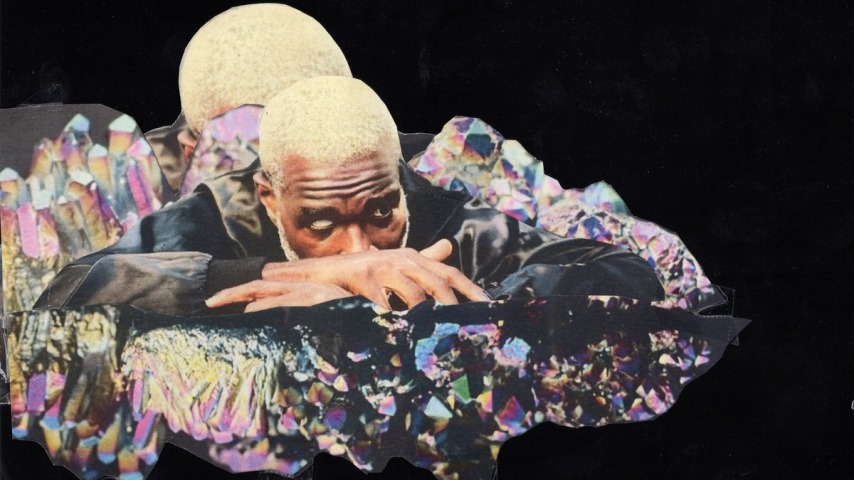

TV On The Radio, the kings of Brooklyn’s fertile art-rock scene of the 2000s, have brought an equally buzzing expansiveness to their finest work—from the slowly crescendoing wall-of-fuzz in “Halfway Home” to the haunted orchestral balladry of “Family Tree.” It’s all felt like the product of a capital-B band, one using every sound and experiment at their disposal to reach a grandeur they couldn’t on their own. When they’ve gently scaled things back, like the more patient stretches of their two most recent records, 2011’s Nine Types Of Light and 2014’s Seeds, the restraint was almost palpable. Adebimpe’s debut solo LP, Thee Black Boltz, feels even more deliberate in its modesty—none of its 11 songs reach the kaleidoscopic color or maximalist production of vintage TV. But that subtlety feels earned here, occasionally even enhancing the material’s naked emotion, which comes from a very real place.

Thee Black Boltz started germinating back in 2019, during a period of transition. TV On The Radio was on a break, and Adebimpe—an occasional director, here-and-there thespian, and early animator on MTV’s claymation cult-classic Celebrity Deathmatch—had largely pivoted into a legitimate acting career (Rachel Getting Married, Spider-Man: Homecoming, Search Party). Through the inescapable cloud of the pandemic and the immense grief of losing his sister (who died in 2021, at age 41, of a heart attack), the album gradually emerged. And a major turning point was connecting with Wilder Zoby (Run The Jewels), with whom he scored a particularly tricky episode of the PBS kids show City Island, then later set up a shared studio space. When Adebimpe landed his record deal with Sub Pop, he had the ideal collaborator in his Rolodex—a versatile co-writer, producer, and instrumentalist who helped bring vibrancy and levity to his often heart-wrenching songs.

The most direct and vulnerable of the bunch is “ILY,” a shockingly sparse ballad built on little more than a fingerpicked acoustic guitar and a flickering vocal harmony. “I love you / With a heart that’s pure and true,” he sings in tribute to his late sibling. “Came through the shadows / Like a beacon in the dark / Ever so grateful for the spark.” The paring-back here feels purposeful. But even some of the album’s frenetic moments feel similarly skeletal, like the springy “Ate The Moon,” highlighted by growling synth-bass and volcanic chorus fuzz. What the latter may gain in immediacy, it does lose in headphone-tailored awe—one can’t help but ponder, in the selfish way fans often do with their favorite artists-gone-solo, what some dynamic overdubs from the TV dudes could have brought out of the track. (Perhaps coincidentally, two of the album’s most breathtaking songs feature contributions from Adebimpe’s bandmate Jaleel Bunton: Lead single “Magnetic” is a pulsating, falsetto-laced shout-along, and “Pinstack” is a head-turning wild card, with a dusty Motown drum groove, a choral vocal break, and a chaotic guitar solo.) Eventually, though, you stop poring over the minutiae of production and arrangement, and stop comparing these songs to your expectations.

On the album’s centerpiece, “The Most,” Adebimpe elevates his reflections on a mutually beneficial breakup (“But I can’t waste my precious time / Hating on you, baby”) with a bent-note vocal hook and stuttering drum machines. It feels like Thee Black Boltz at its core: the artist laying bare his own angst through a catharsis that feels not bleak but euphoric.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.