On Virgin, Lorde has never been less certain or more alive

Messiness has never been more meaningful than on Lorde's visceral fourth album.

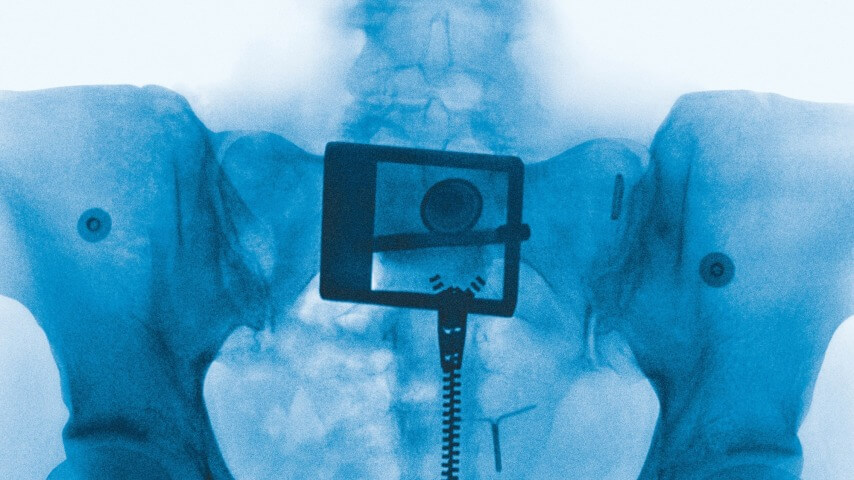

Image: Republic

When Lorde emerged on the music scene at 16 years old, seemingly fully formed like Athena springing from Zeus’s head, preternatural precociousness was part of her appeal. As an old soul immersed in youth culture, the clear-eyed certainty with which she observed her world permeates her early albums. Her knack for putting the exact right words to growing up in the 21st century earned her a cult following of young people who looked to her to make sense of their lives. Even when she rejected this devotion on her last album Solar Power (“If you’re looking for a savior, that’s not me”) she was still a “prettier Jesus” preaching from a place of self-assuredness, the “Girl (Who’s Seen It All)” and could pass on that wisdom to her followers.

Not anymore. On her messy, visceral fourth album, Virgin, Lorde finally manages to take herself off the pedestal. Her immense songwriting talent is still on display, but the lyrics purposely shed the perfect precision of previous work. (Lorde told Rolling Stone that “in the past, I’m really trying to craft these lyrics. This time I was like, ‘No, be smart enough to let it be really basic. Be plain with language and see what happens.'”) The result is urgent, immediate, and alive in a way Lorde has never been before—and few of her peers could accomplish.

There will be inevitable comparisons to Charli XCX’s Brat, which Lorde (who featured on the beloved “Girl, so confusing” remix) has said influenced her own work. Like Brat, Virgin favors straightforward language and makes dance-pop out of heavy introspection, trading in topics like generational trauma and disordered eating. But Virgin is really a return to the form Lorde herself pioneered on her debut album Pure Heroine; the dark, spare electronic beats of that record had a huge influence on subsequent pop music. Virgin marries that Pure Heroine sensibility with the more naturalistic, acoustic sounds present on Melodrama and Solar Power to surprising effect. A single song will veer into drastically different sonic directions that nevertheless feel inevitable by the time it’s over. The lyrical delivery can be syncopated and strange, her typical hyperverbal writing style resistant to easy rhyme or simple resolution. And there are a handful of moments that showcase exciting new sides of her vocal abilities.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.