Exclusive It's (Almost) Always Sunny In Philadelphia book excerpt reveals how creators sold the show with a VHS

Fox executives emphatically did not understand the pitch, according to Kimberly Potts' new book.

When It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia premiered in 2005, no one would have guessed that it would go on to become the longest-running live-action sitcom in American history. The series follows friends Mac (Rob McElhenney), Dennis (Glenn Howerton), Charlie (Charlie Day), and Dee (Kaitlin Olson), collectively known as “the Gang” (with the later addition of Danny DeVito’s Frank), as they run a dive bar in South Philadelphia. It’s less about the bar, though, and more about the Gang’s deranged interactions with each other and the outside world. The Gang is gleefully unlikable, they never learn or grow, and that’s the point.

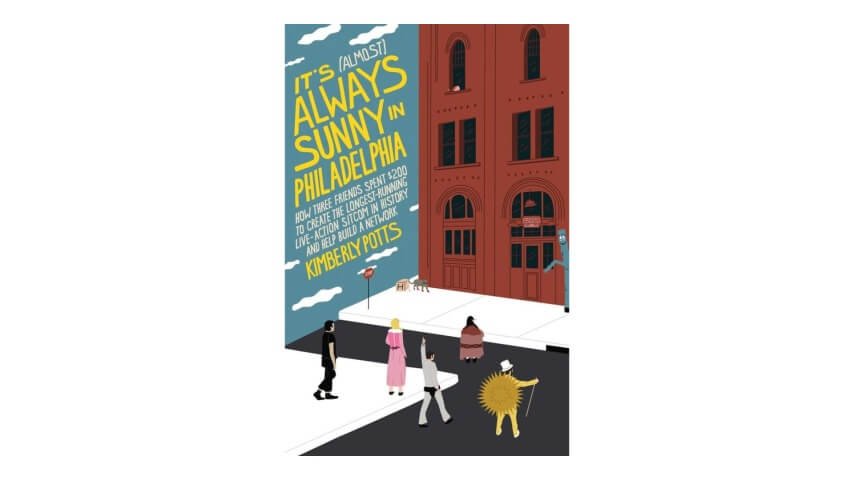

In her new book, It’s (Almost) Always Sunny In Philadelphia: How Three Friends Spent $200 To Create The Longest-Running Live-Action Sitcom In History And Help Build A Network (out July 1), Kimberly Potts traces the history of the show, from all the major networks passing on McElhenney, Howerton, and Day’s pitch to its unlikely success 20 years later. In this exclusive excerpt, Potts details how McElhenney sold the show with just a VHS tape and his uncanny charisma.

The whole project began with a dream and McElhenney’s ambition pushing his friends toward a creative endeavor, the results of which he now carried on a single VHS tape. He was ready for the pitch meetings Ari Greenburg had arranged, ready to show TV executives what he and his friends had done and could do. The VHS tape as the delivery method of their creativity was certainly not going to make anyone in an executive suite see the It’s Always Sunny on TV gang as fresh or cutting-edge, but it did have a well-thought-out purpose. Shiny silver DVDs, like the one holding the footage of the two Sunny shorts, copied directly from McElhenney’s laptop, had a nasty habit of randomly refusing to play in DVD players. McElhenney had seen it happen on his own with a disc of the Sunny shorts he’d burned as a screening for friends at Howerton’s apartment. Worst of all, he’d heard about such nonfunctioning DVDs ruining other Hollywood pitch sessions. Of all the things he could worry about going wrong at any of these meetings—though he was actually a confident, glass-half-full kinda guy by nature—a skipping or totally nonplaying DVD was not going to be one of them. Hence the VHS tape in its unlabeled original cardboard box, which he ferried to more than half a dozen meetings across a couple of days.

McElhenney had one objection to the idea of a pitch meeting: he didn’t want to have to pitch. He didn’t want to go into those network offices filled with television executives who thought they’d seen it all and try to persuade the skeptics that he and his inexperienced collaborators were going to bring something different to TV land. He and Howerton and Day made It’s Always Sunny on TV to show they had something special to offer. So McElhenney intended to simply insert the tape into the VCRs, hit play, and wait for the laughing to commence.

It was a brash decision for someone who was lucky to get such a lineup of networks interested in the first place. Twenty-five-year- old actors, with little writing experience, no credits as producers or showrunners, and deleted minor performances in two movies (The Devil’s Own and Wonder Boys) as their most impressive acting ré-sumé entries don’t usually/often/ever have the opportunity to sell their idea for a comedy series with no known cast members to MTV, VH1, Comedy Central, HBO, CBS, Fox, and FX, all in two short days. It was only the influence of Ari Greenburg that made those meetings happen.

Back in 2004, Greenburg, now the president of the William Morris Endeavor (WME) agency, was an Endeavor agent with an impressive track record of “packaging,” or putting together the elements of TV series. He helped make The Osbournes a seminal reality program for MTV, and was also responsible for Without a Trace, The O.C., Prison Break, and Veronica Mars—all series that became hits. Greenburg would go on to package dozens of other shows, including This Is Us, Heroes, Supernatural, Westworld, Riverdale, Once Upon a Time, Bob’s Burgers, Arrow, and The Flash, and set up huge deals for the likes of Dick Wolf and Greg Berlanti, two of TV’s most prolific producers.

Greenburg particularly connected with McElhenney on a personal level. Yes, he liked It’s Always Sunny on TV and thought it was a very funny show with a lot of potential. But he also, like McElhenney, grew up in Philadelphia, and they both had dreams of making it big in Hollywood but were seen as underdogs to do so.

When Greenburg began interviewing for jobs after his Berkeley graduation, he was excited to land a meeting with a human resources executive at International Creative Management (ICM), one of the industry’s biggest talent agencies. Greenburg’s ultimate goal was to run a broadcast television network, and he was certain a spot in ICM’s agent-training program would be an important first step to his dream destination as one of TV’s top decision-makers. But before he could make it through the interview, the executive shared a crushing opinion: Greenburg didn’t have the makings of a Hollywood agent.

Actually, that review would have crushed a less committed and ambitious young talent. Greenburg instead let it fuel him to become an agent at a different firm, working his way up from phone-answering assistant gigs to junior agent to TV packaging guru and all the way to president of WME. He saw that same kind of commitment and ambition and intelligence in his fellow Philadelphian, and that was a major factor in Greenburg’s decision to take McElhenney and his homemade pilot around town to network development executives.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.