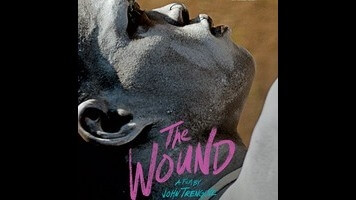

What sort of wound is at the heart of The Wound, South African filmmaker John Trengove’s debut feature? Is it fundamentally metaphorical—an emotional wound, or perhaps a psychic wound? Probably, for those who want to dig a bit, but it’s not as if there isn’t plenty of mangled flesh right on the surface as well. (Readers with delicate sensibilities may want to pre-emptively cringe at this point.) Set among the Xhosa people, who inhabit the southernmost part of South Africa, the film observes a real-life rite of passage in which young men travel to a remote mountain location for what amounts to an extended group camping trip. Which sounds swell, except that the first thing they experience upon arrival is ritual circumcision, performed without anesthetic, or even much in the way of prelude. A man kneels in front of each teenager with a sharp instrument and casually removes the foreskin, lickety-split, as if he were clipping a fingernail. The next few weeks are spent bonding while slowly healing. Unity and strength in pain.

The Wound isn’t a tract arguing for or against this practice, thankfully. Indeed, Trengove doesn’t even focus on the initiates themselves. Instead, we view events through the eyes of Xolani (Nakhane Touré), a slightly older guy who’s already gone through the ritual and now sometimes returns to serve as a sort of mentor/drill sergeant, paired with one of the new kids. A wealthy businessman from Johannesburg specifically requests Xolani to toughen up his thoroughly Westernized son, Kwanda (Niza Jay Ncoyini), lest the boy’s addiction to iPhones and designer sneakers sap his tribal energy. Xolani agrees, but for a reason of his own—one that’s fraught with danger in this particular environment, with its unrelenting emphasis on ultra-traditional masculinity. (Apart from one brief crowd shot at the end, there are no women in the movie at all.) When Kwanda tumbles to what’s going on in secret between Xolani and Vija (Bongile Mantsai), one of the other mentors, he suddenly realizes that he may have some unexpected leverage.

To a certain extent, Trengove (who is white but who has clearly immersed himself in Xhosa culture; the film never feels like ethnographic tourism) has simply found a fascinating context for what’s otherwise a pretty conventional tale of the closet, subcategory “coming out could well be fatal.” But he has a potent weapon in Touré, whose superb, deeply internalized performance manages to suggest wellsprings of longing concealed by a scrim of perpetual wariness. The Wound excels so long as it hangs back a bit, watching Xolani struggle to project the authority that his role demands, despite being acutely aware of his own vulnerability. Only toward the end does Trengove (who cowrote the screenplay with Thando Mgqolozana and Malusi Bengu) succumb to narrative expectation, engineering a predictable finale that registers as more obligatory than deeply felt. It’s a forgivable lapse, especially given that this is his first time at bat. Just be sure to arrive at the theater about 10 minutes late if multiple penile lacerations (not graphically shown, but persuasively simulated by the actors and on the soundtrack) are more than you can stomach.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.