Singing like she never has before, Jenny Lewis puts it all On The Line

Nobody would ever accuse Jenny Lewis of being circumspect. The catalog of her first band, ’00s indie-pop pace-setters Rilo Kiley, zeroed in on twentysomething emotional turbulence—the kind of tumult driven by ennui and loneliness intersecting with the euphoria of adulthood—with pinpoint accuracy. Her solo albums, especially 2006’s warm, country-leaning Rabbit Fur Coat and 2014’s kaleidoscopic rock outing The Voyager, were similarly pointed. Yet despite this veneer of vulnerability, Lewis excelled at preserving her own personal mystery. Thanks to coy (and wry) vocal mannerisms and blurred narrative perspectives, she achieved the delicate balance of appearing deeply confessional, while never giving everything away.

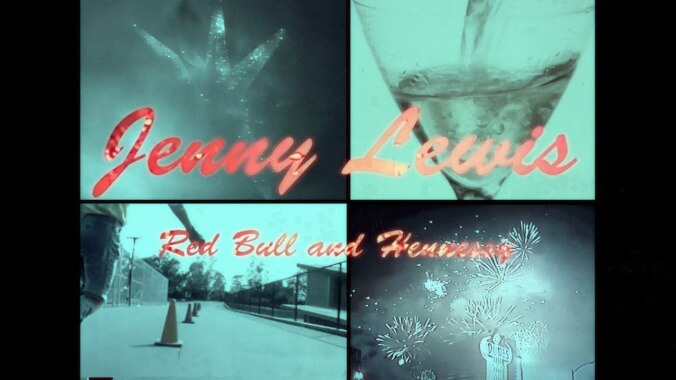

That’s changed with her probing fourth solo album, the slow-burning On The Line. Lewis has spoken candidly in recent interviews about how the death of her once-estranged mom and the dissolution of her 12-year relationship with Johnathan Rice cast a long shadow over the record’s multi-year genesis. And while these seismic events still filter into her lyrics in abstract and fanciful ways, as if refracted by a prism, she is more direct about the literal and figurative trauma wrought by this havoc. The protagonists of her songs overdo it on booze and bad decisions, go on mischievous adventures with mysterious characters (including a “narcoleptic poet from Duluth”), and have tearful and acrimonious fights. Throw in a smattering of pop culture nods (i.e., Candy Crush, Elliott Smith, crying like Meryl Streep), along with a woozy grasp on time and space, and On The Line feels dosed with faint mists of magical realism.

The most noticeable (and intriguing) difference between this album and the rest of Lewis’ catalog is how she sings about this chaos. That’s largely because of her studio approach this time around: She cut most of her vocals live, and often did so while playing along with her band on the same baby grand Carole King used on her iconic ’70s folk-pop LP Tapestry. “I am a better singer when I am playing an instrument in the studio,” Lewis said. “Less in my head. Less of a showboat. It’s like it erases all the child actor perfection shit that I learned as a kid.” This led to glorious, illuminating musical details; for example, on the title track, her pounding piano chords march in lockstep with the line “Whenever things get complicated, you run away to Mexico.” However, Lewis has also emerged as a more unselfconscious, chameleonic vocalist: She dips and croons, trying on vocal tones—a soapy falsetto here, sophisticated belting there, cheeky vibrato elsewhere—like someone let loose in a vintage costume store to slip on outfits.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.