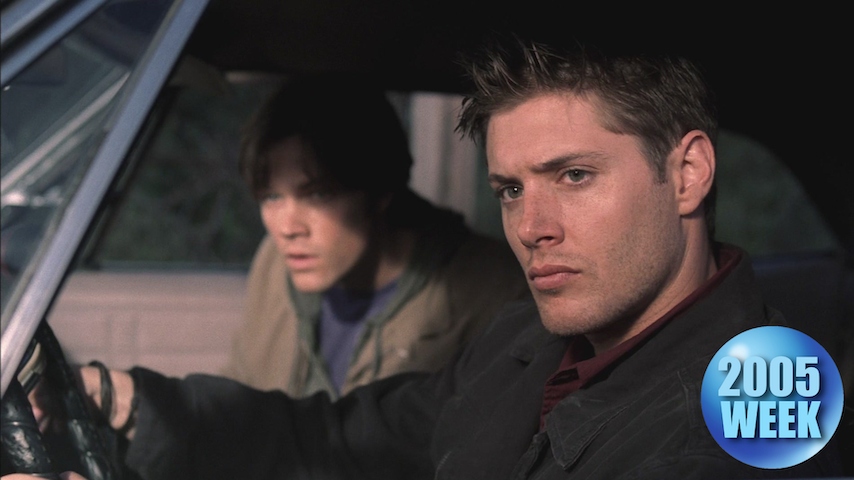

For teens in 2005, Supernatural proved to be a gateway to modern horror

Before it lost itself to fan service, Eric Kripke's show was a genuinely scary, proto-version of the grief-based thrills that rule the genre today.

Screenshot: Netflix/The WB

A boy walks into a dark room and sees the charred remains of his father lying on the floor. As he stares, the camera pans to reveal a vision so ghastly that it makes that initial horror feel almost comforting, like something from a Sunday morning cartoon or perhaps a Goosebumps novel. The ashes aren’t moving. The mom hovering over her son on the ceiling sure will though.

Anyone still jumpy around telephone poles seven years on will recognize that as the start of one of the scariest scenes in Hereditary, a film The A.V. Club deemed “the most traumatically terrifying horror movie in ages.” I’m not going to pretend my stomach didn’t leap so high into my throat it felt like it would join Toni Collette’s character on the ceiling the first time I watched it. But something about the scene also felt oddly nostalgic, as if I’d seen it somewhere before.

I had the same feeling the first time I watched The Haunting Of Hill House, a series The A.V. Club called, quite similarly to the film rave above, “the most traumatic horror story of the year.” That time, it was in response to a scene in the premiere, in which a flawed but ultimately well-intentioned father scoops up his son and tells him to close his eyes and not look back under any circumstances as he sprints toward the door of his very haunted house. As they reach the car, the boy’s terrified siblings, who had already been ferried to safety, beg and plead for their mom, who they’ll never see alive again. In a moment of pure terror, the dad had decided to save his kids and leave their mom behind in that cursed home with all of its ghosts and darkness. It’s the foundational wound that would go on to determine—and, for some, ultimately destroy—the rest of his kids’ lives.

This time, I knew exactly why the scene felt so familiar. I’d seen one just like it before in another pilot that had aired more than a decade prior. The image of John Winchester (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) ordering his young son to take his brother outside and not look back (“Now, Dean. Go!”) bubbled up like it was the defining episode of my own childhood. In a way, it was—at least as it would go on to dictate a thirst for anything that can reasonably be labeled “traumatically terrifying” that I’ve never quite been able to quench.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.