The apocalypse is starting to drag.

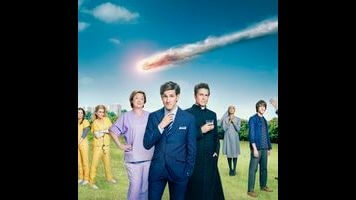

Three episodes into a 10-episode run, “Still Stuff Worth Fighting For” continues to expand the putatively doomed world of You, Me And The Apocalypse, introducing new characters but without the animating detail and thematic unity of the premiere.

Father Jude and Sister Celine meet Jane Doe (Grace Taylor), the giraffe-costumed resurrected 6-year-old presumed by a crowd of unwanted followers to be the Messiah, and her vociferously anti-religious mother—Layla (Karla Crome), Jamie’s missing wife. Jamie and Dave are held captive by Skye (Fiona Button), Ariel’s one-time girlfriend, now enormously pregnant and frighteningly ready to use her nail gun. We get a closer look at both Rhonda’s brother Scotty and husband Rajesh (Prasanna Puwanarajah), who speaks for the first time in the series, and at her son Spike (Fabian McCallum) and his shiftless biological father Tim (Nicholas Pauling). And Rhonda meets Buddy (Nick Offerman), who first holds her at gunpoint, then takes her in and feeds her before changing into a dress because “just once in my life, I would like to be myself.”

It’s a worthy sentiment, the desire to be oneself, but this episode’s new characters don’t seem like… well, much of anyone, really. The first two installments of this limited series are loaded with lived-in detail, but the details of “Still Stuff Worth Fighting For” feel like a random assortment of whimsy for whimsy’s sake: a potential Messiah in a giraffe costume (why? and how did it survive the car accident she herself did not?), a loner living out in the desolate New Mexico countryside with a collection of outdated print dresses (Buddy doesn’t need shoulder pads, folks, look at those shoulders!), a solitary free spirit whose pregnancy and delivery are an excuse for Jamie to peer desperately at a silent newborn and urge him to breathe because “there’s still stuff worth fighting for, there’s still stuff worth fighting for.”

There’s more talk of chaos in this episode, but for the first time, You, Me And The Apocalypse is as inert and out of scale as the rickety model Jamie and Ariel’s mother abandoned in the commune’s attic room. Mary’s small, static vision of Slough during the rapture is all out of whack. The proportions are off—cars of different sizes litter the paint-and-cardboard landscape—and so is the timeline, with the shoebox holding her infant son taking up a huge chunk of the carpark where she left him decades ago.

“Still Stuff Worth Fighting For” breaks the spell of mixed hilarity and gravity that made the first two episodes so entertaining, but there are still moments of excellence and effectiveness here. It’s visually striking, especially when Jamie, Skye, and Dave leave the attic and the camera lingers over Mary’s model of the end of the world: a nude figure atop the roadway sign for Slough, three of the Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse guarding a gated estate, a car waiting outside… then the grainy overhead shot of the car resolves into an actual car, its driver reaching out to open the gate.

Once inside the big house, the two stone-faced underlings from the car submit to frisking, don isolation coveralls, and push through curtains of protective sheeting for a private audience with a barely seen woman. (That’s Diana Rigg behind the plastic and the breathing mask.) At the silent command of the woman behind the curtain, the operatives flip through a dossier with photos of Rhonda, Scotty, Ariel, and Father Jude, asking who they are “and what do you want us to do when we find them?” This attempt to give the “Still Stuff Worth Fighting For” some overarching unity is both redundant—we know everyone’s tied together, in part because each episode opens with them or their cohorts in the bunker together—and feeble, but it does pave the way for more interweaving in the next episode.

The performances in “Still Stuff Worth Waiting For” are strong, even as the storytelling slows; there’s still stuff worth watching for. Rob Lowe’s gentle solemnity as he advises Sister Celine on the urgent, implacable power of repressed desire gives the scene more weight than the dialogue alone could inspire. His declaration that “in the real world, it is always about money or sex” ignores vast, unplumbable depths of zealotry. At this stage, it’s hard to know whether that’s simplistic dialogue or a gesture toward the world-weary priest’s inexperience with “the real world,” but either way, he says it all with a quiet half-smile that only emphasizes his seriousness.

As (I’m sorry) labored as Jamie’s plea to the baby is, Mathew Baynton’s (really, really sorry) delivery highlights what a delicate balancing act he’s performing, switching between flippant, sometimes suddenly frightening Ariel and Jamie, who’s gentler but also more agitated and uncertain. More than that, this speech hits a sweet, slightly frantic note: Even in this world of doom and destruction, where everything Jamie thought he knew has blown up as surely as the world itself will shatter in 32 days, the intensity of his chanting is a kind of benediction, a prayer not just to the baby, but to the universe, that this—this one life, this whole world—should continue, if only for a little bit.

Stray observations

- Would a Polish hospital really use the anglicized Jane Doe?

- It’s Sister Celine’s job, and arguably her new calling, to contribute to their search for (and debunking of) a possible Messiah. It makes little sense that she’d keep quiet about Jane Doe’s impossible knowledge of her dead friend, Sister Sofia, or her mention of the voice telling her about “four horses, a white, a black, a red, and a pale,” that are all part of a greater plan.

- “‘What’s the plan?’ Oh, um, let me think, I’ll take the guards out with my nunchucks while you disable the motion detectors, does that sound good, Batman?”

- Father Jude, after Jane Doe doesn’t laugh at his joke: “No? Well, you’d laugh if you understood monastic architecture.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.