For most of the history of television, the barrier to syndication—and to profitability—has been 100 episodes. The shows that have made it to that mark are an unusual group. Many were big hits. Some found small cult audiences. Still others just hung on as best they could and never posted numbers quite low enough to be canceled. In 100 Episodes, we examine the shows that made it to that number, considering both how they advanced and reflected the medium and what contributed to their popularity. In this edition, Malcolm In The Middle, which ran for seven seasons and 151 episodes between 2000 and 2006.

In the early days of The Simpsons, the show’s writers made a concerted effort to keep stories anchored in Homer and Marge’s lower socioeconomic status. Particularly because it was a cartoon, it was important that the family have some limitations and not immediately shoot off into the stratosphere. Though this restraint obviously didn’t last, it helped make the Simpson clan initially relatable and showed how The Simpsons could appeal to both children and adults.

Fellow Fox sitcom Malcolm In The Middle shares a lot of characteristics with The Simpsons. It’s about a lower-middle-class family with three children at home (the eldest a trouble-maker, the middle brilliant), a childlike and emotional father, and a mother who has to take on the role of authority figure. While it’s live action, it also has a cartoonish sensibility: comedic set pieces, throwaway gags, and crazy situations are often around the corner. Yet for all that wackiness, Malcolm and The Simpsons have another important trait in common: Both are grounded in a family that feels real. This dynamic of overblown storytelling and human character proved remarkably durable for Malcolm In The Middle and allowed the show to keep rolling along for 151 episodes.

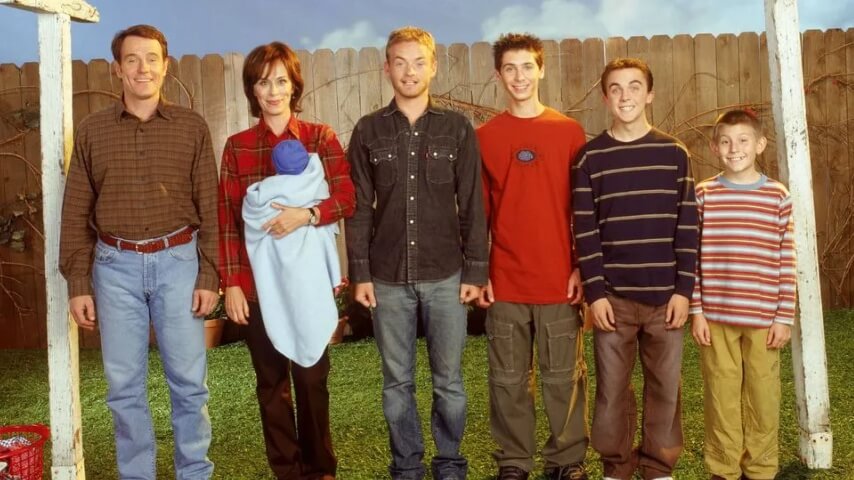

Malcolm In The Middle follows the Wilkersons (although their surname is never spoken aloud in the course of the series), an outlandish family of six, and later seven. Francis (Christopher Masterson), the eldest, is away from home—first at military school, then onto a succession of jobs. Reese (Justin Berfield) is an impulsive dummy, prone to violence, panic, and occasional flights of fancy. Frankie Muniz plays the eponymous middle child, his genius IQ at odds with his teenaged social intelligence. The youngest, Dewey (Erik Per Sullivan), is a blithe oddball, inhabiting a world borne of overactive imagination and lack of parental attention. Heading up the family are skittish Hal (Bryan Cranston) and domineering Lois (Jane Kaczmarek). Unlike most sitcoms at the time, Malcolm In The Middle was filmed in the now-ubiquitous single camera style—allowing for more intense and uncomfortably funny moments without the relief of a laugh track.

That unpolished, warts-and-all approach goes beyond filming style. It’s clear from the earliest moments of the series. “The best part about childhood,” Malcolm says in the cold open of the pilot, “is it ends.” Far from the wistful nostalgia of The Wonder Years or the chummy bickering of Home Improvement, Malcolm In The Middle presents a childhood that basically sucks. Bullies rule the school, teachers are indifferent, and being smart is akin to being radioactive.

Actually, it’s not just childhood that’s rough. As the series’ jaunty theme song—recorded by cult heroes They Might Be Giants—states, “life is unfair.” This is a philosophy that Malcolm fully embraces and it lends the series an unexpected pathos. We see it in Hal and Lois’ increasing destitution, we see it in rewards for bad behavior and punishment for trying to do the right thing, we see it in small throwaway details like the pin Lois wears on the job at the Lucky Aide drug store: “The ‘L’ stands for Value.” As Malcolm In The Middle demonstrates, the world is confusing and nonsensical, but you still have to follow along.

Life is particularly unfair for the central family. Lois sends the kids off to school, saying, “I ran out of ham, one of you’s going to have to have egg salad.” When she plans their lunch for the next day, “two of you can have slices of pizza for lunch, and the other can have… I don’t know, I think they’re peas.” Nobody is appreciated, nobody can catch a break, and everybody is upset. Yet though family members are often pitted against each other, no one is ever portrayed as a villain—except maybe for Lois’ mom, played by Cloris Leachman. Life is a struggle, so everyone is understandably grabbing on as tightly as they possibly can. A particularly poignant cold open illustrates the show’s empathy: “I wish we were old enough to drive, then we’d never be bored,” mopes Reese in his room. “I wish I could get out on my own, make a bunch of money, and start the party,” mopes Francis at school. “I wish I was a bird,” mopes Hal at work.

This understanding helps explain Malcolm In The Middle’s multi-generational appeal. As a kid, it’s possible to see it as a show about some rambunctious children trying to escape the grasp of overbearing parents. As an adult, it looks like the story of two parents trying desperately to control a brood of monsters. Both views are simultaneously valid: Malcolm knows what it’s like to be young, desperate for independence and disappointed by rules, and grownup, desperate for stability and disappointed by life.

This robust dynamic, of course, wouldn’t work without a killer cast, which Malcolm certainly had. While child actors are often unrealistically precocious or twee, Muniz, Sullivan, and Berfield play overblown but authentic kids, and Masterson successfully mixes the authority and aloofness of an eldest brother. The supporting cast is likewise excellent, with hilarious turns by David Anthony Higgins as a Lucky Aide employee in love with Lois, Craig Lamar Traylor as the sharp but slow-talking Stevie, and Gary Anthony Williams as Stevie’s gregarious dad Abe.

But Hal and Lois are the true strength of the series. Cranston’s performance as the family patriarch is captivating and hilarious. He’s a frightened child, quick to cower and squirm his way out of difficult situations. He is also the family member most likely to get involved in some insane sight gag: Cranston is a gifted physical comedian, which the writers capitalized on by having him get covered in bees, befriend a bunch of body builders, and skate magnificently to “We Are The Champions.” This characterization is particularly impressive when compared to Cranston’s career-defining turn as Walter White on Breaking Bad, a lower-middle-class father who is Hal’s polar opposite.

Kaczmarek, meanwhile, plays Lois with complete control, breathtaking in her passion and terrible in her anger. Her emotion over her children’s extreme misbehavior gives the character an almost operatic intensity, but one that never feels undeserved or inauthentic. The performance earned Kaczmarek seven consecutive Emmy nominations—one for every year Malcolm was on the air—but she never took home the award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series.

As Malcolm In The Middle aged, the seams began to show. The series maintained its energy for a long time by adding another child, fleshing out its supporting cast, and exploring new territory for its main characters—Malcolm gets a job, Reese joins the army, Dewey starts smoking cigarettes. More and more, though, there’s an overreliance on goofiness at the expense of story, giving some later episodes a scattershot, unfocused feeling. As often happens with long-running shows, Malcolm eventually outlasted its characters’ capacity for growth. Nowhere is this clearer or more disheartening than in the case of Francis. Removed from the rest of the family, Francis’ stories were often a delightful counterpoint to an episode’s main plotline. Through the course of military school and assorted odd jobs, he makes mistakes, gets in trouble, but ultimately learns, emerging as a real leader. Then, the show seems to run out of ideas for him. He’s fired for incompetence, he stays unemployed, he sort of becomes an alcoholic in one particularly cringe-worthy episode, and eventually he just sort of disappears for long stretches. It’s frustrating to have so much of a character’s growth undone for the sake of a few gags.

The disappointment with Francis’ eventual arc suggests how much the show got right. At its best, Malcolm In The Middle was ugly, unfair, and thoroughly lovable. Though the central clan might be annoying and embarrassing, they are a good family: They have an indefatigable optimism, a sense that with hard work and the right attitude, things will get better. It’s a particularly American outlook, which helps explain the series finale’s unexpected grandiosity.

On their way to hear Malcolm’s valedictorian speech, a tank full of the biggest mess Reese could concoct accidentally explodes in the car. Covered in shit (and glue and rotten eggs and dead skunk), Malcolm yells at his mother for making him choose Harvard over a lucrative tech job. Also covered in shit, she informs him that taking the easy money isn’t his path—his path is to become president of the United States. Incredulous, Malcolm asks what his policies are supposed to be.

That doesn’t matter. What does matter is you’ll be the only person in that position who will ever give a crap about people like us. We’ve been getting the short end of the stick for thousands of years, and I, for one, am sick of it. Now, you are going to be president, mister, and that’s the end of it… You know what it’s like to be poor, and you know what it’s like to work hard. Now you’re going to learn what it’s like to sweep floors and bust your ass and accomplish twice as much as all the kids around you. And it won’t mean anything because they will still look down on you. And you will want so much for them to like you, and they just won’t. And it’ll break your heart, and that’ll make your heart bigger and open your eyes and finally you will realize that there’s more to life than proving you’re the smartest person in the world.

Kaczmarek nails these speeches, with equal parts force and tenderness. The message is clear: Malcolm doesn’t get the easy path (that’s Dewey’s destiny), but his suffering will make him a greater man than he ever could have been otherwise. Life is unfair, but with tenacity, guidance, and love, you can beat the odds.