The Mack remains one of blaxploitation’s most artistically ambitious films

Watch This offers movie recommendations inspired by new releases or premieres, or occasionally our own inscrutable whims. With the remake of the blaxploitation classic Super Fly opening in theaters this week, we’re looking back on the genre’s 1970s heyday.

The Mack (1973)

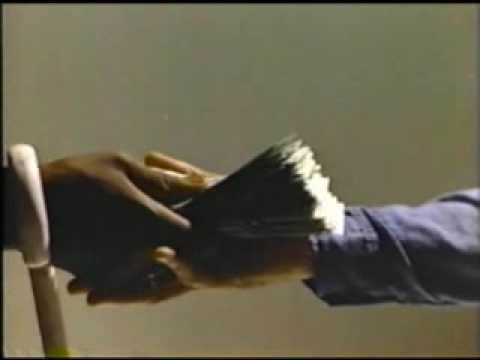

From its inception, The Mack had more on its mind than delivering a blaxploitation film, a label director Michael Campus always resisted. He shouldn’t have. His film is one of the finest examples of the genre, a smartly executed and deeply ambitious story of crime, corruption, and prostitution, shot on location in Oakland, California. But it’s clear where his hesitation with the term comes from: The film has its cake and eats it, too, deconstructing and offering social commentary on the genre it simultaneously performs with such deft style. The Mack provides the easy and retro pleasures of other entries in the “pimp film” sub-genre, like Super Fly and Dolemite, but its intellectual concerns and commitment to fusing it to a form of social realist cinema mark it more as the evolutionary sibling to Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, released just two years earlier.

On its surface, the storyline is pure escapism of the era. After spending five years in prison, small-time hustler John “Goldie” Mickens (the charismatic and classically trained theater actor Max Julien) returns to his Oakland stomping grounds determined to become the most successful pimp in the area, recruiting a bevy of women to oversee and acquiring all the clothing, cars, and accoutrements of the lifestyle. Eventually, his runaway success starts to run him afoul of other local gangsters, pimps, and the pair of corrupt cops who sent him to prison in the first place. Goldie has to decide whether to continue reigning as the best pimp around, or follow the lead of his brother, Olinga (Roger E. Mosley)—a black nationalist clearly meant to serve as the film’s mouthpiece for the Black Panthers—and renounce the underworld lifestyle that takes from his own people.

As with many of the great blaxploitation films, it was widely successful and embraced among black communities, and largely dismissed by white critics. (Vincent Canby’s New York Times review, with its snide assumption that, “I suspect the film isn’t even very honest about the profession it glorifies,” seems especially tone-deaf.) Part of what lends the film its sense of authenticity—an authenticity so accurate in its depiction of the stark bifurcation between underworld grit and glamor that it may explain why Canby found it borderline “surreal”—is how Campus and his production team managed to make the film in the actual neighborhood where the story takes place. As the director explained to The L.A. Times in 2013, in exchange for putting local pimp kingpin Frank Ward in the film, Ward allowed the movie to shoot on his turf, offered protection for cast and crew, and supplied all the real-life pimps, homeless people, and sex workers for the filming.