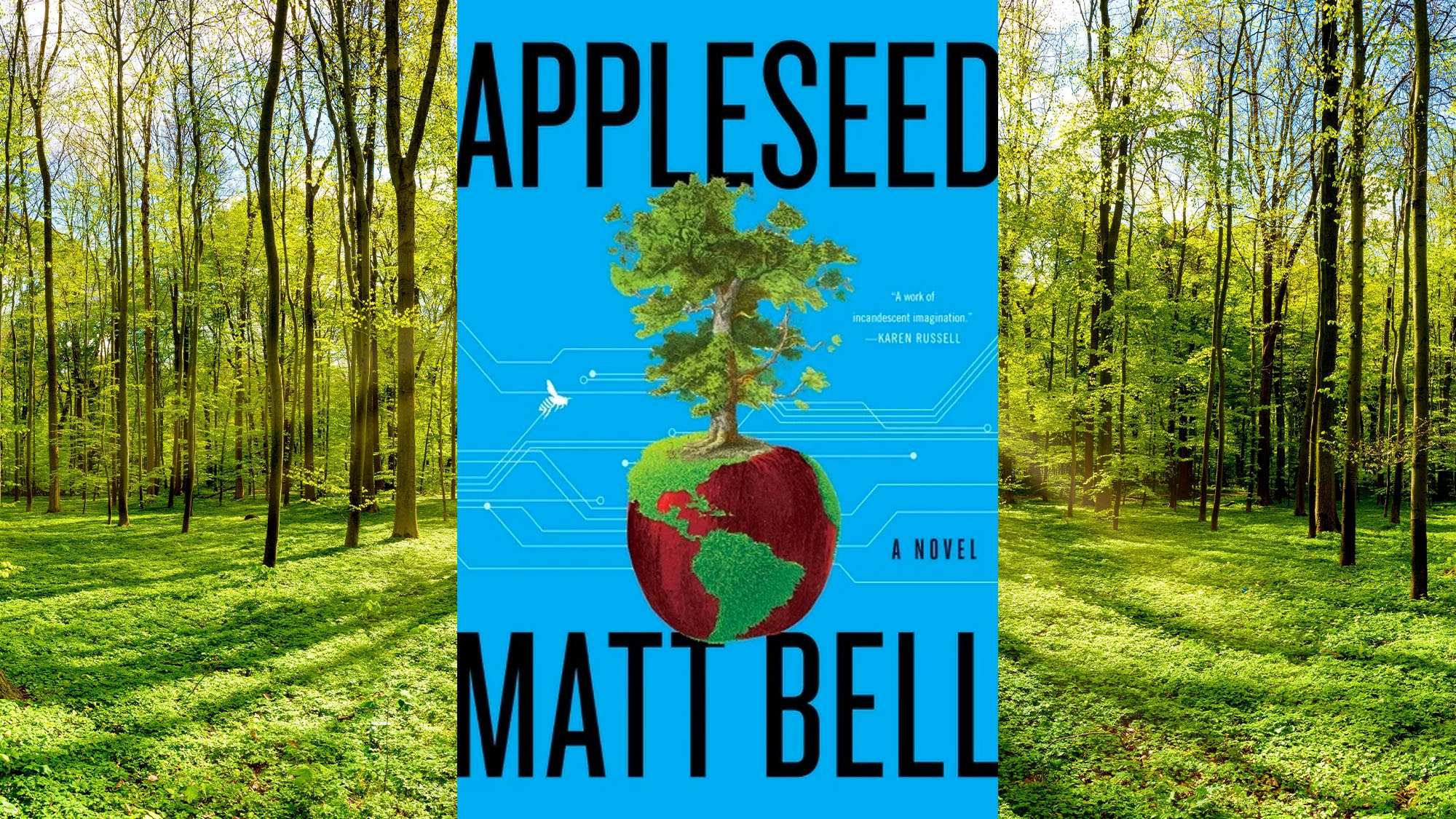

Cover image: Custom House Graphic: Natalie Peeples

At its best, dystopian fiction shines a light on a real-world problem like sexism, wealth inequality, or authoritarianism and pushes it to an extreme. The exaggerated story helps provide perspective and asks readers to grapple with the issues raised. Joining a crowded field of speculative fiction writers penning bleak tales about the perils of climate change is Matt Bell. Offering little more than misery and despair, his latest novel, Appleseed, concludes that humans are incapable of change, headed toward the extinction we deserve.

“[T]his wasn’t the world anyone wanted. A sullen midwestern dystopia…” Bell writes of America’s blighted breadbasket where about a third of his book takes place. The observation also describes this dense, depressing novel. While Bell occasionally embraces the pacing of a techno-thriller, most of the more than 450 pages are devoted to sullen characters brooding about how the world has been diminished and moving slowly toward a single significant choice they think might improve it. There’s something to be said for grappling with agency in the face of momentous forces, but Bell doesn’t provide enough depth to the characters or a sense that their actions matter, making it difficult to follow them on their long journey.

Bell, whose previous works include the dystopian novel Scrapper and the fantastical In The House Upon The Dirt Between The Lake And The Woods, doesn’t lack ambition. Appleseed adopts a structure similar to N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season, with the story split across three timelines, though the connection between the characters that each follows is clear far earlier here. The genre-bending novel mixes bio-punk tropes with the story of Johnny Appleseed and the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Yet there’s no explanation for why the fantasy aspects exist or how they work, and it feels like a way to avoid going too deep into science fiction. One character is able to revolutionize cloning and 3D printing because she finds Orpheus’ head, for instance; what it and the Furies were doing for the past few millennia is never relayed.

One of the protagonists is Chapman, a faun traveling through 18th-century Ohio with his human half-brother, Nathaniel, as they plant apple trees to help make the land more appealing to new settlers. He appears to be the only one of his kind, yet this is not explained either. Chapman thinks that one of the trees might provide him with the antidote to the Garden Of Eden’s Tree Of Knowledge, a Tree Of Forgetting that would let him feel at home in either the world of man or beasts rather than having to walk the boundary between the two. Nathaniel believes the settlers will pay him handsomely for work he can’t prove he did a decade ago. The brothers are both naive and cruel in their constant spats.

In the near future, John is a brilliant engineer turned eco-terrorist. He’s returned to Ohio from a campaign blowing up dams in the Western U.S. to try to tear down Earthtrust, the agricultural megacorp he founded with his ex-girlfriend, Eury. This plotline delves into GMOs, climate migration, and corporate overreach, as John and his allies infiltrate Earthtrust and set up a violent confrontation with Eury. Unfortunately, the spycraft and fast action don’t deliver much in the way of thrills, since the outcome of John’s efforts is already made known in the third storyline, which follows C, an artificial creature trying to survive alone in a frozen far future.

Between his version of the expulsion of the Garden Of Eden and the tale of Aristaeus, the Greek god of agriculture, Bell argues that humanity is guilty of the original sin of attempting to tame nature and refusing to acknowledge that some things should be left untouched. Chapman’s chapters in particular are filled with lush descriptions of thriving forests and how they’re despoiled by settlers who kill animals, clear trees, and eat plants. Entire pages are devoted to listing every animal native to Ohio, all of which Bell imagines will be driven extinct due to humanity’s mix of malice and indifference.

John’s chapters are deeply techno-pessimistic, embodying the philosophy that science will never make things better for anyone except for those in power. He and Eury try to imagine ways to save humanity and the Earth’s plants and animals through bioengineering, but just create tasteless apples and tame wolves. Although Eury offers salvation to desperate climate refugees, she’s always the one in absolute control, unlike John, who is perpetually pushed along by more powerful personalities. Eury is intriguing in that she truly seems to believe her own hype about not only saving the world from starvation but also giving people dignity in her agrarian enclaves.

“No more clearing filthy plates off a table where you’d never be invited to sit,” she promises. “No more crushing your spine in an office chair, hunched in a cubicle, your blank expressionless face reflecting a monitor’s glow.” Eury is nuanced if not sympathetic, though it’s hard to believe the monetary and political power she’s amassed given her naïveté. She immediately welcomes John back into her inner circle, setting herself up for sabotage, and then reveals her world-changing plans on live TV like a supervillain, complete with a countdown timer. She’s surprised when everyone rises up to stop her.

Even those with the best intentions can fall to their own hubris, Bell says, and elites shouldn’t be able to make decisions for everyone else, something that applies equally to Eury’s schemes and the way John and his allies try to subvert them. Bell doesn’t believe that consensus can be reached on how to stop climate change in time to make a difference and that we will be doomed by our inaction. His dismissal of heroism on any scale is both bold and dispiriting.

Bell has a propensity for using repetition to emphasize his points, resulting in some plodding prose, such as a section on homesteaders trapping wolves they blame for lost livestock: “wolves struggling in steel; wolves dead of bloody injuries and poison. Wolves with broken forepaws, shattered skulls; wolves with black tongues, bulged eyeballs.”

Late in the book, Bell acknowledges, through a supporting character, the laziness of having a singular villain in a story about environmental degradation: “The problem is bigger than any one person, any one company or government: the problem belongs to every last person; until it’s solved everyone remains complicit, even if they resist.” Yet Bell does not think the problems he explores can be solved at all, and by his own logic, there is no redemption to be found in resistance.

Author photo: Jessica Bell

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.