10 episodes that highlight The Wonder Years' uncommon empathy

As the ABC series turns 35, let's shortlist the coming-of-age show's essential episodes

With TV Club 10, we point you toward the 10 episodes that best represent a TV series, classic or modern. They might not be the 10 best episodes, but they’re the 10 episodes that’ll help you understand what the show’s all about.

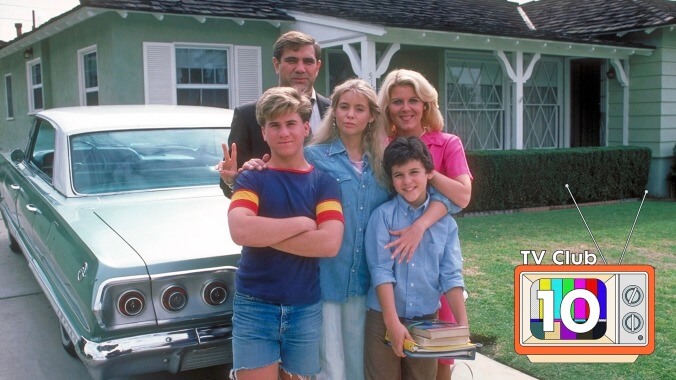

In 1988, at the end of the Reagan era, a modest show about growing up during the late-’60s debuted. The Wonder Years proved to be something special, epochal, and deeply empathetic in ways you just don’t see very much in this age of streaming. It was intimate. It was tender. It was, in other words, rare for a half-hour network program.

Kevin Arnold (Fred Savage) and his family live unremarkable lives in the suburbs, surrounded by people doing very much the same. They are content with their existence, dawdling behind the placid facade of American suburbia, with its a homogeneity of houses with trim green grass and boys playing ball in the street. But these are people who matter to the show’s writers, and they’re never denied dignity or internality. They may not have a lot and they may not rage against the machine (if they even acknowledge or recognize it). The show reflects not only the late-’60s—the rock ‘n’ roll, the hippies and homemakers, the tumult of the Vietnam War, the blooming of progressive ideologies—but also the late-’80s, at the apogee of Reagan’s popularity. Book banning was getting popular back then, just as episodes of this show rolled out. (With the way things have gone since, it wouldn’t be surprising if The Wonder Years got banned from schools, too.) And today, the genuine, unobtrusive progressiveness of The Wonder Years, and its uncommon empathy, feels almost radical 35 years later. (The show premiered January 31, 1988.)

But I don’t want to make you think this is ABC’s weekly liberal sermon: It is, deep down, in its thrumming heart, about being a boy—a boy in 1968, yes, but even more so about the intricacies and intimacies of boyhood. Think of school, which takes up half of your adolescence, and it sucks. There’s the barking of the gym teacher, the alluring sensitivity of the English teacher, the draconian principal, the raucous halls, the rampaging hormones of a 12-year-old. And there is, of course, his father, the first ideal of American masculinity of any boy’s life. Kevin tries out for the baseball team to earn the approval of his dad, and he’s terrible. (I relate to this. I sucked at baseball, even though I played from age eight to 18, but no matter what my mom was there.) And there’s also boyhood friendship: Kevin’s best friend is Paul (Josh Saviano), a four-eyed nerd who gets winded running down the street for the football and in whom Kevin finds the kind of dauntless loyalty and love that you only find as a kid. Kevin has other friends and acquaintances, most notably his once and always love, Winnie (Danica McKellar). Their first kiss at the end of the first episode is one of television’s most purely warm moments. Here and throughout the series (even as its glints of brilliance were far sparser later on), Kevin is sincere, reacting to a quarrel with Paul or a moment of intimacy with Winnie or the approval of a teacher he likes so much with the kind of awe and awkwardness and anxiety and adulation that any kid would.

And don’t forget Daniel Stern’s narration, offering reflections and observations on the events of each episode, articulating it all with the wisdom of age. It’s not entirely dissimilar to Scrubs, nor are Kevin’s occasional daydreams, his fleeting sparks of spectacle and fantasy. In the end, it’s Stern-as-Kevin who sums it up best: “If dreams and memories sometimes get confused, well, that’s as it should be. Because every kid deserves to be a hero. Every kid already is.”

“Pilot” (season one, episode one)

Kevin’s neighbor, the older brother of his childhood love Winnie, is killed in Vietnam, draping a veil of tragedy over the first season and creating some very real problems for a boy who can’t quite comprehend them yet. In the end of the show’s pilot, Kevin and Winnie share a kiss, the first for both of them, and it’s a stunning moment. The show was shot single-camera (whereas, say, Cheers was a multi-camera setup), and it is frequently lovely to look at. This episode, which has some simple, effective camera movements, was directed by Steve Miner, who made the second and third Friday The 13th films. And of all people, he establishes the show’s charming aesthetic quite well.

“Swingers” (season one, episode two)

This episode is about Winnie’s brother’s funeral and the day-after anxieties in the wake of Kevin and Winnie’s first kiss in the woods. (There’s a fantastic shot of blank pale headstones, arranged neatly in rows, the sameness and grid pattern recalling the homes these people lived in.) When Kevin’s mother tells him to bring Winnie some food, he suggests she try the ham, attempting incredibly hard to appear cool—and it’s oh-so-wonderfully genuine.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)