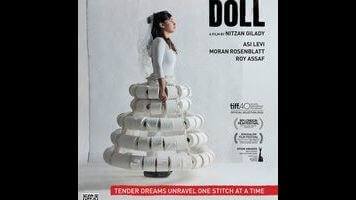

An artfully made drama with a suffocatingly negative view of humanity, the Israeli feature Wedding Doll describes a particularly circumscribed existence amid the lonely wastes of the Negev desert. Hagit (Moran Rosenblatt), an intellectually disabled 24-year-old who lives with her mother Sara (Assi Levy), dreams of a life of her own. But the daughter can’t always control her feelings of anger and disappointment, much less go outside without getting rattled by the taunts of kids half her age. So it’s at least understandable why her mother, who refuses to consider the assisted-living option for her child, has grown overprotective.

In order to underscore his characters’ cloistered routines, writer-director Nitzan Giladi and cinematographer Roi Rot keep the camera mostly static, even as Hagit is at her most industrious. The opening sequence of the film, a collection of extreme close-ups on handled-with-care craft supplies, shows the protagonist at her desk making miniature bridal figurines. Portrayed here as a kind of age-of-Etsy outsider artist, Hagit makes the dolls out of materials from the toilet-paper factory where she works—her most regular escape from home.

On the job, Hagit also moons over Omri (Roy Assaf), the son of the family that owns the operation, who has secretly strung along her hopes of being a bride herself. The well-intended young man seems to genuinely love his colleague. But that he’s also hesitant to stand up for Hagit in front of his friends, who make fun of her mercilessly, shows that he hasn’t really thought the whole marriage thing through. It’s clear enough from the outset that things are headed toward tragedy: Omri and Hagit rendezvous after work at what looks like the most precarious perch possible—they sit and kiss on the edge of a cliff overlooking a vast valley of sand.

Rosenblatt, who won a Best Actress award from the Israeli Film Academy for her performance, makes Hagit’s desire for a conventional life into something suitably affecting, a yearning that’s palpable in the character’s every nervous smile. And as divorced-mother-of-two Sara, who’s constantly canceling plans because she “can’t find a solution” for her grown-up child (as the film’s subtitles render it), Levy believably conveys weary resignation. But as the film moves along, pondering the fate of familial love in a society all too quick to cast out “weirdos” and “retards” (to cite two epithets hurled Hagit’s way), even the leads can’t keep it from feeling contrived. In spite of all Wedding Doll’s strengths, its scenario comes to seem a little unseemly: Giladi establishes Hagit’s hopes and dreams mostly just to show the terrible ways that they’re dashed.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.