The frailty comes easily, given that Lewis really is that old; almost everything else is a bromide. The best Max Rose offers are a few acrid touches: a master shot that lingers on the very sparse crowd at the funeral of the title character’s wife; hints of middle-class satire in way Max’s son (Kevin Pollak) struggles to find things to do with his aging father, vacuously reading descriptions off DVD cases and reciting Yelp star ratings for pizza parlors; a somewhat inspired sight gag that tracks Max’s time at a nursing home based on which alphabetically ordered Sue Grafton mystery novel he’s reading.

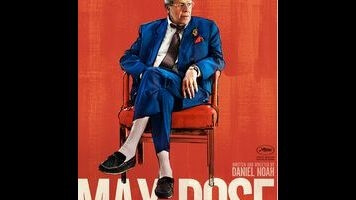

But these moments—as well as the creepiness of the first minutes of Max’s confrontation with the man he believes may have been his wife’s lover, staged in a moonlit bedroom—are canceled out by writer-director Daniel Noah’s artless regurgitation of assorted truisms about marriage and mortality. The premise is a fundamental loss: the death of a spouse, the emptying and sale of a home, the discovery of a locket inscription that suggests that both might not have had as sturdy a foundation as the fragile hero believed. But its effects—seen in part through Max’s relationship to his grown-up granddaughter, Annie (Kerry Bishé)—run the gamut from cloying to the vapid.

Perhaps it says something about Max Rose’s plodding pace (at a mere 83 minutes, it still feels too long) that the move to the nursing home—where Max, a former jazz pianist, befriends a trio of fellow old-timers (Mort Sahl, Lee Weaver, Rance Howard)—is the closest the movie comes to perking up. Noah has had success as an indie producer and he has the benefit of good casting here, but appears unable to visualize his way out of a paper bag. In one unfortunately typical sequence, Max struggles to use an electric can opener in student-film-grade handheld jump cuts while strings and piano plead for a viewer reaction—something, anything—on the soundtrack.

Lewis, who turned 90 this year, commits to Max’s thorniness and sense of loss, but doing the same appears to be beyond the capabilities of the film itself, which shuffles along to a “twist” straight out of Chicken Soup For The Soul before its inevitably inane coda. The real surprise, though, is that the film—alternately flat and murky in a way that hearkens back to the awkward early years of digital video—was shot by Christopher Blauvelt, Kelly Reichardt’s regular cinematographer.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.