Documentary film often hopes to spark some passion in not only its audience but also its subjects. Whether it’s The Look Of Silence’s remorseless murderers being grilled by their old victim or Errol Morris’ multiple efforts to provoke new intellectual or emotional realizations in his man-alone character studies, there’s often an opportunity for reflection on the part of those whose lives are being analyzed. It doesn’t always happen (in the case of Morris’ The Unknown Known, about Donald Rumsfeld, it really didn’t happen), and it’s far from necessary. But it’s an appealing thought for directors, that they might end their feature-length investigations with some tangible evidence that the subject landed in a different place than where they began, the better to match the hoped-for journey of the viewer.

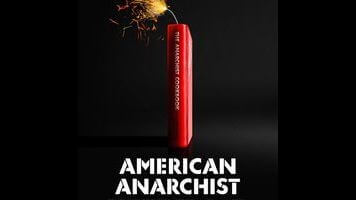

Unfortunately, you can’t force such a moment, and that’s where Charlie Siskel’s American Anarchist comes up short. The film’s subject is William Powell, the man who wrote the iconic how-to guide The Anarchist Cookbook, a cult text famous for promoting revolutionary overthrow of the powers that be and providing pragmatic blueprints for creating the weapons to do so, such as homemade dynamite. Powell penned the tract more than 40 years ago, when he was only 19. As director, Siskel (nephew of the late film critic Gene Siskel) is so single-mindedly intent on getting Powell to express a level of contrition or regret—one that he either doesn’t feel or won’t admit—that the back half of his film becomes a misguided scolding. Siskel’s unspoken “Say you’re sorry!” lingers over the majority of the final act, weighing the proceedings down so much that Powell is eventually forced to call it out himself, accusing the director of trying to coerce him into saying something he’s not saying. Powell’s right, and the last section of the movie recalls the scene in Bowling For Columbine (which Siskel produced) where Michael Moore shames an aged and ailing Charlton Heston, only with even less motive, as Powell has already given the director most of what he wants. (He’s given the world that, too: The author published an op-ed in The Guardian in 2013 denouncing The Anarchist Cookbook.)

It’s only thanks to Powell’s own rhetorical waffling that the movie succeeds to the degree it does. In an effort to pull the audience to his side, Siskel opens the film with some dodgy explanations from Powell. The author will read an excerpt from the Cookbook, then trip over himself trying to explain how he didn’t mean for people to use it in reprehensible ways. It makes him look culpable, and the film manages to wring some genuine pathos from this evasive introduction. We’re taken on a tour of Powell’s life, first through his coming to political consciousness at a young age and writing the notorious book, which contains such explosive information as bomb-making recipes. He experienced a brief burst of celebrity from publication of the tract and (by his own estimation) more than $40,000 in royalties, a not-inconsiderable sum at the time. However, he soon distanced himself from the book, becoming a teacher and dedicating his life to traveling the world and helping at-risk children, often in poor and needy communities and countries, about as close to a lifelong apologia via good works as can be envisioned. He and his wife, Orchan, live a quiet and remote life in France now, trying not to let the negative impact of Powell’s youthful radicalism haunt their present.

But what starts as an interesting look at a man who singularly inspired a lot of violent perpetrators becomes an unnecessarily hectoring judgment of someone who’s already been punished for his youthful bravado. (Powell has been denied numerous jobs throughout the years due to people republicizing his authorship of the Cookbook.) Time and again, Siskel cites school shootings, terroristic acts, and other tragedies in an effort to force Powell to say he’s somehow at fault. But as Orchan points out, her husband isn’t responsible for these deaths, at least not in any direct manner. He states repeatedly that he regrets making what was already publicly accessible information even more so, but that’s a far cry from having blood on his hands. In one interview, Powell makes an analogy to gun manufacturers and then immediately disavows it as a bad equivalence, despite it highlighting how his own contribution to violence is even less overt. Thanks to Siskel’s hectoring, those early shots of Powell equivocating start to look less like him ducking honest responses and more like someone who realizes a filmmaker is trying to shame him and doesn’t want to be painted like that.

To his credit, Siskel leaves in moments that suggest he’s tempered his views on Powell somewhat, such as Orchan accusing him of leading questions, and also a bittersweet postscript. But it rings disingenuous in the face of all that he leaves in. By film’s end, it’s Siskel, not Powell, who comes across as the misguided agent provocateur who might need to reconsider his position.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.