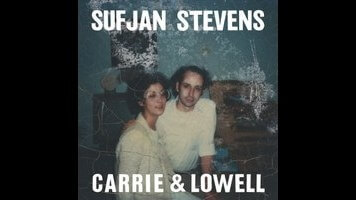

The title refers to Stevens’ mother and stepfather, though the lyrics address the former more directly. She left Stevens and his siblings when he was a baby, and his memories of her stem mostly from summer visits to Oregon when he was a toddler and grade-schooler. He was with her when she died a few years ago, and his attempts to reconcile his feelings—of abandonment, love, resentment, confusion, self-loathing, nostalgia—are the sensitive tendons that resist and then go slack throughout these songs. Most feel like attempts to heal by way of quiet confrontation—call it primal whisper therapy. It’s tricky territory to navigate in these cynical times, and hardened hearts and ears might find it off-putting. But meet Carrie & Lowell on its terms and it’s revelatory.

In an unsurprisingly candid interview with Pitchfork recently, Stevens described the process of wrangling the emotions surrounding his mother’s death simply: “It wasn’t very fun.” While that’s true of the record, too—Carrie & Lowell will be uneasy listening to anyone paying close attention to the lyrics—it’s crucial to Stevens’ art. The best songs of his career alchemize sorrow and joy in ways that seem positively otherworldly, and that combination is in full force here: Even “Fourth Of July,” which ends with the repeated refrain “We’re all gonna die,” is able to capture something bright in the darkness—the act of letting go.

On “All Of Me Wants All Of You,” Stevens allows himself to wallow a bit, accessing anger but leavening it with sweet vocal melodies; on “Drawn To The Blood,” he channels Elliott Smith with a simple acoustic guitar line and a fist shaken toward the heavens. He also reflects on suicidal thoughts on the delicate “The Only Thing,” wondering aloud whether he even wants to survive what he’s going through.

But for every moment it concedes to the once-deadly sin of despair, Carrie & Lowell lifts: Even as it doubts itself, “Eugene” finds comfort in the painful past—a teacher who couldn’t pronounce Stevens’ first name, the sleeve where his mother kept her cigarettes. And then there’s that song with the big breath, “John My Beloved,” which longs for reconciliation before it’s too late. Over a metronome-like loop, some tape noise, and a distant piano, Stevens reaches out: “So can we be friends, sweetly, before the mystery ends?” He’s looking, as he so often has—as most people are—for a genuine connection, a chance to be nakedly honest in both his joy and sadness.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.