American cinephiles who are curious about the legal process in other countries are having a banner year. A few months ago, Gett: The Trial Of Viviane Amsalem received rave reviews for its harrowing depiction of an Israeli divorce court; among its many virtues, the film is notable for never leaving the courtroom and its adjacent offices, with the outside world glimpsed just once, fleetingly, from a window. Now along comes Court, an absurdist drama about a trial in India that takes almost precisely the opposite structural approach, devoting as much screen time to the mundane personal lives of the prosecutor, the defense attorney, and the judge as it does to the case itself. That both films are excellent demonstrates how many different, equally rewarding ways there are to tackle any given subject. That both films are upsetting to watch suggests that few countries have ever devised a legal system that doesn’t regularly screw people over.

Initially, there’s at least some ambiguity regarding the case of Narayan Kamble (non-professional actor and real-life activist Vira Sathidar), a folk singer who’s arrested and charged with having abetted the suicide of a sewer-maintenance worker. Kamble had performed near the dead man’s home just two days before the corpse was discovered underground, and prosecutor Nutan (Geetanjali Kulkarni) presents a witness who states that one of Kamble’s songs at that concert urged impoverished workers to shed light upon injustice by killing themselves. Kamble’s own prickly testimony, in which at one point he claims not to have written such an inflammatory song “yet,” doesn’t exactly endear him to the judge (Pradeep Joshi), nor to the viewer. As the trial continues, however—like the one in Gett, it keeps getting postponed and restarted for various dumb reasons—Kamble’s defense attorney, Vinay Vora (Vivek Gomber), proves almost conclusively that the death in question was an accident, not suicide, unmasking the state’s star witness as a liar-for-hire and the investigating officer as an incompetent bumbler. When it looks like an acquittal is in the cards, however, the authorities simply find a new reason to arrest Kamble and start the process again.

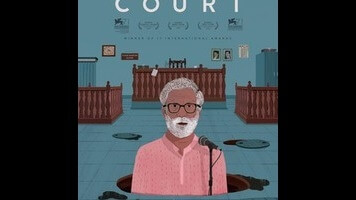

Remarkably, Court is the first feature written and directed by Chaitanya Tamhane, who at 28 possesses the formal assurance of a filmmaker with plenty of experience. Tamhane shoots the courtroom scenes using stark, fixed angles, but the heart of the movie consists of the more fluid sequences that follow the characters around as they go about their daily business. One gorgeous, subtly revelatory shot pivots around Vora in an upscale bar to showcase a woman singing pop songs in English and Brazilian; there’s no dialogue at all (apart from the singer’s stage banter), and the scene doesn’t advance the story, but it’s one of many ways that Court emphasizes the defense attorney’s wealthy, privileged background, which makes for a stark contrast with the profession he’s chosen. (When Kamble is finally granted bail, after months in detention, Vora pays it, knowing it’s unlikely that he’ll ever see the money again.) At the same time, though, Tamhane refuses to demonize Nutan, the prosecutor, who lives a lower-middle-class existence and treats her job with the bland, obligatory professionalism one would expect from someone in retail. Even the extent to which racism may influence Kamble’s prosecution—he’s Marathi, and there are occasional snide remarks about “immigrants”—gets stealthily underplayed, at least to Western eyes.

Given how strenuously Court avoids creating easy, pat parallels between the personal and the political, it’s a bit disappointing when the film’s epilogue makes precisely that mistake. The final shot, in particular, is way too on the nose. (Nutan’s family also goes to see a play that seems like the theatrical equivalent of Paul Blart: Mall Cop, but with a noxious anti-immigrant bent.) Such lapses stand out because they’re so rare, though. For the most part, Tamhane improbably succeeds in creating a damning courtroom drama that derives much of its power from observing the cogs in the machinery when the machine is switched off.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.