In the third book, Tobias attempted a red-tailed-hawk form of suicide, flying at speeding-bullet hawk-dive speed, first into a brick wall, then towards a glass skylight. Only the intervention of a few friends kept him from killing himself, ruining the body into which he found himself trapped. The books are for children, so the text doesn’t read, “Tobias was trapped in the wrong body and wanted to kill himself.” And at other points in the series, he seemed to relish the opportunity to fly away from his human troubles, his school bullies and abusive guardians. And still later, through a somewhat ham-handed plot device, he regains the ability to morph from hawk into another creature, including his own human body, for two-hour intervals. His relationship to his sense of bodily wrongness is complicated. Regardless, Tobias’s narration is full of longing and angst, waves of self-disgust each time he chokes down a rodent, grim musings on how long he’ll survive in a wild body that doesn’t match his mind.

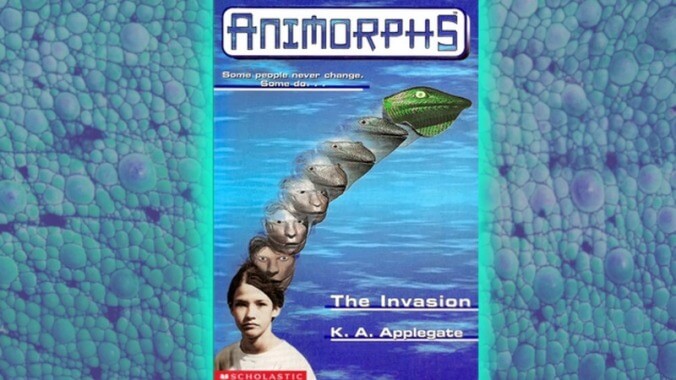

As Adair points out, the canon of books specifically for trans kids has broadened a bit, in that it exists at all. Part of being trans is finding yourself in texts not targeted to or about you, but which gesture toward feelings of dysphoria and dislocation, as well as the euphoria of feeling wholly yourself. Works like Jonathan Glazer’s Under The Skin can resonate more than The Danish Girl or Dallas Buyer’s Club, which can come across as awkward attempts to educate cis folks on the Other. The culture of hate toward LGBTQ people in the U.S. has brutal, unconscionable repercussions on young trans folks, especially. “In Animorphs, no one can find out who you really are. The consequences are deadly,” Adair says. The parallels should be obvious.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.