Sidney offers a portrait of Poitier's life and legacy that's only skin deep

Despite interviews with Spike Lee, Halle Berry, Morgan Freeman, and five of his children, too much of Poitier goes unexplored

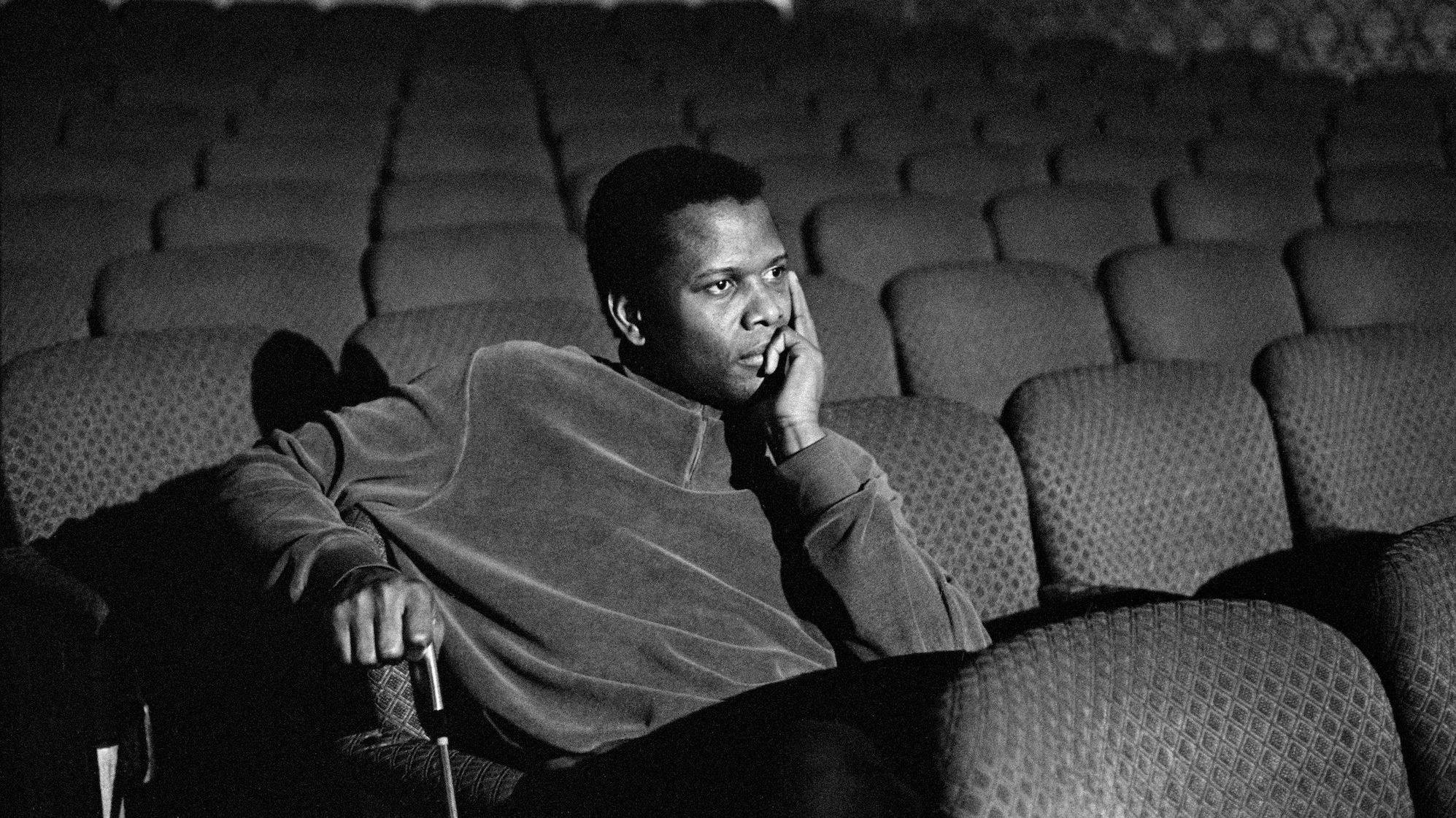

Sidney Poitier, who died in January at the age of 94, forever changed Hollywood—and the world in general. Suffice to say he’s worthy of a great documentary celebrating his life and legacy as an actor and activist, but in the meantime, there’s Sidney, a good, honorable but ultimately disappointing documentary from producer Oprah Winfrey and director Reginald Hudlin that begins streaming September 23 on AppleTV+.

Hudlin delivers a standard talking-heads documentary that’s more hagiographic than revelatory, which is a shame, as Poitier surely channeled some of his bitterness over racism, aspects of his complicated love life, etc., into his indelible performances in films like Blackboard Jungle, Lilies Of The Field, The Defiant Ones, Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, A Raisin In The Sun, To Sir, With Love, In The Heat Of The Night, and so on. Instead, we get a basic overview of Poitier’s rise to fame, told chronologically, with the likes of Winfrey, Denzel Washington, Lulu, Spike Lee, Halle Berry, Morgan Freeman, Louis Gossett Jr., Robert Redford, Barbra Streisand, biographer Aram Goudsouzia, historian Nelson George, Poitier’s ex-wife Juanita Hardy, and five of his six children commenting on the doors he opened for other performers of color. Also participating is Poitier himself, filmed in glorious close-ups, his voice as strong and distinguished as ever.

Poitier opens the film, noting “I believe that my life has had more than a few wonderful, indescribable turns,” before narrating his own story. Born poor in the Bahamas, but raised by loving, proud tomato farmer parents, Poitier explains that, early on, every experience, every modern convenience, was new to him—electricity, running water, even mirrors. After a harrowing run-in with the Ku Klux Klan in Florida, he made his way to Harlem, New York, where he worked odd jobs, was thrilled to see so many people who looked like him, and met a white Jewish waiter who taught him to read. Poitier recounts how the American Negro Theatre initially rejected him, and how he met Harry Belafonte, who would over decades become his friend, competition, co-star, and occasional sparring partner. Belafonte missed a play performance to work a shift at his job, and so his understudy—Poitier—stepped in, impressed the right person, and everything changed overnight. Interestingly, Belafonte did not sit for Hudlin, who relies on comments from others and archive joint interviews (notably with Dick Cavett) to include him in the narrative.

Sidney subsequently delves into Poitier’s remarkable career. He played a doctor in No Way Out (1950) and emerged as a leading man in The Defiant Ones (1958), opposite Tony Curtis. Much time is devoted to the latter film’s ending, in which Poitier’s character tries to help Curtis’ character and falls off a train in doing so, foregoing his shot at freedom. Thus was born the so-called “Magic Negro” trope that saw Black characters sacrificing themselves to help a white man. Belafonte turned down the low-budget drama Lilies Of The Field, which won Poitier an Oscar, only the second ever awarded to a Black performer, and the first since Hattie McDaniel decades earlier. By 1967, Poitier was even more of a star thanks to To Sir, With Love, In The Heat Of The Night, and Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.