Oral history Changes is a grounded account of Tupac Shakur’s legendary life

Nearly 25 years after his murder in September 1996, Tupac Shakur elicits complex feelings. Fans across the world praise him as one of the greatest—if not the greatest—voice in hip-hop history. Meanwhile, his musical legacy is often overshadowed by a war of words that may have led to the March 1997 murder of the Notorious B.I.G., a legendary beef that some East Coast rap fans never forgave him for. A 1994 sexual assault conviction sits uneasily with two of the best tributes to women in the rap canon, “Keep Ya Head Up” and “Dear Mama.” His Black Panther family history belies his final year on earth as an aggrieved, money-flouting “baller” who lashed out at enemies real and perceived, a dichotomy fiercely debated in the press at the time. Yet he remains a hero of activists, and his music was widely played at the George Floyd protests last summer.

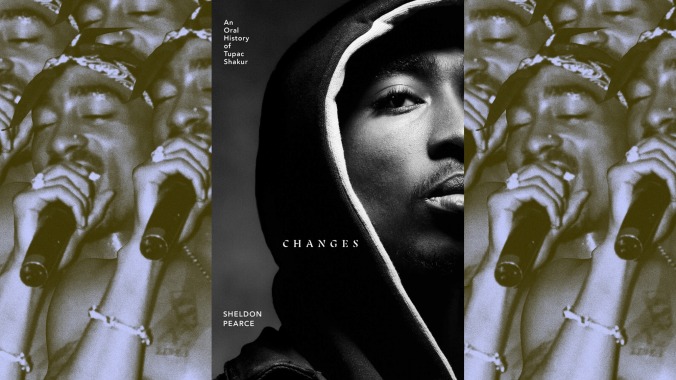

Sheldon Pearce’s Changes: An Oral History joins a bookshelf already teeming with 2Pac arcana, from rhapsodic praise like Michael Eric Dyson’s Holler If You Hear Me: Searching For Tupac Shakur to neoconservative hit jobs like Armond White’s Rebel For The Hell Of It: The Life Of Tupac Shakur. “Pac is among our most well-studied figures,” Pearce, a writer and editor at The New Yorker, acknowledges in a brief author’s note. But instead of speaking with highly publicized figures in his life such as Sean “Puffy” Combs and the late Shock G, he elicits testimony from more than 50 individuals who knew and met Tupac, covered him as a subject in the mid-’90s, or are simply latter-day admirers of his work. The result is a book that quietly tries to humanize an oft-mythologized figure. “This oral history is less about all-inclusive, full-scale documentation and more about texture—about getting to the heart of what Tupac meant to people, how his life came to reflect so different truths,” writes Pearce.

Still, oral histories can have their drawbacks. At best, they create a three-dimensional portrait more dynamic than a standard biography, replicating the countless individual interactions that comprise someone’s public persona. Yet they often drown in noise as a bunch of people with tenuous connections to the subject opine in loud and contradictory ways. Pearce mostly avoids the latter, particularly in wonderful early chapters where Tupac’s former teachers and friends describe his youth in New York, Baltimore, and Marin City, California. In a section that covers Tupac’s return to New York—a pivotal, chaotic era where he befriends the Notorious B.I.G. as well as sundry gangsters while filming the movie Above The Rim, is charged with rape after a nightclub incident, and is shot by assailants at Quad Studios—Pearce maintains calm by bringing in figures like longtime journalist Rob Marriott and scholar Mark Anthony Neal. But the book’s climax, which covers 2Pac’s shooting and subsequent death in Las Vegas, can’t help but descend into LAbyrinth-style speculation and conspiracy theories.

Changes may fail to fully explain the motivations for this most enigmatic of superstars, no matter how many times the book’s chorus points out that Tupac was a Gemini. But at least it makes him seem more flesh-and-blood than the countless statues and murals that pay tribute to his brief yet incredibly eventful life. These four key moments stand out amid all the chatter.

“Most people didn’t know he was an actor first”

Changes has several great anecdotes from Tupac’s fellow actors, students, and teachers. Levy Lee Simon, who performed alongside a 12-year-old Tupac in a production of A Raisin In The Sun at New York’s Apollo Theater, reminds us, “Before he ever entered into the hip-hop world, he was an actor.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.