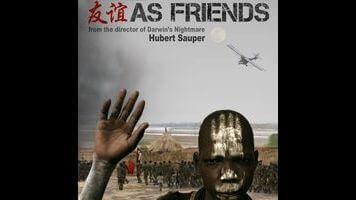

Sauper is best known for the 2004 film Darwin’s Nightmare, which depicts the gross social inequities surrounding the Tanzanian fish-processing industry as though it were the prologue to a zombie epic or eco-thriller: the tipping-point moment right before the starving, diseased hordes rise up against the meddling elites who ruined their lives. We Come As Friends is less alarmist, though it hammers just as hard at outsiders who couch their own self-interest in humanitarian terms. The documentary was shot over the course of several years in Sudan, right as Africa’s biggest country was splitting into a majority Muslim, China-allied north and a nominally Christian, America-friendly south. Traveling around in a small airplane that he made himself, Sauper ignored political and military boundaries as best as possible, so that he could catch the occupiers and the occupied where they really live.

As with Darwin’s Nightmare, We Come As Friends sometimes values startling images over empathy. Sauper trains his camera on Sudanese villagers who look damaged and/or frightening, and while he has revealing conversations with many, he also makes sure to include a few scenes where the natives greet him with suspicion and veiled threats. One group demands to know why anyone on a friendly mission would need to stay in their community overnight. Later, a smiling soldier says, “I am Christian, and I need to know you are also,” suggesting that the wrong answer would mean the end of that plastered grin. Sauper isn’t immune to the Western habit of framing Africans as dangerously exotic. (Then again, Westerners don’t have a monopoly on cultural ignorance, as evidenced by the scene where a Chinese oilman tries to remember which U.S. president gave the “I Have A Dream” speech.)

The big difference is that We Come As Friends is observational, while the institutions Sauper is watching here are actively tampering with Sudanese customs, in the name of improving their economy and living conditions. The movie’s most jaw-dropping sequences involve a group of Texan evangelical Christians who force screaming children into clothes and shoes, while quoting from the Bible and half-jokingly referring to the newly formed South Sudan as “New Texas.” But there’s just as much reason to be concerned about the aid worker who shows off his proposed model for a more orderly village and then mentions that his young daughter wants to add an ice cream parlor and a safari camp. There’s no malice intended by these interlopers; but still, behind every “we’re here to help” is an implied “so we can take what we want and then get the hell out.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.