Supernatural thriller The Perishing is a luminous love letter to Los Angeles

In consistently gorgeous prose, Natashia Deón rivals Nelson Algren’s Chicago: City On The Make when she writes about L.A.

Five years ago, Natashia Deón’s debut novel was named one of the best books of the year by The New York Times. Narrated by the ghost of a murdered slave, Grace slipped effortlessly between the past and the present, life and the afterlife. “Ms. Deón is not merely another new author to watch,” wrote Jennifer Senior in a rave review. “She has delivered something whole, and to be reckoned with, right now.”

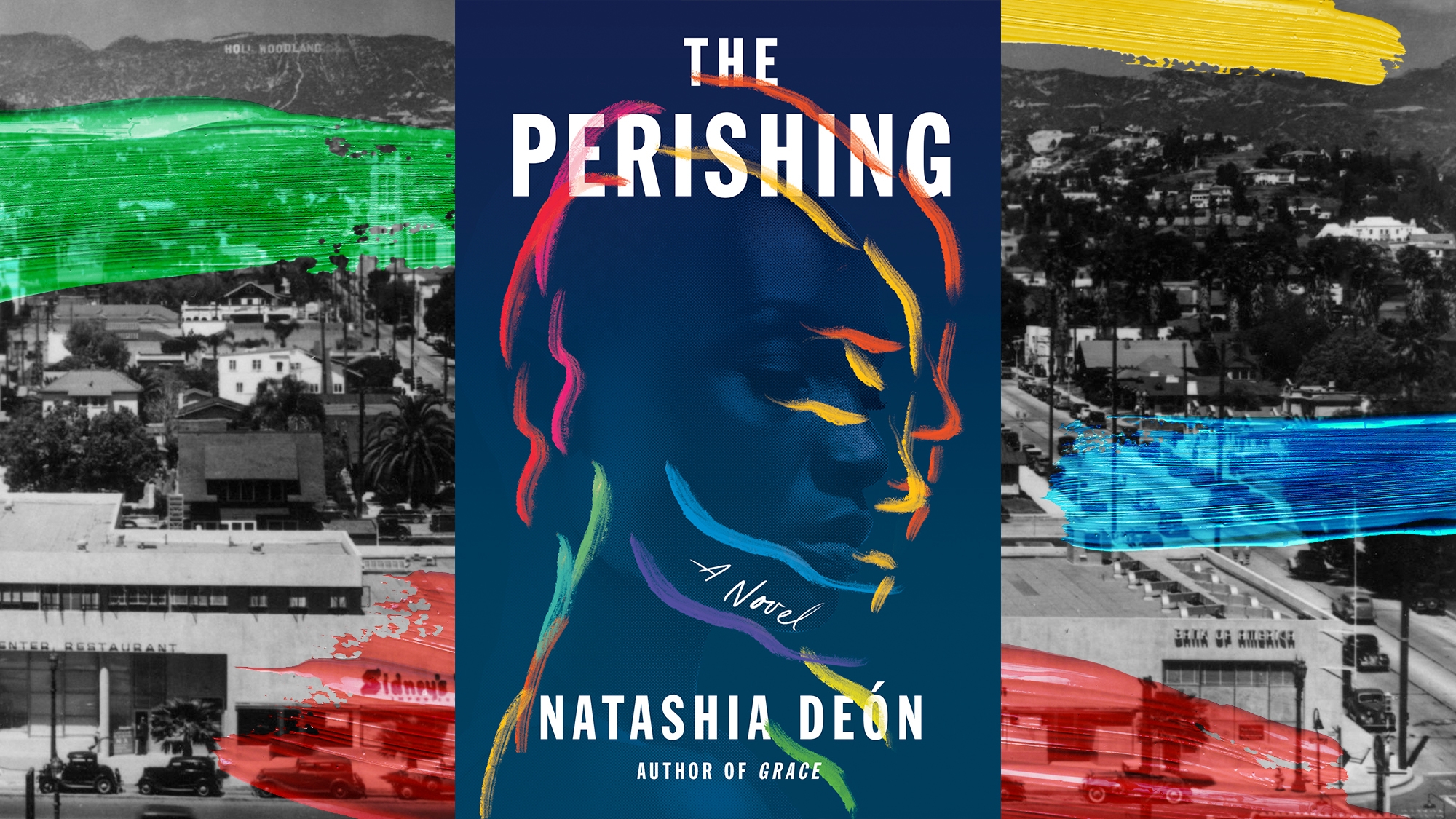

After a debut like that, what’s a writer to do next? Judging by the packaging of her second novel, The Perishing, Deón decided to do something completely different. The description on the back cover positions The Perishing as a supernatural historical thriller in the vein of Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country or P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout. It’s not hard to understand why the publisher is marketing the book this way; it’s the same reason that trailers for M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village promised a creature feature like his previous film, Signs: Some stories don’t fit neatly inside a genre box, but bookselling and moviemaking leave little room for nuance when it comes to advertising.

If you’ve seen The Village, you know it’s more Gothic romance than monster horror. And if you read The Perishing, you’ll see it has more in common with Deón’s debut—or Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing or Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, books in which the speculative conceit plays third fiddle to characters and settings grounded in reality—than the book jacket indicates. If you approach it without genre-specific expectations, The Perishing is a startling, luminous love letter to Los Angeles and one of the best books of 2021.

The Perishing opens with a 30-page prologue that bounces between the year 2102 and the late 19th century, as an immortal narrator remembers snippets of past lives. “Life after life in new bodies, new cities, and new countries where I’ve always been Black, not always a woman,” she says. We meet her as Sarah Shipley, a California woman on trial for murder a century from now; as Charlie, an Arizona boy whose grandfather goes missing in 1887; and as a nameless girl living by the Dead Sea sometime in the distant past. These brief opening chapters are disorienting, as Deón establishes the temporal confusion an immortal mind might experience.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.