2025 offered a bracing reality check for music lovers who revel in organically stumbling upon a new favorite track: Even the strongest level of discernment can’t fully shield you from AI.

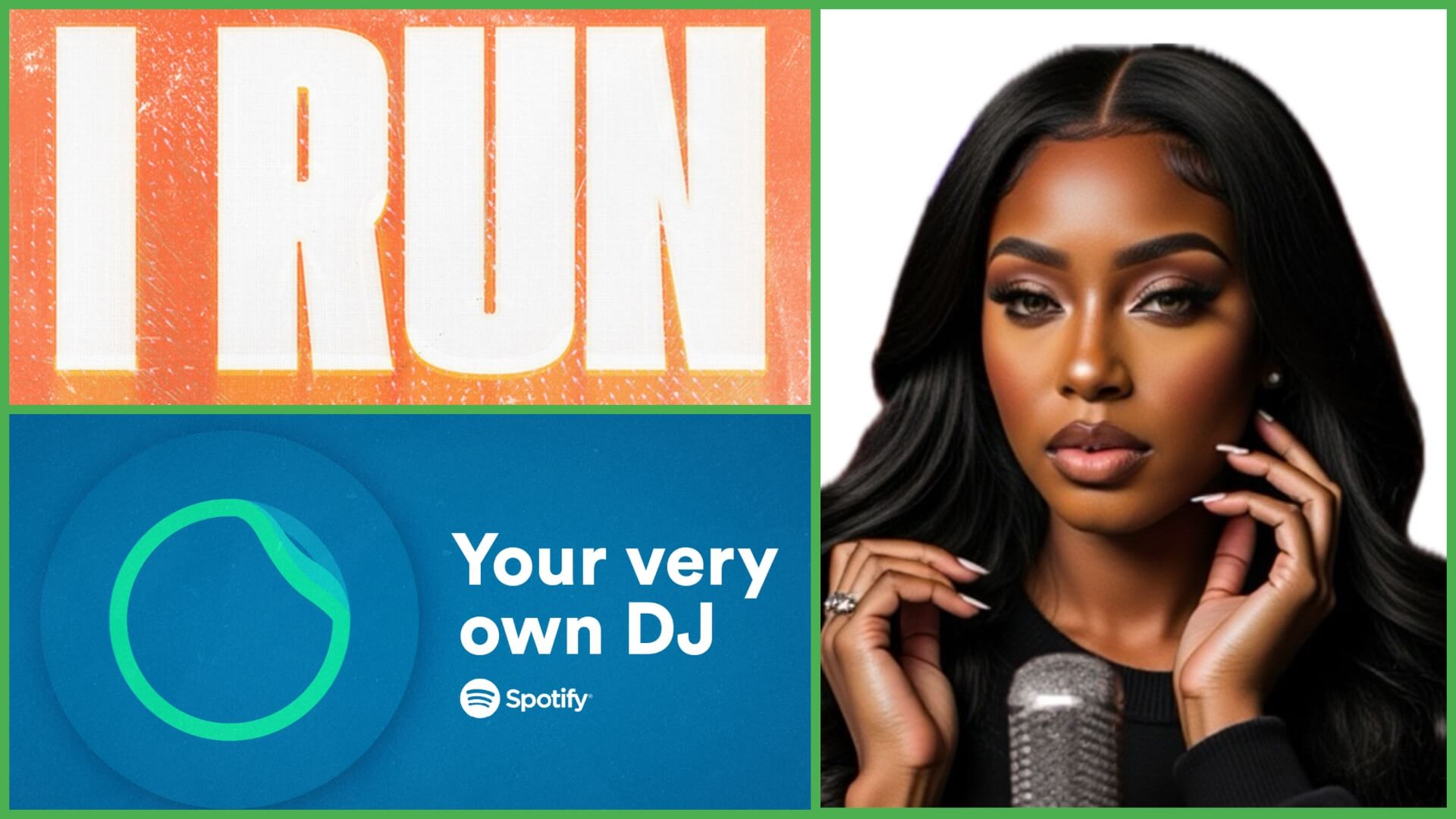

In October, a song called “I Run” materialized on TikTok, an unrepentant earworm of an EDM track that seemingly commandeered everyone’s For You Page. Users fell hard and fast with some even crowning it the “song of the year” in between pleas for its release on streaming platforms. The production, tight and unrelenting, received a lauded boost from siren-like vocals that fans insisted belonged to British R&B songstress Jorja Smith. Before long, the song climbed to #11 on Spotify’s U.S. chart.

But it wasn’t actually her. Smith denied any involvement with the song while acknowledging the uncanny similarities between its vocals and her clockable croon, leading internet sleuths in search for the mystery singer down an unexpected rabbit hole. Soon after, users discovered that the track was actually released by HAVEN., an emerging project from British producers Harrison Walker and Jacob Donaghue. They admitted that the vocals were produced using Suno, a generative AI platform, to “transform” Walker’s voice into something completely unrecognizable. The revelation triggered a now familiar sequence: takedown notices, industry panic, and the song’s exile from major streaming platforms. Billboard withheld it from the Hot 100. Spotify confirmed no royalties were paid. The AI machine had been caught but only after it offered the commerce gods proof of potential profitability, and the uncertainty from that still lingers.

The ordeal is an unwelcome confirmation of a reality we’re trying to shake like a bad dream: AI-produced music is real, it’s imposing, and in 90% of cases, it’s egregious garbage. The remaining 10% is where things get complicated. Because before anyone suspected anything, people loved it, and not in the ironic way the internet sometimes turns generated clips of chaotic Grammy moments and toddlers posing as Bravolebrities into viral hits. They loved it the way you love a song that finds you at exactly the right moment. In turn, listeners helped it reach certain success, right before they felt the rug-pull of deceit. That whiplash, from genuine enjoyment to retroactive rejection, encompasses the real questions at the core of this: What happens when you actually like the AI slop? How can you fight against something when you aren’t even aware that you’re in a fight, especially when the music industry’s largest distributors aren’t really incentivized to fight alongside you?

Music has always had a fraught relationship with technology. In the early ’70s, synthesizers were considered by many rock purists as “musical cheating,” so much so that Queen included a promise of “No Synthesizers!” on the covers of their albums (their stance, however, changed in 1980 with The Game). Drum machines were similarly scrutinized during that time, deemed soulless and strongly lacking an element of excitement that could only come with impassioned human improvisation. The pitch-correcting sorcery of Auto-Tune really triggered hand-wringing once T-Pain popularized the practice with his 2005 debut. Its impact was so lasting and widespread that Usher confronted T-Pain on a plane in 2013 with the claim that he “ruined music,” an interaction that haunted the “I’m Sprung” singer for years.

But those shifts, however daunting, didn’t evoke quite the same urgency. For the most part, those technologies enhanced human performance; they didn’t replace it. Cramming synths and electric drum beats into a track didn’t negate their need for human production and solid voices to carry it. Auto-Tune might be able to smooth out a rough vocal performance but the person attempting to sing into the mic was still, you know, a person. Synths and Auto-Tune weren’t being constantly pushed as an inevitability by nearly every creative industry, from acting to advertising, the way AI is.

This moment feels different. AI-generated artists, in most cases, aren’t augmenting creativity; they’re simulating it wholesale. Programs like Suno, which can generate a song in 10 seconds, render intentional human production nearly obsolete within its framework. AI can then produce a generically attractive avatar out of thin air to attach to this music, which is then peddled around as the Next Big Thing, like AI-created country illusion Breaking Rust and R&B digital concoction Xania Monet. A human can ultimately push the play button and tweak some things, but the bulk is handled by code. What’s more, you knew what you were getting with all the older tech—after all, most of us can identify a synthesized chord and digitally corrected pitch with practiced ease. Meanwhile, a poll conducted by French-based streaming platform Deezer revealed that out of 9,000 participants, 97% couldn’t accurately distinguish AI-generated music from human-created music. There’s zero mystery as to how we arrived at the “I Run” conundrum.

As the floodgates remain ajar for all this, we can’t exactly assume that today’s artists—legends, in some cases—will act as gatekeepers against the onslaught. Veteran producer Timbaland, for instance, launched AI entertainment company Stage Zero, powered by Suno AI, in an attempt to pioneer a new genre called “A-Pop,” or Artificial Pop. His first artist, TaTa Tekumi, debuted with a music video for “Glitch x Pulse,” a sparsely produced talk-rap stitched with a generic R&B tune, both devoid of any memorable bars or soul. The unified panning of Tata and her paint-by-numbers rap along with the backlash against Timbaland’s pro-AI advocacy seem to be the only things preventing this project from becoming relevant, seemingly confirming the notion that overtly bad AI is somewhat less threatening.

But when the machine produces an ostensibly digestible product, that’s when things get frightening. For Breaking Rust, who recently topped Billboard’s Country Digital Song Sales chart with a track called “Walk My Walk,” and Xania Monet, who became the first AI singer to debut on a Billboard radio chart after reportedly securing a multimillion-dollar record deal, their success isn’t hypothetical. Their architects are actually thriving in ways real hustling artists could only dream of.

The music industry as a whole isn’t exactly making it hard for digital interlopers to create inroads. Between massive long-delayed projects from popular mainstream artists and the pricey greed of live entertainment conglomerates rendering concerts at any scale nearly inaccessible (and yes, this includes your small local venues, many of which aren’t making enough revenue to host tours as often anymore), the patience of fans has been stretched to the limit. This creates a vacuum, and AI is more than happy to fill it. When listeners are starved for new material and priced out of experiencing their favorites live, a constant stream of algorithmically generated content starts to look less like an existential threat and more like a pressure valve. The slop becomes functional. It scratches an itch. And the industry powers that be, more aligned with consumption than creativity, take note.

This is where the year’s dominant conversation, art versus commerce, finds its most unsettling expression. We’ve spent 2025 debating authenticity across every corner of the industry: Whether streaming metrics have hollowed out what it means to have a hit (we saw this subject take early root during the Kendrick v. Drake beef, where Kendrick’s lyricism was stacked against Drake’s commercial success), if festival lineups prioritize nostalgia over discovery, or if the major label machine can still nurture genuine talent or merely exploit Gen Z’s proclivity to discover music via social media and just dish out whatever TikTok serves up. AI music, however, renders that debate almost quaint. At least the old arguments assumed a human being stood at the center of the transaction. Now we’re haggling over whether the transaction needs a human at all.

For now, sections of the industry seem to be adjusting to this new reality. In a survey featuring prominent music licensers, 97% demanded full transparency when it comes to identifying music containing elements of AI. Yet, only 49% are refusing to license AI-made music, regardless of labeling. During a recent press conference for Spotify Wrapped, the platform—which, quite notably, has used AI for its personalized DJ function and certain elements of the past two Wrapped cycles— confirmed that it would ban “bad actors” using AI to impersonate or deepfake artists’ voices, but would still “follow the artists’ lead” when it comes to how AI is used. The most alarming concept emerging from all this is “Human Premium,” or the idea that more listeners are willing to pay a premium for a platform that guarantees to offer human-only content.

But all isn’t lost. iHeartMedia recently issued a ban on all AI-generated on-air talent, music, and synthetic voices across its stations and podcasts (while admittedly still using AI for operational purposes). Jorja Smith’s record label, FAMM, is also seeking compensation from HAVEN. (who recently rerecorded their hit track with an actual human vocalist, Kaitlin Aragon) over the alleged use of her voice to train its program. And we as listeners always have the option of doing some extra detective work and confirming a song’s origins before we fall head over heels. Is the idea of doing a deep dive during every moment of discovery an exhausting thought? Absolutely. But better to know for certain what you’re falling for than to find out your favorite new artist is just Suno in a trench coat.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)