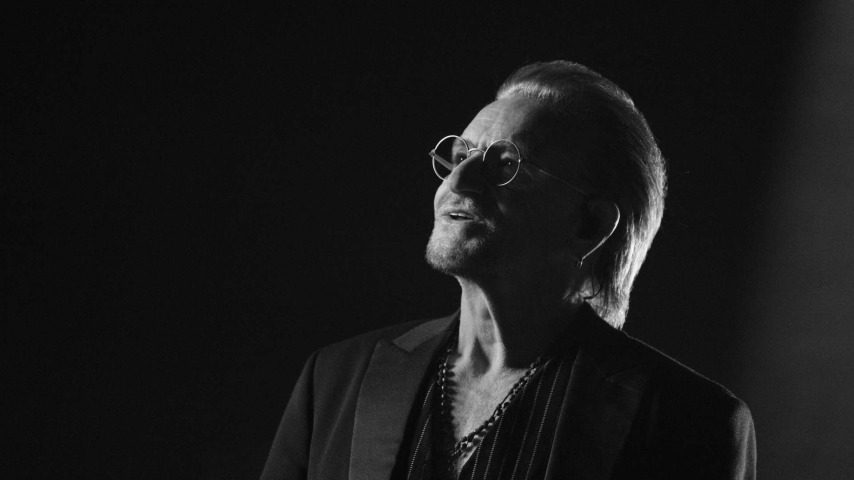

Bono's unvarnished earnestness makes his Stories Of Surrender worth hearing

The U2 frontman continues opening up in the engaging, moving filmed stage memoir.

Photo: Apple

In November 2022, Bono, the frontman of globe-straddling Irish rock band U2, set out on a 14-date book tour for Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, a memoir he cooked up during the pandemic shutdown. While based around read (and often acted out) passages as well as stripped-down musical performances, these shows also included extemporaneous monologues and other shards of recollection. Bono: Stories Of Surrender is (if one can keep up) a discrete, unique, black-and-white film adaptation of the stage adaptation of “me book what I wrote meself,” as Bono says.

While chiefly serving as an engaging conversation piece for those already familiar with the man and his band, director Andrew Dominik’s film is also an artistic, effectively streamlined celebration of reflection. Through its subject’s intensely personal reminiscences, a moving treatise emerges on the inherent value of identifying, exercising, and in some cases exorcising the angels and demons that most animate us.

Bono is a curiously polarizing figure across swaths of the Internet, for reasons that are sometimes difficult to pin down. Part of it can be traced to the automatic-download iTunes release of 2014’s Songs Of Innocence, which really bothered a lot of Millennials who now readily accept all manner of technological intrusion into their lives. A bit of it is from the “shut-up-and-sing” crowd who’ve grown tired of his activism, though that’s an odd stance for any fan who was ever serious about U2, since they’ve supported their beliefs for decades.

If you ask around, though, it’s Bono’s general “too-muchness” that seems triggering for most detractors. That sentiment is most rooted in his impulse to overshare, to deconstruct the image of the messianic rock star. Some U2 songs, like “Sunday Bloody Sunday” or “Pride (In The Name Of Love),” tell obvious stories. But Bono has always been driven to both explain the narrative inspirations of almost every song and, in U2’s lyrics, to engage in no small amount of self-devaluation.

For people who instinctively crave a bit more mystery and swagger in their rock ‘n’ roll, that makes him uncool. The counterargument to this is that, by putting the roiling inner contradictions he feels on front street, Bono is actually more authentic and refreshing. It’s that unvarnished earnestness that is at the core of Stories Of Surrender‘s appeal. This is a work, in both its chosen stories and its form, which tries to reach out and bridge divides—divides between family and friends, divides in the world, and divides one can feel within themselves.

The film opens with Bono bringing a dark poeticism to his recounting of a health scare (a blister on his aorta during Christmas 2016). The rest of the stories will be largely familiar to U2 fans. There’s the exaltation of his wife Ali and his bandmates (the latter represented by three empty chairs), all of whom he met in the span of one week as a teenager. The youngest son of a Catholic father and Protestant mother, the defining event of Bono’s adolescence was when, at 14, his mother Iris collapsed and died at her father’s funeral, leaving Bono adrift in a home where grief was unspoken about.

There are amusing digressions too. Considerable time is given to the story of how Luciano Pavarotti (much to the consternation of Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen Jr.) crashed a band rehearsal to pitch a concert performance debuting “Miss Sarajevo” in Modena, Italy. Bono injects levity into the crisis of faith that three members of U2’s early-career dalliance with the devout Christian sect Shalom brought about, noting manager Paul McGuinness’ shrewd parrying of their consideration of dissolving the group: “Would God think it okay to break a legal contract?”

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.