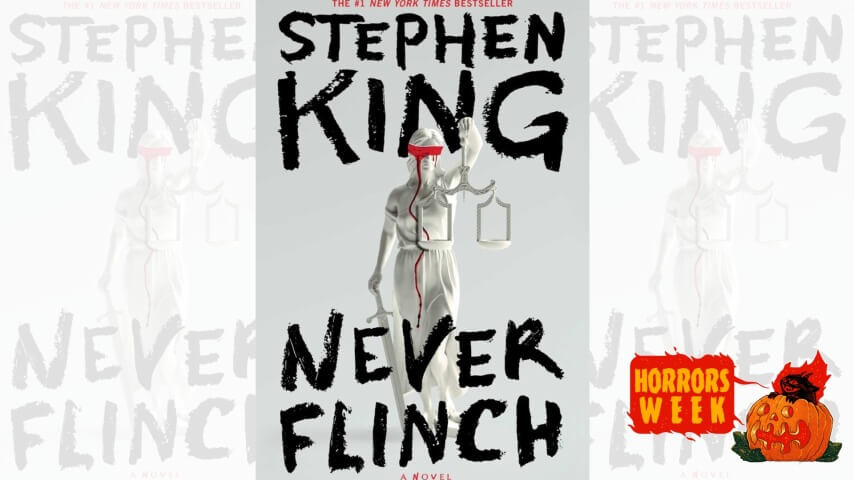

Last May, Stephen King released Never Flinch, a crime thriller featuring private investigator Holly Gibney. Holly first appeared as a secondary character in Mr. Mercedes; since her introduction, she’s become a clear favorite of the novelist’s, appearing in 11 different novels and novellas. Much of the last decade or so of King’s career has been unusual, as the writer has focused more and more on crime thrillers over his usual supernatural fare (while not forgetting the latter entirely), but Holly is the strangest development of all. In a bibliography that largely eschews both sequels and recurring protagonists, Ms. Gibney is an exception to the rule whose existence suggests something more than just a fondness for clever ladies with bad nerves.

To understand Holly’s importance, it’s useful to go all the way back to the beginning with Carrie, King’s long-form debut. By now, the story of an abused teen who gets violent revenge on her peers one fateful prom night is a familiar one, thanks to multiple film and television adaptations. But the original novel remains strong, if a little stiff, thanks in no small part to the empathy readers’ feel for Carrie’s plight. She is, in her small way, emblematic of millions of small town girls whose shyness and struggles with socialization made her an easy target for teens eager to prove themselves part of the herd.

What’s odd, then, is King’s revelation in On Writing that, while he pitied Carrie White, he believes he never truly understood her. On revisiting the novel, it’s possible to see what he means; while Carrie is portrayed sympathetically, there’s a distance between her and the third-person omniscient narrator, a kind of kid glove approach that’s not present with the other characters. Take Carrie’s mother, Margaret: a towering, abusive monster, a religious zealot whose excesses would border on camp were she not such a direct physical threat. When King writes through her eyes, the gloves are gone—there’s no sympathy for Margaret’s excess, but the writer clearly enjoys the over-the-top intensity of her vision.

Going forward, this distinction would become more clear. King’s “normal” women protagonists (think Sue Snell in Carrie; Susan Norton in ‘Salem’s Lot; Wendy Torrance in The Shining, etc) all tend to be normal in a very narrow, specific way—Sue’s big concern in Carrie is whether or not her boyfriend got her pregnant, and while Wendy Torrance has the distinction of being abused, there’s not a whole lot about her beyond that.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)