In our monthly book club, we discuss whatever we happen to be reading and ask everyone in the comments to do the same. What Are You Reading This Month?

In Skinship (August 17, Knopf), debut author Yoon Choi unfolds complex tales of first- and second-generation Korean Americans, weaving a rich tapestry of the diaspora. Choi’s characters aren’t always likable, and their stories are messy, complicated, and at times, downright heartbreaking. Like “First Language,” in which Sae-ri reveals to her arranged-marriage husband that she has a secret son back in Korea. When the son arrives in the States, he is sent away to a “a second chance ranch.” In “A Map Of The Simplified World,” Ji-won makes and then quickly loses her first American friendship at an elementary school in Queens. When Anjali—who contracts lice from an outbreak at school—is forced to cut her long hair, instead of supporting her friend during the worst parts of elementary school, Ji-won joins in on the teasing. In the title story, So-hyun and her brother skip school in order to flee their abusive father. Choi’s writing is expansive and descriptive, but also sharp and deliberate. Her stories are as multifaceted, thorny, and bittersweet as the immigrant experience itself. [Shanicka Anderson]

In her latest memoir, You Got Anything Stronger? (September 14, Harper Collins), Gabrielle Union takes readers on an exploration of Black motherhood. Union has been open about her miscarriages and struggle with infertility, and she adopts a similar approach when writing about her daughter, Kaavia James, who was born via surrogacy. She employs the same raw honesty when recalling her emotions of grief and loss and how difficult her miscarriages made it to embrace even the positive milestones in the surrogacy journey. In addition to highlighting her connection to her baby, Union shares details about her relationship with her mother and her stepchildren (dedicating a chapter to stepdaughter Zaya), and the maternal feelings she has towards her Bring It On character, Isis. As its name suggests, You Got Anything Stronger? isn’t an easy read. The book is an unflinching look at some harsh realities (and includes essays about the Black Lives Matter protests, America’s history of racial violence, and Union’s rape). But for all of her discussions of trauma, Union finds a way to include joy, too. She infuses her vulnerability with humor in a way that makes for an accessible and impactful read. [Shanicka Anderson]

Read The A.V. Club’s “They cheer and they lead: Bring It On ushered cheer culture into the mainstream.”

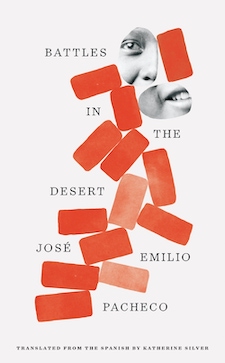

Battles In The Desert by José Emilio Pacheco (trans. by Katherine Silver)

Ever since its original publication in 1981, José Emilio Pacheco’s Battles In The Desert (June 1, New Directions) has been one of the most widely read novellas in Mexico. Part of this has to do with its inclusion in middle and high school curricula, which makes sense, as the novella captures an era of significant change in the history of the country. After Miguel Alemán’s election as president, in 1946, Mexico underwent rapid industrialization and urbanization, and saw an increase in economic disparities. Writing in this new edition’s afterword, Fernanda Melchor, the author of Hurricane Season, singles out Battles’ “impossible love” story as one of its main attractions. The narrator recalls how, as an adolescent, he falls in love with his friend’s mother; when his family and friends find out, his parents have him change schools and see a psychiatrist. I was most drawn to Pacheco’s portrayal of inequality and shifting social positions. In an early scene, the middle-class narrator, Carlos, is told by a more well-off American friend to improve his manners: “And don’t make so much noise with your soup, don’t talk with your mouth full, chew slowly, and take small bites.” At the end of the novella, when Carlos runs into an old classmate, whose family is so poor that he hasn’t had a meal in a day, he buys him a sandwich but is sickened to watch him eat it. The overlap is fitting of the story’s theme of lost youth—the way naked desire is made to be cast off for something that looks like growth. [Laura Adamczyk]

Read The A.V. Club’s review of Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.