Mary Elizabeth Winstead stars as Mary Phinney, a crusading Northern nurse who comes to Alexandria intending to spread the gospel of abolitionism, while also bringing modern medical knowledge to improve the conditions for the Union wounded. Almost as soon as Mary arrives, she develops a tricky relationship with one of the hospital’s doctors, Jed Foster (played by Josh Radnor), who also favors the latest scientific knowledge, but whose childhood on a Maryland plantation has left him with mixed feelings toward his new nurse’s pet causes. He has more sympathy for Emma Green (Hannah James), a Southern belle who volunteers at the hospital in order to make sure that Confederate soldiers are properly cared for—but also to escape the contentious atmosphere at home, where her firebrand brother James Jr. (Brad Koed) seethes at her furniture magnate father James Sr. (Gary Cole) for adapting so easily to the occupation.

Mercy Street’s most interesting character is Samuel Diggs (McKinley Belcher III), a black orderly who deals daily with threats from native Alexandrians who are sure that he’s an escaped slave, and distrust from co-workers who question where he picked up the surgical skill he sometimes shows off surreptitiously. Samuel’s story dissipates as the show packs in characters and subplots. Over the course of its six episodes, Mercy Street deals with Dr. Foster’s troubled marriage, his shaky sobriety, and his battles with colleagues (played by Norbert Leo Butz and Peter Gerety) over his attempts to treat a form of post-traumatic stress disorder he calls “soldier’s heart.” Meanwhile, Mary clashes with her fellow nurses who resent her ideas on proper nutrition and ward ventilation, James Sr. riles up his friends by putting ex-slaves to work in his factory, and an underground organization plots to kill a visiting President Lincoln.

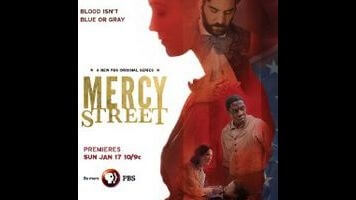

That’s a lot of ground to cover. And nearly all of it comes off as contrived. Mercy Street offers a mishmash of standard-issue medical drama storylines and self-conscious attempts to tackle the social issues of the 1860s. For the most part the performances are stiffly formal, marred by bad Southern accents and the cast’s inability to make lines like “Blood is not gray or blue, madam” sound natural. (To be fair, that’s kind of an impossible task to begin with.) The Downton Abbey influence isn’t just evident in the period setting and class conflict, but also in the general indifference toward artificiality. In Downton, the exaggerated soapiness is part of the charm (sometimes). Here, it feels more like a misjudgment in tone.

That sense that something’s off has a lot to do with the subject matter. When one of the core narrative elements of a series involves human slavery, it’s more noticeable when the creators try to play with the audience’s expectations of who the good guys and bad guys are. In a more sophisticated show—like, say, The Knick—Dr. Foster’s moral ambiguity and the Greens’ economic pragmatism would be a sign of strong, nuanced writing. In Mercy Street, where so many of the characters are either broadly villainous or heroic, softening the edges of former Southern slaveholders plays like an apologia.

Mercy Street is mostly just mediocre, not awful. It’s busy enough—and has an unusual enough premise—not to be boring. But co-creators Lisa Wolfinger (a documentarian by trade) and David Zabel (who ran the later seasons of ER) have said that they wanted to emphasize the gritty reality of war and surgery 150 years ago, and instead they’ve delivers a show that mainly just refers to that reality, without showing much of it. The costumes get bloody; the characters stay bloodless.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.