Lazy Susans, label makers, Brussels sprouts, knife blocks, Sodastream bottles, clogged kitchen drains—Actress is cluttered with the little things of middle-class, suburban, American domestic life. Alternately candid and cagey, Robert Greene’s documentary turns the chores and frustrations of a modern-day homemaker into a study in roles—social and personal, conscious and unintentional, on-camera and off. It isn’t, by any means, a difficult movie, but neither does it take any easy routes.

Over the last few years, Greene has developed a reputation as one of the most cogent thinkers of the ongoing non-fiction filmmaking boom, as much a documentary advocate as a documentarian. He makes films about performance, and the things people reveal about themselves when they hide. (The title of his second feature, the superb regional wrestling doc Fake It So Real, sums up his major theme.) He’s also smart about the form and its history; one of the most striking things about Actress is the way in which it internalizes and blends different techniques, from the archetypal vérité follow-around camera to the sit-down interview, into a multifaceted approach that never comes across as dry or academic, but instead seems to change shape along with its subject.

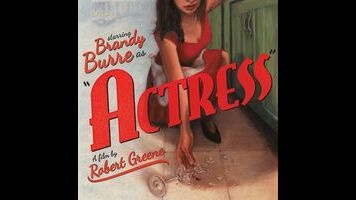

That subject is Brandy Burre, a former stage and TV actor—best known for her role as political fixer Theresa D’Agostino on The Wire—who quit showbiz to raise two kids with her restaurant-owner boyfriend in Beacon, a small town about an hour away from New York City. An early sequence finds Burre seated in the middle of her kids’ playroom, speaking directly to Greene’s camera. “I moved to Beacon, I’m not acting, so this is my creative outlet,” she says. Then she takes a breath, shifts her weight, and starts again, in a different tone of voice: “I moved to Beacon, I’m not acting, so this is my creative outlet.”

From the movie’s first shot—which shows Burre doing dishes in a red dress and pearls, a perfect image of ’50s Formica housewifedom—Actress establishes its subject as a performer, playing wife (though she isn’t married) and mother at home. And when, partway through the film, she decides to get back into acting, she begins to play an actor, reading breakdowns (“Mid-to-late 30s—is that me?” she asks her 3-year-old daughter), getting new head shots, and going to auditions. When her friends visit for Christmas, she plays the still-cool grown-up, getting stoned in the basement, away from the kids.

With its claustrophobic mise-en-scene—all of those carefully organized shelves and seasonal decorations pushing into frame—and its sensitivity to anxieties about age and domesticity, Actress eventually comes to resemble a kind of grainy, handheld Douglas Sirk drama. It becomes clear that Burre feels suffocated—but her only way out is to take on new roles. The title focuses the viewer’s attention on Burre as a performer; not coincidentally, it’s also gender-specific, because the roles Burre plays—and the ones she auditions for—have a lot to do with social expectations of womanhood, motherhood, and desirability. (“There are a lot of wives and girlfriends,” she says, scrolling through casting breakdowns on her iPad.)

Throughout, Greene plays around with information, withholding details about Burre’s personal life and letting scenes play out before giving their context. For his final and gutsiest rug-pull, he presents a charged, slow-motion image of Burre and gives the viewer time to draw a conclusion; then comes the truth, and with it, the sinking feeling that the viewer has projected a role on to Burre that has everything to do with the fact that she’s a woman, and nothing to do with what they already know about her and her life.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)