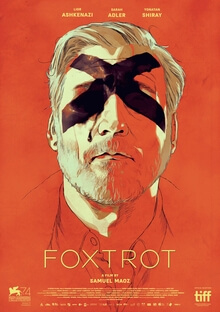

Foxtrot is a striking triptych of war, grief, and fate

The first shot of Foxtrot is through the windshield of a vehicle careening down a desolate country road. It’ll be a while before the full significance of this image is revealed, even to those who suss out the gist of it through context clues. But it’s painfully clear what kind of story Israeli writer-director Samuel Maoz intends to tell by the time he reaches his second shot: a medium close-up of a woman opening a door, processing the appearance of the offscreen strangers standing before her, and promptly fainting. The woman is Daphna Feldmann (Sarah Adler), and it’s momentarily disclosed but instantly obvious that the strangers are men in uniform, at her front door to make her worst nightmare—to make any parent’s worst nightmare—a reality. They don’t have to say a word. She knows why they’re there. She knows her son is dead.

Foxtrot is about what happens next, about the rage and the grief a couple grapples with after this horrible visit. (When Daphna collapses out of frame, her absence reveals a painting that’s just a cluster of black lines, creating a mess of inky darkness at its center—a good visual representation of the abyss that’s swallowed up the Feldmanns.) But the film is also about what happened before, to the dead soldier and to his father, whose own past intersects with the current events in surprising, speculative, perhaps fatalistic ways. Heavy with horror though it may be, Foxtrot turns out to be too conceptually and stylistically audacious to be called a slog; it keeps throwing curveballs, some crueler than others.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.