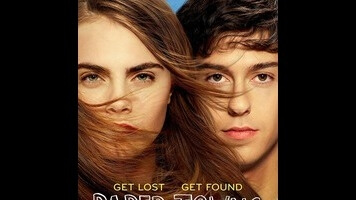

Despite its glimmers of self-awareness, Paper Towns works neither as a teen romance nor as a subversion of the same. Delevingne possesses an almost preternaturally interesting face, but is at best a beginner actor. Thick furrowed brow and cocked head notwithstanding, she’s too feathery a presence to make her an object of sustained mystery, and the script—by Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber, who also adapted The Fault In Our Stars—does her no favors by altering the ending of Green’s novel so that instead of climactically breaking, the central mystery fizzles away like an uncapped bottle of soda, dissipating into a flat, texture-less aftertaste.

But while director Jake Shreier (Robot & Frank) doesn’t do a whole lot with the camera besides make sure that there are people in the frame, he does manage to provoke strong performances from Wolff—who looks kind of like a young Dustin Hoffman, but stretched out like a piece of taffy—and the young supporting cast. The stated aim of Green’s novel was to tweak a certain archetype—what The A.V. Club contributor Nathan Rabin once termed the Manic Pixie Dream Girl—common to romances told from the perspective of young men. In that respect, the adaptation of Paper Towns is a failure. But even as it fails to either develop or subvert its characterization of Margo, it succeeds in complicating all of its ancillary characters.

Like Quentin, they are introduced as broadly drawn archetypes: Bloody Ben, the shrimpy wannabe Lothario who tells tall tales of sexual adventure; high-strung Radar, defined largely in terms of blackness, including a slightly demented montage of his family’s collection of black Santa memorabilia; Margo’s best friend, Lacey (Halston Sage), long settled into a role as the bland, blond sidekick. As the mystery turns into a road trip, the characterizations and performances become more complex and naturalistic; characters who had at first only been sounding boards for Quentin suddenly start talking at length about their own lives. They get their own long, talky scenes without him; they become independent of the plot.

There’s a more palpable sense of physical closeness in Quentin, Radar, and Ben’s impromptu performance of the Pokémon theme song than in the dance—set to a smooth jazz cover of “Lady In Red”—that Margo and Quentin share after sneaking into an office building. Which might just be the whole point—in other words, that the people Quentin knows well are more interesting than the supposedly tantalizing mystery that is Margo. However, it leaves an empty space at the center of the movie.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.