The jaw-dropping Little Bird takes a surreal approach to a familiar war story

It’s easy to question the intention of filmmakers who make the jump to comics. Are they passionate about the medium, or do they view comics as a way to develop intellectual property that can be adapted for film and television? There’s nothing inherently wrong with the latter, but it can often result in underwhelming titles that don’t take full advantage of comics’ vast creative opportunities. That isn’t the case with Image Comics’ Little Bird, filmmaker Darcy Van Poelgeest’s comic book debut, which follows a group of Canadian rebels fighting to take back their home from the theocratic United Nations of America. Van Poelgeest spent five years collaborating with artist Ian Bertram on this unsettling, exhilarating sci-fi miniseries, taking advantage of Bertram’s ingenuity and understanding of comic book craft to build a narrative that showcases the full range of the artist’s talent.

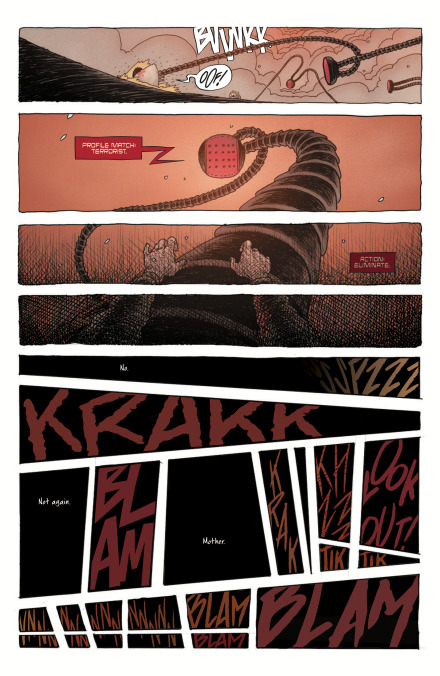

Bertram’s House Of Penance (2016) with writer Peter J. Tomasi is a paragon of comic book horror, establishing the artist as one of the most exciting visual thinkers in modern comics. His style is instantly recognizable with its flurry of small tic lines, which he adjusts to create different textures and control how the reader’s eye moves across the page and within individual panels. He’s capable of putting pretty much anything on the page. Little Bird demands a lot from him by mixing a sci-fi war story with a young girl’s surreal journey through her inherited trauma. Colorist Matt Hollingsworth, letterer Aditya Bidikar, and designer Ben Didier give the book a cohesive, distinctive visual identity, the strength of this art team elevating the story by bolstering its emotional content.

The premise of Little Bird isn’t too far off from We Stand On Guard, Brian K. Vaughan and Steve Skroce’s 2015 miniseries about the last line of Canadians standing against the United States’ northern expansion. But Little Bird balances the blunt, aggressive force of the military storyline with more introspective and poetic material, giving the book more interesting tonal dynamics that also allow the visual language to shift dramatically. Little Bird #1 takes readers to the Canadian wilderness and the New Vatican as it introduces the main players, but the book enters very different territory when the titular character is shot and killed.

The opening spread of Little Bird #2 is classic Bertram, a hauntingly beautiful image of Little Bird and her mother in the dream space between life and death. Intestine-like tendrils creep up toward the water’s surface and become the roots of a sprawling tree, uniting animal and plant to reinforce the connection between people and the earth. Panels of leaves falling through the air are arranged across the page in descending sequences, forcing the reader to slow down, while they also add a downward motion that accelerates over the course of the scene. The imagery gets even weirder from there, and when the two women leave the tree, they encounter a giant eye that gives Little Bird a look into her mother’s past.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.