Women traveling alone are supposed to follow certain rules. Never go anywhere without someone knowing where you are and when you’ll be back. Don’t accept drinks from strange men. Don’t get into a stranger’s car. And no matter what you do, never go home with someone you just met, especially in a new city where you don’t know where you’re going. These rules aren’t always strictly obeyed, of course, particularly when a seemingly gentle man with piercing blue eyes and a charmingly incomplete understanding of the English language is involved. But the little voice in the back of your head is always there, reminding you that every time you sneak back into your hostel still wearing last night’s clothes, you’re lucky to be alive.

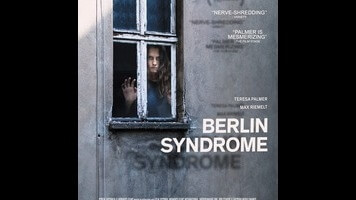

It starts out innocently enough: Clare meets Andi (Sense8’s Max Riemelt) on the street while backpacking through Europe. They chat; they flirt; they go out on the town; they eventually tumble into bed together. Even the events of the morning after—when Andi “forgets” to leave keys behind for Clare after locking her into his apartment in a lonely stretch of abandoned buildings—seem relatively innocuous, or at least forgivable enough for some shower sex and clubbing after he returns. It’s not until the day after that, when she discovers that his windows are reinforced and his apartment is free of sharp objects, that Clare realizes Andi has no intention of letting her leave.

The exact duration of Clare’s captivity is unclear, although the changing weather indicates that months must be going by. There’s also not a whole lot to do while she’s stuck in his apartment day after day, save rummage through the cupboards in search of weapons and prepare to fight him when he returns. Whether Shortland intends to put us into Clare’s numbed state of mind with these long, repetitive periods of quiet punctuated with increasingly frustrated attempts to escape is unclear. Palmer admirably commits to the part, and is unafraid to get dirt under her fingernails and grease in her hair as her situation grows more desperate. But we end the film knowing little more about Clare’s life outside of this one traumatic episode than we did at the beginning, which seems like a real missed opportunity.

The most frustrating ambiguity, however, is Berlin Syndrome’s focus on Andi. A good portion of the film is devoted to showing his everyday life as a high-school English teacher, scenes that carry a certain weight given the knowledge that Clare is imprisoned inside. But these, too, contain no great insights. He inappropriately leers at a student, but rejects her advances. He has an estranged relationship with his mother, and makes sexist comments to a co-worker’s wife at a party. But neither are abnormal enough to even begin to explain the extreme nature of his behavior at home. Similarly, the interactions between Clare and Andi are downplayed in such a manner that it’s hard to tell whether she’s experiencing Stockholm syndrome, or just humoring her captor. It threatens to go beyond the banality of evil, and just become banal.

The script, based on a novel by Melanie Joosten, is tight in the sense of tying up all its loose ends, and Shortland’s mise-en-scène, full of close-ups of bruised limbs and peeling paint, effectively enhances the grim realism of the scenario. But in translating Joosten’s book for the screen, the most fascinating element of the story—the psychology of both victim and predator—is underplayed. That’s not to say that every film of this type has to have the pummeling intensity of Hounds Of Love, another recent kidnapping drama. But by focusing exclusively on the murkier, more drawn-out aspects of Clare’s captivity, Berlin Syndrome runs the risk of muting its impact as well.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)