Clue: Candlestick turns a board game into comic book brilliance

Adaptations are tricky endeavors, pulling stories out of their original media and forcing them into new confines that can often jeopardize their integrity. The challenge is heightened when that source material is a game. Video game adaptations are common and rarely pan out well, with filmmakers simplifying long, interactive stories to create bland, passive viewing experiences. The board game adaptation is far rarer, and while these properties are regularly optioned by Hollywood studios, few make it to production. 2012’s Battleship and 2014’s Ouija have quickly been forgotten, but one board game adaptation has stood the test of time and become a beloved cult classic: 1985’s Clue. That film revealed the creative potential of the murder mystery board game, and Dash Shaw further explores that potential in the pages of IDW’s new Clue: Candlestick miniseries.

In the past year, IDW has released some exceptional licensed comics by cartoonists who write, draw, color, and letter the books on their own. After blowing readers away with his wild Transformers Vs. G.I. Joe miniseries, Tom Scioli returned to transforming vehicles for Go-Bots, crafting a sci-fi horror story that expands the Transformers rip-off in fascinating ways. Copra’s Michel Fiffe recently wrapped up his tribute to Larry Hama’s G.I. Joe stories in the G.I. Joe: Sierra Muerte miniseries, an exhilarating action extravaganza served with a dash of political commentary. Shaw has never worked on a licensed comic before, and his alt-comics background makes him a surprising choice for IDW’s Clue: Candlestick miniseries. His unconventional plotting and expressionistic visuals bring new psychological dimensions to the Clue narrative, inviting reader interpretation to make up for the loss of the interactive game element.

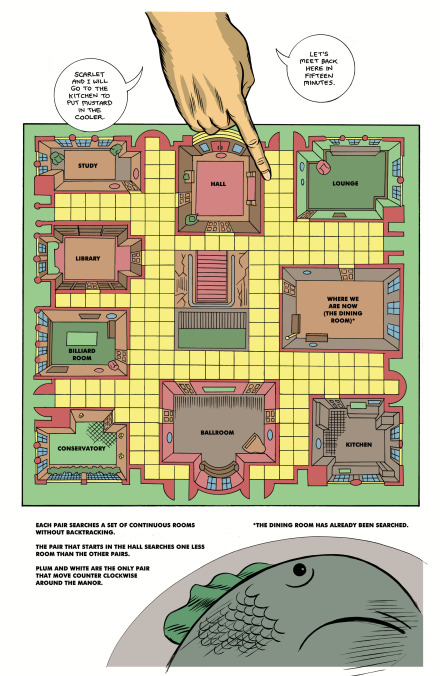

2017’s Clue by writer Paul Allor and artist Nelson Daniel was IDW’s first shot at adapting the board game for comics, and while it was a fun book, it primarily used the source material for narrative elements—characters, weapons, locations—rather than translating the game’s mechanics and the experience of playing it. Shaw makes a comic about the board game, incorporating the map, the game pieces, and a set of rules. He quickly puts readers in an investigative mindset by showing them the world through the eyes of Professor Plum, who scans objects, people, and spaces to gather minute details. Paranoia takes over when the point of view switches over to Colonel Mustard, a former special forces member living under a new name and in constant fear of discovery. Mustard follows every eyeline in a room, much like how Clue players are keeping watch of the people around them to determine who has which cards.

From the very start, Shaw establishes that this is a psychological drama by elegantly visualizing Professor Plum’s thoughts. A pair of lips appear outside of his window as he hears the whistle of the wind, and in a particularly striking panel, Shaw shows the wind traveling through a dense maze to Plum’s ears. Shaw takes a simple action and turns it into a complex image that puts the reader inside the character’s head.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.