Joy Williams’ Harrow is a strange, comic novel for the end of the world

In her first novel in over 20 years, Williams has written a philosophical story of climate change filled with weighty symbols

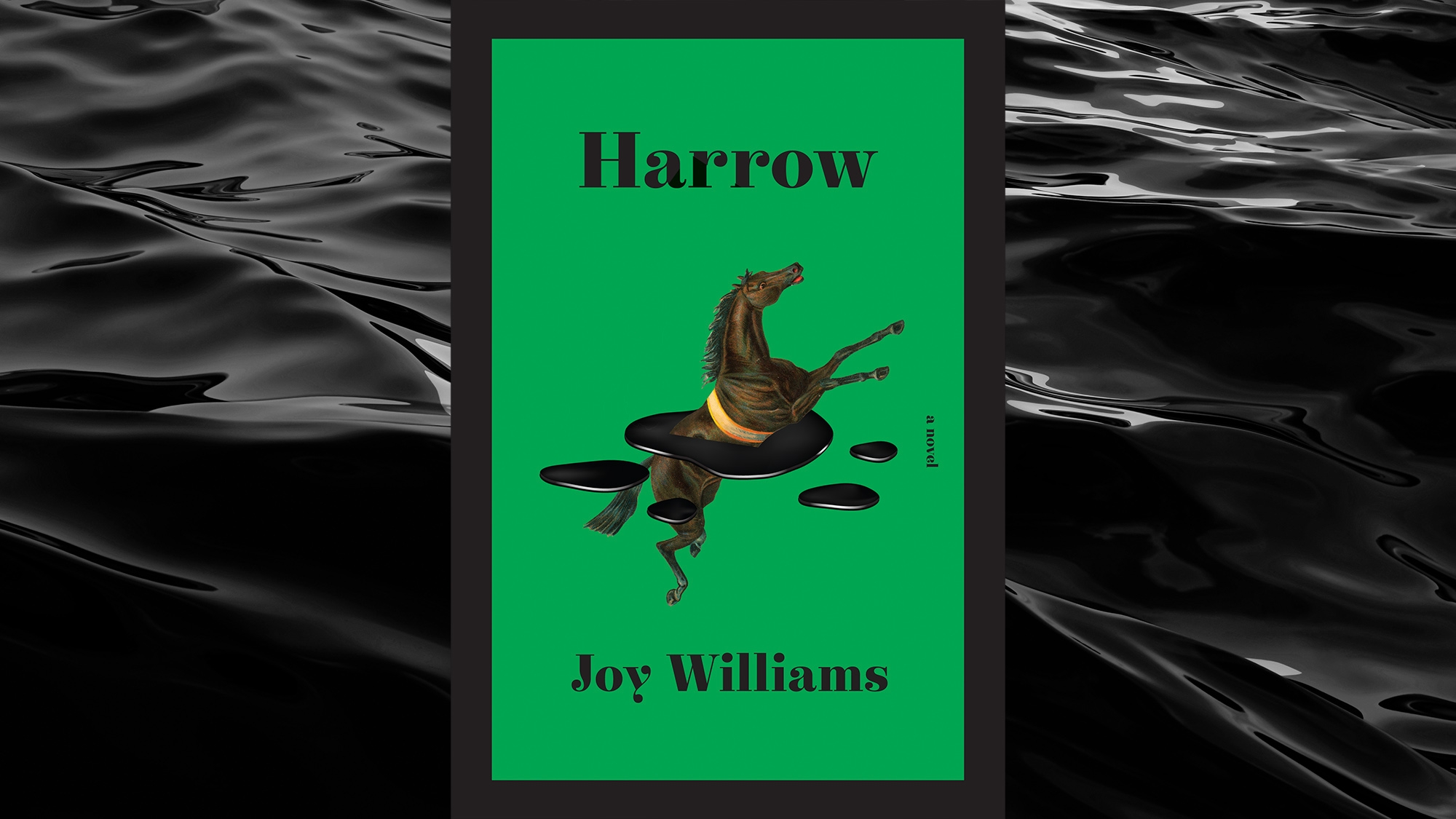

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Late in Harrow, Joy Williams’ first novel in over 20 years, one young character gives to another a little known Kafka short story to read and interpret in front of him. Both of them have been through some shit by this point—mostly the climate apocalypse, but also a few odd deaths of family members. The story, “The Hunter Gracchus,” concerns a man who has died and is cursed to wander the world without purpose. Life under climate change is akin to death, Harrow suggests, a purgatory where the dead roam the torn earth waiting for their second, actual deaths. But also, life is like this anyway always, climate change or not. Earlier, someone tells the teenage protagonist (who is said to have died as a baby and come back to life), “‘Your transience is so great that you do not exist.’” And so Williams placing the Kafka story where she does feels like someone handing over the keys to a house you’ve already broken into: Sure, it would have been more helpful earlier, but where would be the fun in that?

Harrow is about climate change the same way Twin Peaks is about who killed Laura Palmer. Its concerns—time, death, the afterlife—are more fundamental and eternal. The loose design of this strange and comic novel is something of a very slow picaresque, with the orphaned Khristen going to one place, then another, then one more. Simple survival often figures heavily in stories of the apocalypse, but nobody seems to need to eat in this book. The worry, if you can call it that, is existential. What to do with oneself? For the dozen or so terminally ill seniors at the crumbling old hotel called the Institute—where Khristen looks for her mother after her boarding school closes—the answer is eco-terrorism. Sort of. “The Institute was not a suicide academy or a terrorist hospice. Or not exactly,” Williams writes. Each resident is assigned someone in agriculture or a cruel animal scientist to take out, but nobody can get it together enough to go after the guys at the top or work with anything like efficiency. The oldsters are so ineffectual that some of their targets die of natural causes. By the time Khristen arrives at their outpost, the residents themselves are dying or being asked to leave.

Williams gestures toward plot, but there isn’t tension so much as stuff happening. At one point, one of the eco-terrorists gives a report on what the world outside the Institute is like: Most people think the earth has turned against them, and conservation efforts are considered reactionary. Another author would include this expository dialogue on page seven; Williams sticks it in halfway. As with her previous novel, 2000’s Pulitzer finalist The Quick And The Dead, the writer doesn’t build up to an ecstatic narrative peak; rather, a climax materializes by way of a meditative conversation between two people who are better versed in philosophy and literature than the average citizen.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.