Primer: The highbrow genre fiction of Michael Chabon

The Pulitzer winner has made a career of balancing literature and pulp across a surprising number of venues.

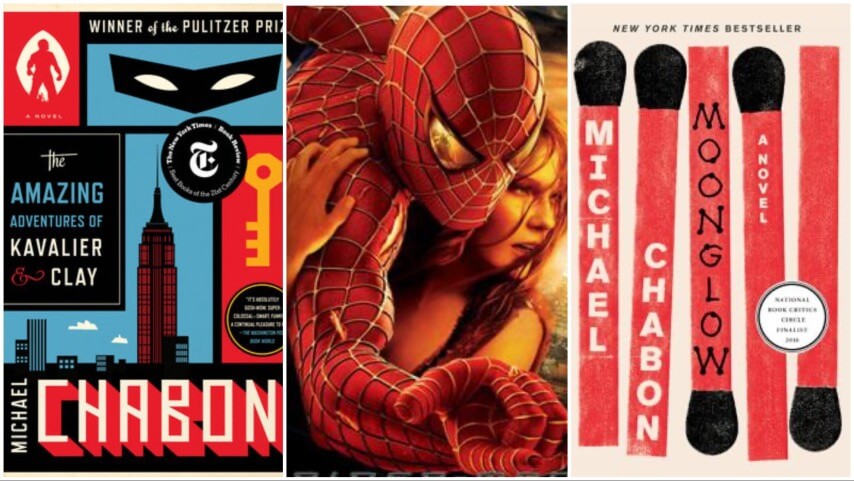

Left to right: The Amazing Adventures Of Kavalier & Clay book cover (Image: Random House); Spider-Man 2 key art (Image: Sony); Moonglow book cover (Image: Harper)

Primer is The A.V. Club‘s ongoing series of beginners’ guides to pop culture’s most notable subjects: filmmakers, music styles, literary genres, and whatever else interests us—and hopefully you.

Michael Chabon started out as a failed writer. In 1994 he was six years past his first novel, moderately well-received coming-of-age story The Mysteries Of Pittsburgh, and was nowhere close to producing a second. He had spent five years writing Fountain City, a 1,500-page epic about an architecturally perfect baseball stadium, (The Great American Novel, Chabon reasoned, would have to include baseball), which he could never quite manage to finish. His career only started in earnest when Chabon abandoned Fountain in frustration, and decided to write a book about a writer who couldn’t finish his book. Seven months later, he had finished Wonder Boys, about a college professor toiling away at an endless manuscript, and the brilliant, disaffected student he mentors through a series of mishaps.

That conceit—writing about writers, and telling stories about storytelling—unlocked Chabon’s literary voice, and swiftly led him to acclaim as one of his generation’s greatest novelists. Except calling him a novelist is a gross oversimplification. Chabon has written everything from comic books to movies to pop songs, while also writing highbrow literary fiction about everything from comic books to movies to pop songs. He’s long been interested in the intersection of pulpy genre material and literary art, but while his best work is self-consciously about writing and genre, none of it feels like too-clever meta commentary because it’s all grounded in messy, relatable characters.

It might seem too obvious to start with the big books and work your way down, but sometimes the obvious approach is the correct one. Chabon’s novels are his best and most important work; everything else is some degree of interesting and entertaining, but doesn’t quite have the same depth.

Chabon 101: Writing About Writing

The pinnacle of Chabon’s career was the year 2000, when he published bestselling, Pulitzer-winning The Adventures Of Kavalier & Clay, seven months after Curtis Hanson’s delightful film adaptation of Wonder Boys hit theaters. Wonder Boys is about the joys and frustrations of being a creative person, but more than that, it’s about the enduring literary figure of the charming fuckup. Grady Tripp, the college professor with the unfinished manuscript, is a burnout who’s constantly drunk or stoned, is having an affair with his boss’ wife, is on the outs with his own wife, and at every turn makes wrong decisions that dig him deeper into whatever hole he’s in. Tripp’s self-absorbed, unreliable, and would be an exasperating person in real life, but in Chabon’s hands he’s very easy to root for. Who among us doesn’t have big ideas we can’t bring ourselves to follow through on, and problems we’d much rather avoid?

Kavalier & Clay approaches frustrated writers from an entirely different angle, as Chabon introduces two more of his favorite themes: pulp genres and Jewish identity. Two teenage cousins, Czech refugee Josef Kavalier and Brooklyn-born Sammy Klayman, team up to create a superhero comic in 1939. Their creation, The Escapist, is an amalgamation of Jewish heroes: Harry Houdini, Superman, and Captain America (the latter two were each created by a pair of Jews as an empowerment fantasy during the rise of Adolf Hitler; in the world of the book it’s The Escapist, not Cap, who punches out der Führer on the cover of a comic book.)

The book is several kinds of enthralling story at once. It’s a snapshot of a pivotal time and place in history; it’s the story of a fruitful creative partnership; it’s a story about an immigrant assimilating (Joe) and a young gay man in an era where no world outside the closet exists (Sammy). But most of all it’s about the complicated relationships between chummy, eager-to-please, but perpetually fearful Sammy, aloof, artistically ambitious, but perpetually angry Joe, and Rosa Saks, the alluring bohemian who bonds with both men in different ways. The book received universal acclaim upon its release; if you’re only going to read one Chabon novel, this is the one.

Chabon revisits pop culture and complicated relationships from an entirely different angle in Telegraph Avenue (2012). The story centers on the friendship between two families, one Jewish, one Black. The husbands co-own a record store in Brokeland, their name for the Oakland-Berkeley borderlands, whose rapid gentrification is threatening to drive them out of business. The wives work together as midwives, and their own business is threatened when they react with justifiable anger at a doctor’s racism. While Chabon is always concerned with identity, exploring racial identity other than his own is new ground, and he handles it deftly here, largely by keeping his characters as complicated and grounded in everyday concerns as in his other work. He also makes room for musings on music, film, fame, money, and the importance of small cultural institutions like the local record store. The book isn’t perfect—a chapter from the point of view of an up-and-coming politician named Barack Obama (the book is set in 2004) is aggressively unnecessary—but Chabon makes Brokeland a world you want to spend more time in (and protect from gentrification’s endless reach).

Chabon has also put his own twist on the memoir. Moonglow (2016) is a fictionalized memoir of his grandfather’s life (how fictionalized is deliberately ambiguous), which manages to be both intensely personal and a sweeping overview of America in the second half of the 20th century. The story jumps around in time, through World War II, marriage to a French Jewish refugee, a stint in jail, and a career as an engineer. His grandfather tells him at some point, “Put the whole thing in chronological order, not like this mishmash I’m making you.” But the mishmash is the whole point. Somehow, exploring a life in fractured moments gives a fuller picture than a straightforward recounting of events.