Thing we were happiest to learn: One of the two wrote some legendary music on Brook Street. Handel composed no less than 28 operas, and 21 oratorios (including his best-known work, Messiah, famous for its “Hallelujah Chorus”), two dozen concert pieces (including “Water Music”), and countless smaller works. Hendrix was less inspired during his considerably shorter time there—after completing his own masterpiece, Electric Ladyland, his time on Brook Street was a down period during which the Experience broke up and Hendrix himself mostly stayed off the radar until his iconic performance at Woodstock.

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: It took 42 years to open the Handel House. Musicologist Stanley Sadie had the idea for the museum in 1959, at a party held there to commemorate the bicentennial of Handel’s death. It took 30 years for Sadie and his wife to set up the Handel House Trust, and another 12 of raising funds and collecting memorabilia before the museum was ready to open (which it did in 2001).

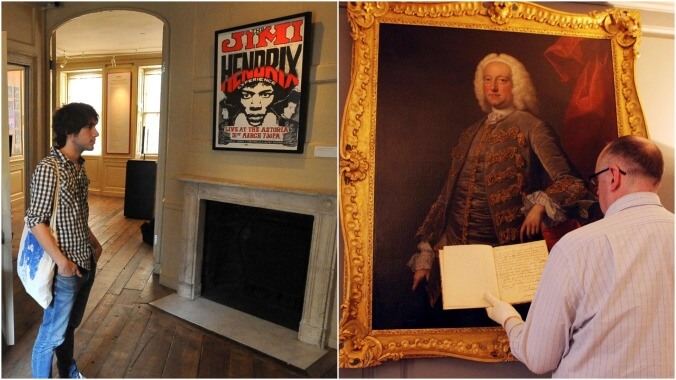

Also noteworthy: Perhaps reflecting the relative amount of time the two musicians spent on Brook Street, the museum still leans very heavily toward Handel. 25 Brook has been completely renovated in late 18th-century style, based on extensive notes taken upon Handel’s death on what furniture and instruments were in the house. The museum includes his original manuscripts, correspondence, contemporary paintings of Handel and some of his collaborators, and early editions of his operas and oratorios, some of which were rehearsed in the house. Wikipedia doesn’t mention any Hendrix memorabilia, or any work done to make 23 Brook Street late-’60s period-appropriate, although that may simply be an omission by the Wiki page.

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: When Handel was alive, his home contained several keyboard-based instruments, including a chamber organ, a harpsichord, and a clavichord. The latter two were quiet instruments made obsolete by the piano, which could be played softly or loudly (pianoforte literally translates to quiet-loud). But in the mid 1960s, the Hohner company electrified the clav, calling the new instrument the clavinet. Besides being amplified, it could be played through an effects pedal like a guitar. It took a while to catch on, but became a pop music staple in the 1970s after Stevie Wonder played it on his terrific cover of the Beatles’ “We Can Work It Out” in 1971, and Billy Preston used it on “Outa-Space” in that same year. Wonder would later use it for the iconic keyboard riffs on “Higher Ground,” “Superstition,” and “You Haven’t Done Nothin’,” and throughout the decade it would appear in everything from Captain And Tennille’s “Love Will Keep Us Together” to Herbie Hancock’s “Chameleon” to the Eagles’ “Life In The Fast Lane.”

Further Down the Wormhole: When Hendrix lived in London, London’s newest museum was the Hayward Gallery, a largely contemporary art museum notable for having neither a permanent collection nor government support, charging an entry fee to show an ever-changing slate of short-term exhibitions. The museum is located on the south bank of the Thames, in the borough of Lambeth. There’s a long list of people from the London borough of Lambeth, including William Blake, Davie Bowie, Charlie Chaplin, and W. Somerset Maugham. The neighborhood also boasts a few more infamous names, such as Shirley Pitts, the “queen of shoplifters,” who learned her trade from the Forty Elephants, an all-female crime syndicate that managed to operate from the 1870s through to the 1950s. We’ll take a look at their ill-gotten goods next week.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.