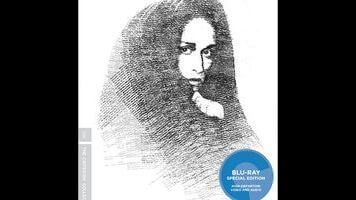

Novels that traffic heavily in metafiction present a unique set of problems when it comes to film adaptations. One option—the best, usually—is just to leave that material on the page, where it belongs; nobody has yet been foolish enough to make a movie of Nabokov’s Pale Fire, for which we all should be grateful. Another approach, employed by Philip Kaufman in his adaptation of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness Of Being, simply ignores the book’s experimental aspects, focusing exclusively on its narrative. Then there’s the riskiest and most potentially fruitful alternative: Invent a uniquely cinematic correlative to the author’s inherently literary playfulness. That’s what legendary playwright Harold Pinter boldly attempted in adapting John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman for the screen in 1981. (The film is being released on DVD and Blu-ray this week as part of the Criterion collection.) Pinter failed almost completely, alas, but his ambitious effort is still worth applauding. At least he tried.

To the extent that Fowles’ novel has a traditional story, it involves the romance between Sarah Woodruff (Meryl Streep), a disgraced woman living alone in 19th-century England, and Charles Smithson (Jeremy Irons), a gentleman who’s engaged to another (Lynsey Baxter). Encountering Sarah by chance one day on a jetty, where she frequently goes to stare out to sea and pine for the French lieutenant who jilted her, Charles develops an intense fascination at first sight with this profoundly sad woman, and proceeds to engineer further encounters with her. They fall in love, and Charles eventually decides to… well, that’s where the adaptation process gets a tad tricky. Throughout the book, its narrator—Fowles himself, presumably, though he’s never identified—interrupts to comment upon events. He winds up providing the reader with three completely different endings, giving them all equal weight. That’s far from the only metafictional touch in the book (which is first and foremost a symposium on the conventions of Victorian fiction, which Fowles at once faithfully replicates and repeatedly subverts), but it’s the most dramatic.

To his credit, Pinter understood that including literary devices like the narrator’s interjections and multiple endings in the movie wouldn’t translate well. Instead, he devised a bifurcated structure in which the relationship between Sarah and Charles is mirrored by the relationship between the two actors playing them in (essentially) the very movie we’re watching. This French Lieutenant’s Woman repeatedly interrupts the 19th-century tale for interludes, newly invented for the movie, in which Anna (Streep again) and Mike (Irons again), who are both married to other people, engage in an on-set affair during the shooting. There’s still a metatext, but it’s been wholly reconceived for the new medium.

That’s an exceedingly clever idea. Trouble is, Pinter never really figures out what to do with it, beyond its broad conception. For one thing, the two parts of the diptych are unbalanced: Until the last few minutes, Anna and Mike’s scenes are both infrequent and brief, making up only perhaps 15 percent of the film’s total running time. Nor does Pinter, despite being one of the 20th century’s greatest playwrights, succeed in making the contemporary characters more than cardboard ciphers. Their sole function is to serve as an ironic parallel to the main story—an ongoing compare/contrast exercise between Victorian decorum and modern-day philandering, with the juxtaposition suggesting that greater freedom doesn’t necessarily lead to greater happiness. Compared to Fowles’ intensive grappling with an extinct mode of expression, Pinter’s dual narrative is disappointingly superficial. At times, it could even be dismissed as merely cute.

What endures from this noble but failed experiment, three decades later, are its two central performances. Director Karel Reisz was never an especially formidable stylist, and his commitment to naturalism (derived from the Free Cinema movement of the ’60s) is all wrong for this project. But he was reliably strong with actors, from Albert Finney in Saturday Night And Sunday Morning (1960) to James Caan in The Gambler (1974). Here, he provides Streep, who’d won a Supporting Actress Oscar for Kramer Vs. Kramer two years earlier, with her first true leading role, and she makes the most of Sarah’s unusual amalgam of self-possession and neediness. Irons, for his part, had appeared in only one previous film (though he’d done a fair amount of work on British TV), yet he manages to command the screen while simultaneously conveying Charles’ tragic weakness of character. When the two of them are together in the frame, impassioned and torn, it’s possible to get temporarily swept up in the romance. But there is no romance in The French Lieutenant’s Woman, really. There never was. It’s like dramatizing a math equation.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.