It’s not quite what Alex Of Venice (set in Los Angeles, not Italy) has in mind, however. Alex still spends relatively little time with her kid, who gets passed off to her flaky visiting sister, Lily ( , one of the film’s three credited screenwriters). And while she’s concerned about her father (Don Johnson), an actor who lives with her and seems to be exhibiting the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, she doesn’t really interact much with him, either. Instead, she gets her groove back by tentatively pursuing other men—a big deal, for her, as her lifetime total of sexual partners currently stands at one. At first, she sets her sights on dorky co-worker Josh (Timm Sharp, who played Dougie on Enlightened), though Josh seems more interested in Lily after he sees her in a slinky dress. More successful is Alex’s rather blunt seduction of Frank (Derek Luke), who just happens to be the developer her firm is suing in an effort to prevent his proposed new health spa from wiping out Venice’s few remaining wetlands.

That trumped-up relationship—which predictably results in anger when one of them wins and the other loses, an eventuality that they somehow never seem to have considered—typifies Alex Of Venice’s clumsy screenplay, which also works overtime to underline its themes. Dialogue is reliably on-the-nose, and Alex even gives impassioned courtroom speeches that blatantly dovetail with her messy personal life. (“I find that really comforting—that no matter how out of control or tenuous life is, there are still some things that are forever,” she tells the judge, ostensibly talking about our natural resources but clearly reflecting upon the shards of her marriage.) And just in case anyone should still miss the point, her dad is appearing as Firs in a production of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, which is all about coming to terms with loss.

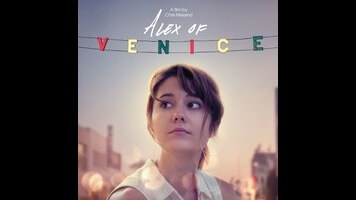

Still, the biggest problem with Alex Of Venice is that it’s kind of bland. Winstead is always an appealing screen presence, and she works hard to give Alex three dimensions; this isn’t as impressive a performance as her ambiguous turn in Faults earlier this year, but it’s still rich in emotional detail and devoid of affectation. (She has great sisterly rapport with Nehra, too, even though there’s no way those two women could have emerged from the same gene pool.) There’s just really nothing about this woman or her circumstances that merits an entire feature film devoted to her. Her marriage ends, she grieves, she rallies, she meets other guys, she goes to work, she vaguely remembers she has a kid, and life goes on. That’s about it, and Messina-the-director has no discernible passion about either the story or the medium. This is one of those movies that seems to exist solely because some people wanted to make a movie. That’s just insufficient.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.