Ben Dolnick delivers compulsive readability, if not scares, in The Ghost Notebooks

It seems like a lark at first, as these things always do, when Nick Beron quits his job to follow his fiancée (whom he impulsively proposed to), Hannah Rampe, for her new role overseeing a remote museum. It’s a house dedicated to a philosopher who was obsessed with contacting his dead son, and which was the site of a murder some years before. Soon, there are bumps in the night, a diary reveals events that are years in the future, and Hannah—who once suffered a possession-like mental breakdown—grows distant as she immerses herself in the home’s macabre history. “The line between romantic getaway and lonely creepy farmhouse is, it turns out, fairly thin,” muses Nick, who will soon be pacing the house “like a lunatic in a Poe story.”

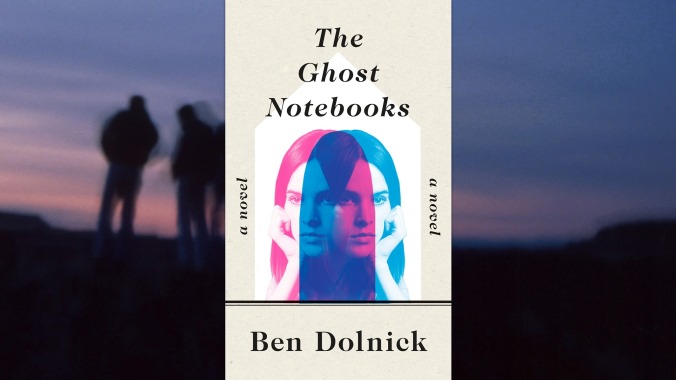

This is the premise for The Ghost Notebooks, the latest novel by Ben Dolnick, which uses the trappings of horror to explore and compound his pet themes of lost and confused young people. (Those who read it to be scared will be disappointed.) If life offers an unending number of ways to not be settled—especially for young creative types who are haunted by every missed opportunity and path not taken—then the infinite time and space of an afterlife can only magnify one’s unmooring. And in-between those forms of consciousness is death: immutable, omnipotent. It can’t be argued or reasoned with. Death isn’t interested in your shit.

Over a series of short, quietly powerful novels, Dolnick has emerged as an author of compulsive readability and real insights. He’s the kind of writer who can easily be overlooked, if not dismissed as a stereotype, as his characters are straight white guys, mostly adolescents or young men in some borough of New York, and the stories generally revolve around first loves, first heartbreaks, or the first time someone they know dies. These familiar elements feel fresh and immediate in his hands, though, demonstrating how it’s the storytelling and not the story that makes a book worthwhile.

He has a gift for metaphor, a way of expressing complex emotions and relationships with a pithy comparison that’s easy to understand but genuinely illuminating, and at the same time isn’t a cliché and never feels cutesy. Here, he describes the shell shock Hannah’s parents have from parenting someone who once suffered a nervous breakdown. “To have watched your child collapse is to live the rest of your life on a partially frozen pond,” he writes. This image is enough to carry their motivations through the entire book, especially their desperation as the ice begins to thaw.