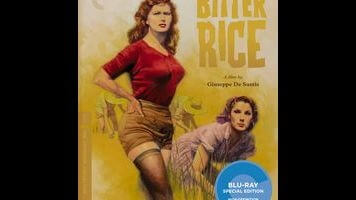

Even in the sociopolitically minded world of Italian neorealism, star quality mattered. That’s why Giuseppe De Santis’ sweaty, grubby 1949 drama Bitter Rice introduces its statuesque star, 18-year-old actress Silvana Mangano, with a flourish worthy of a Marilyn Monroe or a Sophia Loren. In one of the film’s many exquisite long tracking shots, De Santis and cinematographer Otello Martelli move the camera slowly along the side of a passenger train’s sleeping car, catching passengers waking up, getting ready for the day, and looking out their window at a rising commotion. Then the camera continues out into a dusty patch of train yard, where a group of migrant workers have gathered around Mangano’s character (also named Silvana) as she dances the boogie-woogie. Bitter Rice is a story about crime, class conflict, and backbreaking labor. But it’s also about the wonder that is Mangano, as her Silvana chews gum, breathes heavy, and teases men. Even when she’s out in the rice paddies with the other mondinas, she’s a vision, with her torn hose and bare feet.

Silvana’s intro is actually the second extended take in Bitter Rice. The first opens the film: It’s a shot that starts with a radio announcer looking directly into the camera to explain the history and culture of rice pickers, before the camera does a slow 360-degree pan around the train station to show workers singing, families separating, and a pair of cops hunting for the man and woman who just stole a valuable jeweled necklace. Vittorio Gassman and Doris Dowling play the couple—Walter and Francesca—who in those opening minutes separate to elude capture, with the latter hiding among the women shipping out to the paddies. Francesca gets help from Silvana, who figures out the fugitive’s secret immediately, and at times uses it against her.

The first 10 minutes of Bitter Rice more or less establishes what the movie’s going to be: sexy and noir-inflected, with more docu-realistic footage of rice cultivating than the average pulpy crime picture. In an interview included on Criterion’s new Bitter Rice Blu-ray, screenwriter Carlo Lizzani says that “no neorealist film belongs to any one genre,” and this film is a clear case in point. It has the grim fatalism of other neorealist-noir hybrids like Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione (which De Santis co-wrote), but at times it also recalls female-focused Hollywood melodramas in the way it explores the complicated relationships among women. Francesca and Silvana live, work, laugh, and cry together, but they also find themselves on opposite sides of a labor dispute (which, in one memorable scene, they argue by singing their complaints back and forth to each other in the field), and they compete for the attention of a soldier named Marco (Raf Vallone) and for the returning Walter.

De Santis and his producer Dino De Laurentiis had a dual purpose in making a film noir with two femmes fatale. Their intention was partly noble: to record the lives of these hard-working women, who form a sisterhood and a society even while being exploited by bosses and unions. But it’s pointless to deny that Bitter Rice is also meant to be heart-stoppingly sexy. De Santis loads up on scenes of the workers lounging around their barracks in low-cut negligees, and he includes lots of footage of women bending over to plant rice. Mangano’s physical splendor is front-and-center throughout the film, whether she’s hiking up her skirt while dancing or nuzzling up against one of her hunky men, whose hands always seem to brush against her chest on their way up to her face and hair. This was the actress’ first major role, and it justifiably made her a star. (It also landed her a husband. De Laurentiis was married to Mangano from 1949 to 1988. One of their grandchildren is Food Network star Giada De Laurentiis.)

The sex appeal of Bitter Rice probably had a lot to do with the movie getting enough attention in America to land an Oscar nomination for what was then called “Best Story.” (Today it would be “Best Original Screenplay.”) In truth, Bitter Rice’s story is its weakest element. It’s a little one-dimensional, dealing with the fairly predicable machinations among Francesca, Silvana, Marco, and Walter as the latter plans a rice heist.

But the affect of the potboiler plot and all the exposed flesh is that Bitter Rice holds the audience’s attention even as De Santis is passing along valuable information about labor contracts and agriculture. Criterion’s disc adds an hour-long documentary about the director, who’s an often overlooked figure from the era of Visconti, Roberto Rossellini, and Vittorio De Sica. In it, his collaborators point out how skillfully the director wove social issues into what were essentially mainstream entertainments. And yet, watching Bitter Rice, at times it feels like the situation was exactly the opposite. De Santis used a real social issue as an opportunity to glide his camera along strikingly lit piles of grain, and to photograph some of the most beautiful faces and bodies he could find.