“Why do you trust me?” “I distrust you the least.”

“I don’t wanna sit around with my thumb up my ass playing catchup.” “You worry like a bitch.”

“You know him—caffeine and cooze.”

“Have you seen my ass? I just got it chewed clean off.” “And I’ll close this before your balls end up on the mayor’s mantle. Right next to your ass.”

“Prove you’re clean!” “I can’t prove anything beyond my word!” “And we know what that’s worth!”

“His father was obedient like a dog, but he is… rebellious.”

“Brendan’s stink is on me and I don’t know how much.”

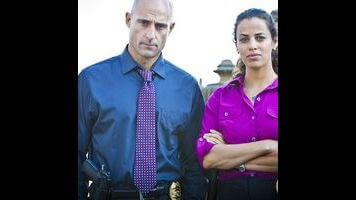

It’s an overused quote (and Mark Twain was waxing sexist when he said it) but Twain’s observation about women and profanity, “She has the words but not the music,” keeps coming to me the more I watch Low Winter Sun. The quotes above, all taken from the third episode, “No Rounds,” are a perfect illustration of Twain’s point. They’re lousy lines, sure, but their real crime is that they are indifferently lousy lines. And no one in Low Winter Sun seems to actually have any investment in speaking them. Even in the hands of a decent cast, the series continues to look and feel distinctly uninhabited.

Take the pre-title sequence tonight: In the last episode, Lennie James’ Joe confessed to Mark Strong’s Frank that Joe defied his dirty-cop partner Brendan and did not kill Frank’s hooker girlfriend Katia, but instead drove her across the border to Canada and told her to disappear. Tonight we see, in flashback, that exact scene—Joe defies Brendan’s order to kill Frank’s hooker girlfriend Katia and instead drives her across the border to Canada, where he tells her to disappear. Coming to from his reverie in a church pew, Joe looks up at the crucified Jesus and murmurs, “I should have killed her.” Because that’s what he’s thinking. That he should have killed her.

It’s a recurring fault of the show that everyone seems to be on rails, dramatically speaking. Sure, there are a few twists and turns along the way, but nothing so dramatic that the characters can’t just lean into them, or that the audience can’t see coming from a long way off. When Joe, under the duress of a serious ass-kicking administered by Frank at the end of the last episode, tells his story about what actually happened to Katia, there is at least some dramatic tension in the possibility that he’s lying. After all, Joe roped Frank into killing Brendan under false pretenses in order to cover up his part in his and his partner’s dirty doings, setting up a situation where it seems he and Frank will constantly be circling each other distrustfully, even as they are drawn deeper together by the ensuing investigation. Instead, tonight’s episode plunks down an unambiguous verification of Joe’s story, effectively cutting off that avenue of intrigue altogether. Sure, Joe still seems to be hiding things from Frank, but their conflict now has become essentially external, and far less interesting.

Invoking other, better shows like The Wire and Breaking Bad in last week’s review, I conceded that it was unfair to compare a fledgeling show like Low Winter Sun to such exemplars of the new TV model, and that remains true. I’d feel worse about it if the show didn’t continually keep dropping echoes of those shows (which its creators would clearly like to emulate) throughout. Tonight’s cop wake for the fallen Brendan is strikingly similar to the ones that punctuated The Wire—only Low Winter Sun’s rituals and speeches feel contrived while The Wire’s seemed lived-in and specific. That tinny, half-imagined aspect permeates the scene, culminating when Frank and Joe have one of those “we’re talking about something out loud, but the secret looks we give each other show we know what we’re really talking about” arguments about Brendan. The dramatic irony, as Frank rails against Brendan’s corruption, concluding “he deserved prison, but he didn’t deserve this” as Joe looks on, should be a big moment, but it simply doesn’t play. Mark Strong’s delivery is fine, but the fact that everything Frank says comes in the same clenched, soft-spoken intonation flattens the character with every passing episode. And the real problem, here as in elsewhere, is that Low Winter Sun is all text—handsomely-mounted, conscientiously-written, prosaic text—without subtext. Frank says exactly what he thinks here, he says it earnestly, and, if Joe sees there’s another level to his speech, well, so do we.

Meanwhile, the plot plods along. Internal Affairs (embodied, with a welcome light touch despite his hackneyed lines by live-eyed David Costabile) is snooping around Brendan’s murder and probing Joe’s possible involvement. Frank, playing both sides of the line, is still in charge of investigating his own crime while trying to keep Joe and himself from being implicated. Frank and Joe are really bad at hiding what they’re up to. Frank tells his commander they need to keep an eye on Joe while Frank investigates. Then Frank immediately goes into the other room—where everyone including his boss can see him—and has an intense conversation with Joe about their plans to subvert the investigation. The same thing happens over and over—Frank and Joe talk to an outsider, then huddle up about 10 feet away and growl out their interpretation of what the new information means for their deepening criminal conspiracy.

Oh, and in the barely connected B-story, James Ransone’s Damon and his deeply uninteresting crew hurry to get their combination drug/whorehouse up and running. There’s also a sub-sub-plot about troubled Afghanistan vet Billy Lush who has a backstory with Damon, and is befriended by Damon’s tough-cookie bartender wife Sprague Grayden, who has unexplained ties to sinister Detroit kingpin Skelos, and so on. Again, it’s not that there’s too much plot, per se—it’s that it’s hard to become invested when that plot is so indifferently laid out. That these two plot strands are so tenuously connected wouldn’t matter so much if we cared, at all, about what was driving the players. Especially Frank.

From the outset, Frank is simply too innocent for his character to be realistic—or interesting. He was a cop sleeping with a hooker, sure—but their relationship appears to have been ridiculously cuddly, and his understanding of her and her world impossibly naïve, at least from the flashbacks we see. And now, he looks down on Joe for “being on the payroll” of a local mobster with high-minded self-righteous contempt which immediately marks him as “the good cop,” his confession of having accepted “a couple of C-notes 10 years ago” notwithstanding. Yes, Frank’s role is as the decent cop pulled deeper and deeper into a web of deceit, etc, but Low Winter Sun keeps ironing out all his wrinkles—clean and starched and fresh, and about as compelling.

Stray observations:

- The opening scene, with Brendan sawing off a guy’s hands in a tub and a bound and gagged Katia begging for her life is the sort of “wham” opening that Breaking Bad pulls off with great impact. Here, however, it just plays as sordid and crude.

- Note to directors of boxing scenes: Shooting a fighter throwing punches directly at the camera will never not look silly. (Even in Silence Of The Lambs.)

- Low Winter Sun’s attempts to inject local color into its Detroit setting continue to fairly groan with effort. Tonight’s running gag about the feuding American and Lafayette Coney hot-dog establishments falls particularly flat. See “words vs. music” above.

- The same goes for the term “blind pig” which Damon’s crew utters seemingly in every third sentence to describe their abandoned house/den of sin. While the term (derived from speakeasies) could conceivably be cool, Detroit drug-guy lingo, I don’t for a second believe it coming out of these actors’ mouths.

- When Frank snuck into Katia’s house and eventually burned it down in the last episode, he had to worry about neighbors, fences, and a gate. Now, when he revisits the site, the burned-out hulk appears to be plunked down in the middle of a field. Lazy.

- Described as “a little rough,” an eyewitness to Brendan’s murder turns out to be the most articulate and thorough witness in TV history, complete with colorful exposition about the decline of the Detroit steel and auto industries.

- And, wait—they had the resources and time to put up chandeliers in the blind pig?

- The scenes where Mark Strong and Lennie James are most affecting (Frank goads a young fighter into beating him up, Joe flirts playfully with his bartendress) have the least to do with the plot. Given space to just be, they seem almost human.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.