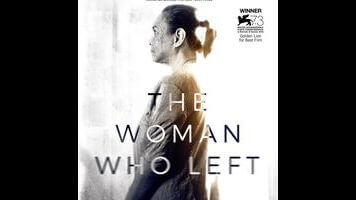

Set during the summer of 1997, The Woman Who Left largely centers on Horacia Somorostro (Charo Santos-Concio, a media personality strikingly cast against type), a middle-aged woman who has spent 30 years in prison for a crime she didn’t commit. A den mother and tutor to her fellow prisoners and the daughters they’ve raised behind bars, she is shocked when her closest friend in the penitentiary, Petra (Shamaine Centenera-Buencamino), abruptly confesses to having perpetrated the murder that got Horacia her life sentence, at the behest of Horacia’s then-boyfriend, Rodrigo Trinidad (Michael De Mesa). Swiftly exonerated and released, Horacia discovers that her now-grown daughter wants little to do with her and that her son has long since disappeared, and so makes her way to the city, where she begins to lead a double life that ingeniously parallels her mixed feelings about what has happened. Wearing long-sleeved sweaters to hide the prison tattoos that cover her arms, she spends her days helping those who are now less fortunate than herself. But by night, she dons a cap and ragged army jacket to prowl, falling in with the local street characters as she makes tenuous steps toward exacting revenge on Rodrigo, who is now a powerful local gangster.

Technically, the title refers to both Horacia and the film’s secondary protagonist, Hollanda (John Lloyd Cruz, another Filipino celebrity cast against type), an epileptic trans sex worker who is introduced about an hour into the film, and whom Horacia ends up taking in and nursing back to health after she is raped by a gang. As in Diaz’s Dostoevsky takeoff Norte, The End Of History—the first of his films to be distributed in the United States, with The Woman Who Left being the second—the film draws inspiration from classic Russian literature, in this case the Leo Tolstoy short story “God Sees The Truth, But Waits.” But that allegory about a saintly prisoner in Siberia only provides The Woman Who Left with a premise, with the richly conceived relationship between Horacia and Hollanda serving as Diaz’s own, extended Tolstoy-esque parable about cycles of violence and kindness. Its cosmically ambiguous and suggestive conclusion, which throws a subtle shadow over the whole film, is one reason a viewer might be inclined to forgive some of The Woman Who Left’s more trying stretches. The other is that sense of mundane wonder that Diaz sometimes elicits.

He has a peculiar eye. Although Diaz usually plants the camera far away from the actors, he studiously avoids compositions that suggest boxes or cages. His shots are off-balance, their horizontal and vertical lines subtly skewed, rarely parallel to the border of the frame. Combined with the dearth of continuity in most of his movies (i.e., every shot is its own individual scene), this ensures that one never learns how to speed-read his scene-long shots. While The Woman Who Left may not be as handsome or technically accomplished as Norte or as picturesque as the recent eight-hour A Lullaby To The Sorrowful Mystery (also starring Cruz), it has moments that deliver the platonic ideal of the arthouse long take—say, Horacia and Hollanda warbling through impromptu renditions of “Sunrise Sunset” from Fiddler On The Roof and “Somewhere” from West Side Story or a minute-long shot of Horacia walking down a country road through what one presumes is a very real downpour, based on the film’s budgetary constraints. In the most striking example, Diaz films one of the movie’s most dramatically important scenes out of focus, with Horacia only coming into sharp definition as she walks away, toward the camera, having realized what has happened. As with all of his work, these sequences take patience, developing deeper or more evocative meaning through duration.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.