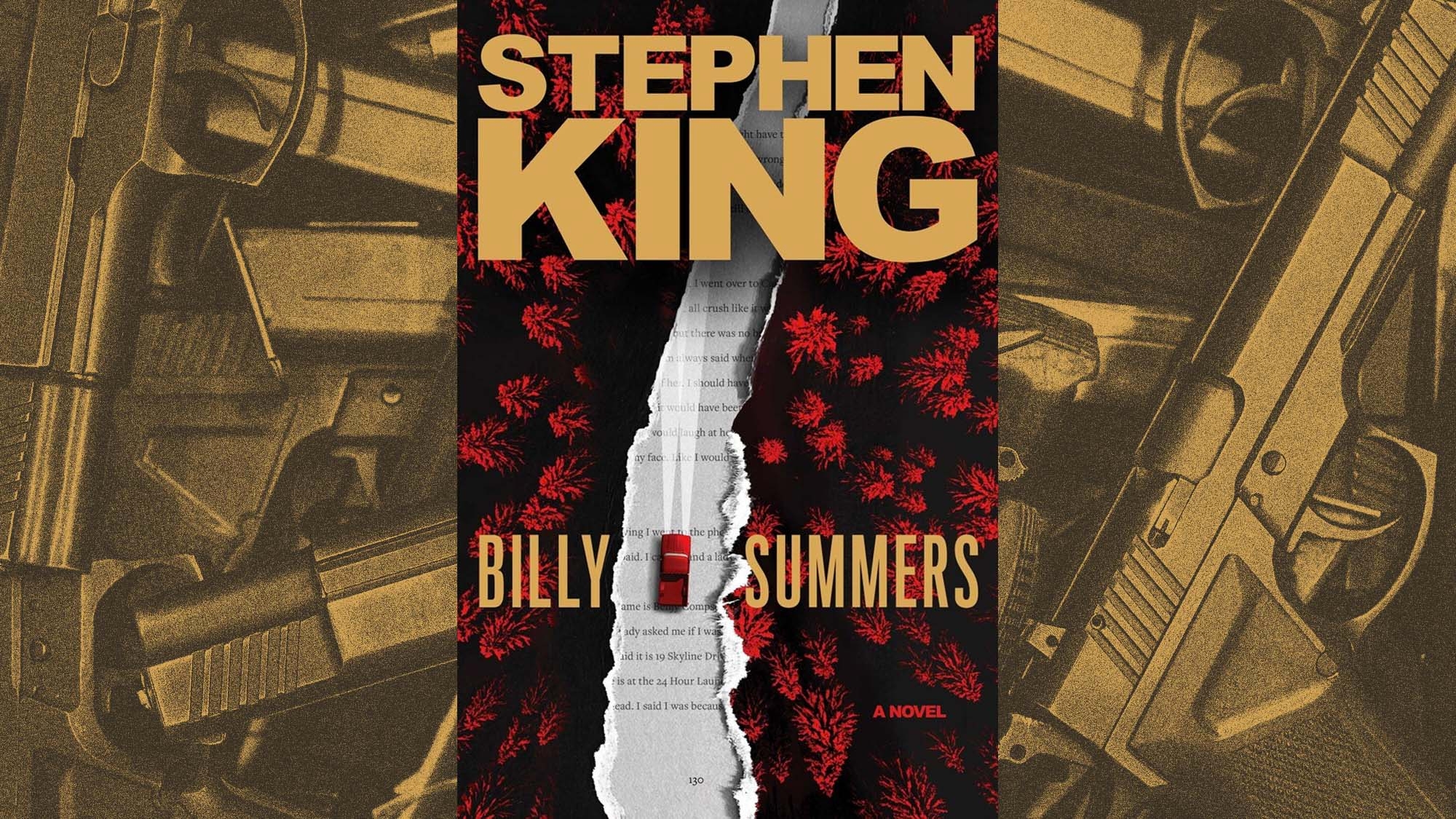

Stephen King evokes John Wick and pandemic anxiety in the tense, fractured Billy Summers

The first half of King’s new crime novel is some of his best work in years. The second half is a different story.

The final page of Billy Summers—Stephen King’s latest effort to master pulp crime fiction just as he tamed horror several decades ago—includes, like many of King’s books, a note saying when he wrote it. In most of King’s novels, this addendum serves as little more than a cheery footnote, a reminder of the hard work and the sheer amount of time that must be poured into the author’s brick-heavy tomes to bring them to life. But in Billy Summers, those dates arrive with a meaning that no one could have anticipated when King first sat down to craft his story of a hitman with a heart of gold: June 12, 2019 – July 3, 2020.

To be clear, Billy Summers is not a pandemic novel, at least not in the traditional sense. Outside of a few allusions to the COVID-19 lockdowns, King resists the urge to import details directly from a reality that has sometimes felt cribbed from the pages of his most famous works. But the steadily growing cabin fever is nevertheless inescapable as one dives deeper into the book, and a first act of stunning formal control gives way to a second half that is frequently unfocused, lurid, and, at times, clichéd. All of which builds to a climax that seems to pull from the darkest recesses of home-brewed Twitter and cable news paranoia; it’s wish fulfillment for those living in a world where the rich and powerful orchestrate acts of monstrous evil, while we’re all stuck at home, brokenly clicking along. The action then settles, almost miraculously, into an epilogue that brings the book’s best qualities back to the forefront.

But first: That opening half, which sees its title contract killer shacking up in a nondescript Midwestern city, waiting several months for his next target to be delivered to a nearby courthouse. In the meantime, the Iraq vet-turned-freelance-sniper must blend in with the locals, a setup King uses to get the wheels spinning on a delicious engine of tension. By the time the date of the hit arrives, our uber-competent undercover anti-hero is running something like five different identities in an effort to keep everyone—his neighbors, his employees, himself—in the dark about what’s actually going on. The most prominent of these is also the one that tips the book into more recognizable King territory, as Billy’s employers (having bought into his persona as a slow-witted murder-savant) mockingly set him up as a first-time novelist to explain his extended stay in town.

If Billy Summers has a thesis—beyond the burbling morass of vengeance fantasies that threaten to transform the second half into something akin to Stephen King’s Death Wish—it’s in the sequences that dive into Billy’s attempts to turn his cover gig into a real one and filter his life story into prose. King has written so many author-protagonists over the years that it’s tipped over from a running joke into simply being part of the background radiation of his oeuvre. But he’s rarely put this much time and energy into depicting the actual cathartic work of the job, up to and including drafting whole chapters of Billy’s writing as he processes his abusive childhood and military service to untangle the web of identities he’s crafted around himself. The rapture with which Billy realizes he can finally peek out from behind the masks and speak in his own voice (if only to himself) could have been corny in another book, but in King’s hands, it comes off as infectiously genuine. In addition to those loftier ideas, these excerpts are also a chance for King to engage in a bit of metafictional gamesmanship, crafting text that reads like the work of a gifted beginner, distinct from the more familiar tone used in the rest of the book.