Adapted by Lelio and co-writer Rebecca Lenkiewicz from a novel by Naomi Alderman, Disobedience seems at first glance to share a basic premise with A Fantastic Woman, Lelio’s Oscar-winning drama about a trans woman trying to grieve her boyfriend’s death in a narrow-minded world. But the director is after something more even-handed, and though the rudiments of his direction remain sensual—a world of touch, forbidden and otherwise—its floweriness has been stripped away. In lieu of the earlier film’s dreamlike expressive effects, Disobedience puts an uncommon faith in concisions of acting and editing (including a wordless, believable montage of grief), and in loaded moments and changes in point of view that would probably play differently on a second viewing. It takes a substantial part of the film to figure out who is related to whom, and the mise-en-scène is so carefully repressed—beige and white walls, black clothes, the sheitel wigs under which Esti and other married Orthodox Jewish women hide their real hair—that Leilo’s few un-subtleties stick out sorely.

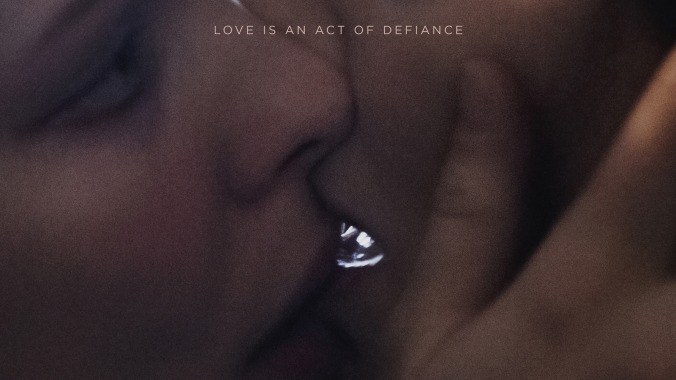

One would need to avoid seeing a single poster for the movie to not be able to figure where this is going: a sexual relationship between Esti and Ronnie that happened way back when, which remains enough of an open secret in the community that the sight of the two women alone would start rumors. But that’s all that’s worth spoiling, as a large part of Disobedience’s narrative pleasure lies in its handling of expectations and its three-dimensional characterizations of Ronnie, Esti, and Dovid. (The three lead actors all do fine work.) Unusually for a drama about suffocating social and emotional repression, Disobedience lavishes attention on religious concerns; it paints Dovid as a largely sympathetic character, a man in a spiritual crisis. But that’s essential to the film. Ultimately, it’s about mixed feelings, beginning with Ronnie’s own internal conflict: the need to lead a life of one’s own versus a grown child’s often painful love for their parent. Out of all the images in the movie, few are as sensual as the moment when she picks up and smells her father’s tobacco pipe while going through his belongings.

Nothing Rabbi Krushka left behind suggests that she ever existed (the local obituary even goes so far as to say that he had no children), and yet so much of her life is right here. But just as Disobedience takes its time getting there, it also takes it time to move on and to leave, languishing in repetitions and false endings. Plotting has never been a strong suit for Lelio, who made his name with character studies of unconventional women. Here, he tries his hand at something akin to classicism, and ends up mounting a compelling drama. Curiously, its main shortcoming parallels the human flaw that is its main theme: our yearning to leave often loses out to our inability to let go.